“See at Your Feet a Suppliant One” As Sung By Miss Ella Wren, In Balfe’s Grand Opera of the Bohemian Girl. An example of Confederate sheet music

Music has always played a powerful role in cultures around the world. Now sheet music provides a glimpse at people’s daily lives and illustrates changes in fashion, dress, and even behavioral expectations. Collecting sheet music isn’t just for music lovers; it’s an engaging pursuit that frequently intersects with history and literature.

The first music to appear in a printed volume was in the Codex spalmorum (1457). But the work didn’t include the actual notes; instead the text was printed with blank space to manually add the music to each manuscript! It wasn’t until 1473, with the publication of the Constance gradual in Germany, that music appeared fully printed. Three years later, Ulrich Hahn published Missale secundum consuetudinem curie romane, which included music printed with woodcuts. He claimed to be the first to print music, but most experts agree the Constance gradual was the true first. Soon after, missals, graduals, and other religious texts began popping up all over Europe, and many contained printed music.

The difficulty with printing music is that it generally requires multiple print runs: one to print the staff lines, and another to print the actual notes and notations. Hahn and his successors got around this issue by using woodcuts. Eventually, however, new printing technologies–namely moveable type and lithography–were adopted for music as well. (Famous revolutionary and publisher Isaiah Thomas was the first to use moveable type to print music in the United States. More on him later this month!)

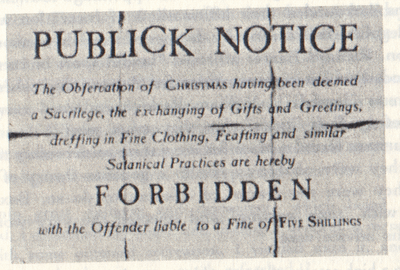

Illustrations and themes of antiquarian sheet music can be an uncomfortable reminder of the past. This item, from the Bohemian Club, is quite rare with none listed in OCLC.

By the 1820’s, however, the most common method for printing music was engraved plates. This has produced numerous bibliographic obstacles for collectors and scholars today. First, not all sheet music bore copyright information in the first place. Next, publishers would often store the plates for long periods of time and simply use them, unaltered, for later reprints whenever they needed to replenish their stock. And sometimes they sold these plates to other publishers, who didn’t bother emending copyright information when it did exist. Sometimes the plate numbers can be used to determine an approximate date, but that’s largely based on how much is known about the particular engraver or publisher. Collectors of nineteenth-century sheet music, then, must put their detective skills to the test on a regular basis–and be comfortable with some uncertainty about publication information.

While many antiquarian book collectors would shy away from works that are not definitive first editions, this factor is less important with sheet music. These items were printed with the intention of being ephemera, and of being used. They often bear the marks of use, such as tears, smudges, wear, and mending with tape or sewing thread. Music printed in the early nineteenth century and earlier tends to be more durable than later sheet music because it was printed on paper made of rag rather than wood pulp. Meanwhile, during the heyday of American sheet music, it was common to print sheet music as newspaper supplements. These items, printed on thin, cheap paper, are often quite fragile if they survived at all. Collectors must be quite mindful of preservation issues to extend the longevity of their sheet music.

