Surely Charles Dickens took many secrets to his grave, but one of those secrets didn’t last long. Dickens made a significant change to the ending of Great Expectations–and in the nick of time! He’d already sent his manuscript off to the publisher when he decided on the change. Dickens’ indecision means that collectors have a few different editions of this great novel to add to their personal libraries.

A Considerable Emendation

It was relatively common for authors to change their work, sometimes even between printings. Henry James, for instance, was notorious for updating his drafts multiple times. So Dickens’ last-minute emendation to Great Expectations isn’t entirely unheard of–he, like James, actually made such changes with relative frequency.

However, Dickens had also originally promised that Great Expectations would be lighter fare than its predecessor, Tale of Two Cities. In an October 1860 letter to John Forster, Dickens wrote “You will not have to complain of the want of humor as in Tale of Two Cities. I have made the opening, I hope, in its general effect exceedingly droll.”* The novel took a different turn, and Dickens’ original ending was melancholy indeed.

“I was in England again–in London, and walking along Piccadilly with Little Pip–when a servant came running after me to ask would I step back to a lady in a carriage who wished to speak to me. It was a little pony carriage, which the lady was driving; and the lady and I looked sadly enough on one another.

‘I am greatly changed, I know, but I thought you would like to shake hands with Estella too, Pip. Lift up that pretty child and let me kiss it!’ (She supposed the child, I think, to be my child.)

I was very glad afterwards to have had the interview; for, in her face and in her voice, and in her touch, she gave me the assurance, that suffering had been stronger than Miss Havisham’s teaching, and had given her a heart to understand what my heart used to be.”

Dickens submitted Great Expectations with this ending in 1861 and went to visit his friend and fellow author Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Lytton was a popular figure in his own right as a writer of crime historical and crime novels. He was also a man of privilege, and it’s likely that Dickens respected Lytton as both an author and as a gentleman. Probably on these grounds, Dickens shared the Great Expectations manuscript with Lytton.

He may have been surprised with Lytton’s reaction. Rather than wholeheartedly praising Dickens’ latest novel, Lytton urged Dickens to rewrite the ending completely. Dickens intimated that “Bulwer was so very anxious that I should alter the end…and stated his reasons so well, that I have resumed the wheel, and taken another turn at it.” What Dickens came up with has been the standard ending since 1862:

“‘I little thought,’ said Estella, ‘that I should take leave of you in taking leave of this spot. I am very glad to do so.’

‘Glad to part again, Estella? To me, parting is a painful thing. To me, the remembrance of our last meeting has been ever mournful and painful.’

‘But you said to me,’ returned Estella, very earnestly, ‘”God bless you, God forgive you!'”And if you could say that to me then, you will not hesitate to say that to me now–now, when suffering has been stronger than all other teaching, and has taught me to understand what your heart used to be. I have been bent and broken, but–I hope–into a better shape. Be as considerate and good to me as you were, and tell me we are friends.’

‘We are friends,’ said I, rising and bending over her, as she rose from the bench.

‘And will continue friends apart,’ said Estella.

I took her hand in mine, and we went out of the ruined place; and, as the morning mists had risen long ago when I first left the forge, so the evening mists were rising now, and in all the broad expanse of tranquil light they showed to me, I saw no shadow of another parting from her.

In his manuscript, the final line reads “I saw the shadow of no parting from her, but one.” And the first edition offers yet another variation of that closing line: “I saw the shadow of no parting from her.” Dickens was clearly ambivalent about the novel’s ending. But his eye for the market probably led him to write an ending that can be interpreted as Estella and Pip “walking off into the sunset” together. If he’d wanted that, wouldn’t he have made the ending more obviously happy, as he did in Bleak House, Little Dorrit, and David Copperfield?

Complications for Dickens Critics and Collectors

Critics have been rehashing the endings of Great Expectations since the book was published. The dual endings also create a bit of a complication for collectors; ordinarily the first edition of a work is enough for a collector to “check something off the list.” In the case of Great Expectations, however, true Dickens collectors will want a few more items.

Because Dickens slightly changed the wording of the ending after the first edition, most collectors look for both the first edition and the 1862 edition, which was the first to include the now-ubiquitous ending. Forster’s biography, where the alternate ending made its