Highlights from Our Sheet Music Collection

A Complete Dictionary of Music

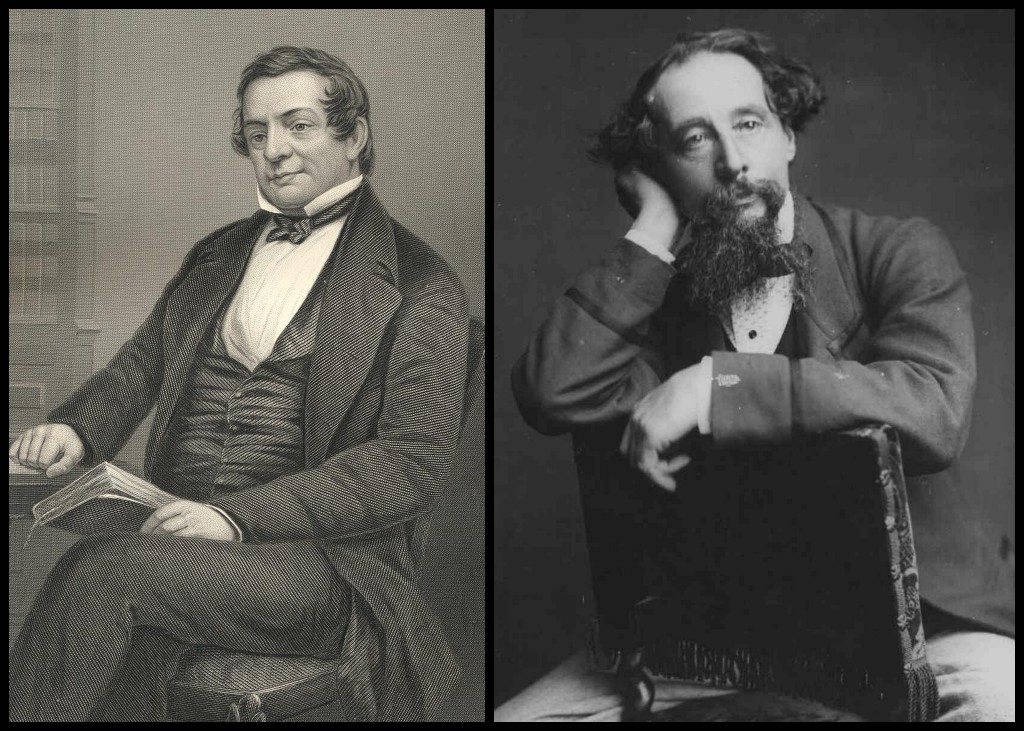

Thomas Busby, author of A Complete Dictionary of Music, began his musical career at a young age. After being rejected as too old to be a chorister by Westminster Abbey organist Benjamin Cooke, he went on to study under Samuel Champness, Charles Knyvett, and Jonathan Battishill. Busby’s first musical venture was music to accompany William Kenrick’s play The Man the Master. This remained incomplete during his lifetime. His next pursuit, an oratorio for Alexander Pope’s Messiah, occupied Busby intermittently for several years. He published a musical dictionary with Samuel Arnold in 1786, along with a serial called The Divine Harmonist. Busby also published the first music periodical in England, The Monthly Musical Journal. His A Complete Dictionary of Music went through several editions during his lifetime.

Thomas Busby, author of A Complete Dictionary of Music, began his musical career at a young age. After being rejected as too old to be a chorister by Westminster Abbey organist Benjamin Cooke, he went on to study under Samuel Champness, Charles Knyvett, and Jonathan Battishill. Busby’s first musical venture was music to accompany William Kenrick’s play The Man the Master. This remained incomplete during his lifetime. His next pursuit, an oratorio for Alexander Pope’s Messiah, occupied Busby intermittently for several years. He published a musical dictionary with Samuel Arnold in 1786, along with a serial called The Divine Harmonist. Busby also published the first music periodical in England, The Monthly Musical Journal. His A Complete Dictionary of Music went through several editions during his lifetime.

A Sheet Music Sammelband

Occasionally also called a nonce-volume, a sammelband is a collection of works that were originally published separately and have since been bound together. A musician or music enthusiast might assemble a sammelband of favorite pieces, while music teachers might put them together to teach students specific skills in a set progression. This particular sammelband contains 43 pieces, ranging from waltzes and quadrilles to country dances, sonatas, and operas. It includes a handwritten “Contents” at the front. Much of the music was composed for the piano forte, so the original owner likely played this delightful instrument.

Occasionally also called a nonce-volume, a sammelband is a collection of works that were originally published separately and have since been bound together. A musician or music enthusiast might assemble a sammelband of favorite pieces, while music teachers might put them together to teach students specific skills in a set progression. This particular sammelband contains 43 pieces, ranging from waltzes and quadrilles to country dances, sonatas, and operas. It includes a handwritten “Contents” at the front. Much of the music was composed for the piano forte, so the original owner likely played this delightful instrument.

“Carrie Bell”

Captain WC Capers, who wrote the words to “Carrie Bell,” was formerly of the “Macon Volunteers” and had served in the Florida Indian Wars (1836). During the Civil War, he commanded Company G, 1st LA Heavy Artillery Regiment of the CSA. In July 1863, Capers was promoted to Major. He saw service at Vicksburg and elsewhere in the South. Confederate sheet music such as “Carrie Bell” was much more frequently published via lithography instead of engraved plates because metal was such an important commodity during the war–it simply wasn’t available for making engraved plates.

Captain WC Capers, who wrote the words to “Carrie Bell,” was formerly of the “Macon Volunteers” and had served in the Florida Indian Wars (1836). During the Civil War, he commanded Company G, 1st LA Heavy Artillery Regiment of the CSA. In July 1863, Capers was promoted to Major. He saw service at Vicksburg and elsewhere in the South. Confederate sheet music such as “Carrie Bell” was much more frequently published via lithography instead of engraved plates because metal was such an important commodity during the war–it simply wasn’t available for making engraved plates.

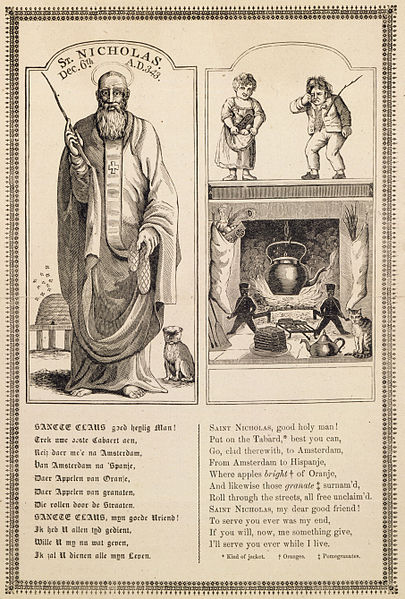

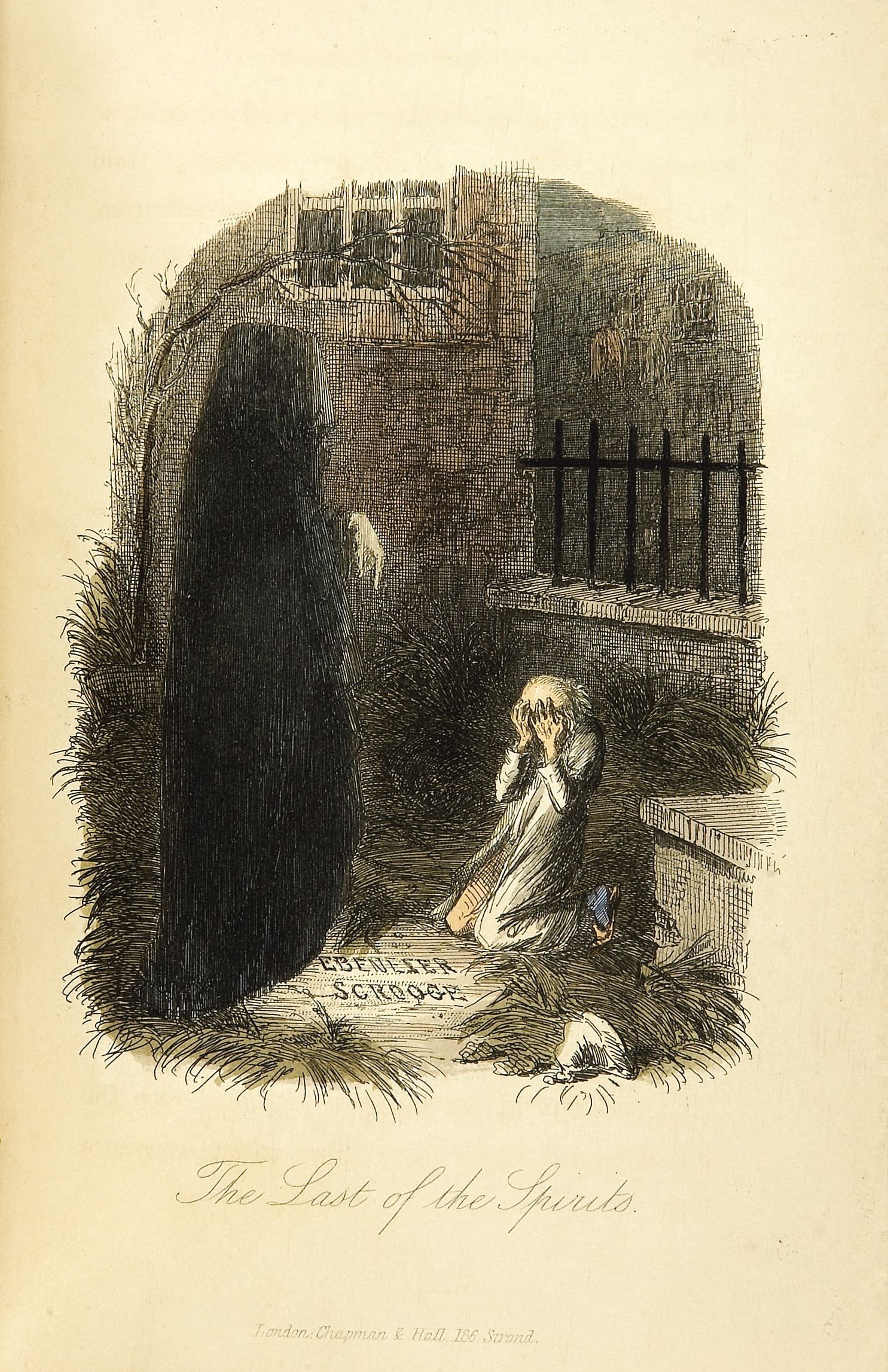

“The Ivy Green”

Though “The Ivy Green” makes its first appearance in Chapter Six of The Pickwick Papers, Kitton informs us that the piece wasn’t written expressly for the novel. The favorite setting for the piece was by veteran Henry Russell, who said he received the whopping sum of ten shillings for the composition. Dickens frequently incorporated popular music into his works. He also occasionally wrote his own pieces, such as the satirical ballad “The Fine Old English Gentlemen,” which he penned for The Examiner and said should be sung at all conservative dinners. Meanwhile, Dickens’ extraordinary popularity meant that his novels often took on lives of their own, and people also composed their own musical pieces based on Dickens’ works.

Though “The Ivy Green” makes its first appearance in Chapter Six of The Pickwick Papers, Kitton informs us that the piece wasn’t written expressly for the novel. The favorite setting for the piece was by veteran Henry Russell, who said he received the whopping sum of ten shillings for the composition. Dickens frequently incorporated popular music into his works. He also occasionally wrote his own pieces, such as the satirical ballad “The Fine Old English Gentlemen,” which he penned for The Examiner and said should be sung at all conservative dinners. Meanwhile, Dickens’ extraordinary popularity meant that his novels often took on lives of their own, and people also composed their own musical pieces based on Dickens’ works.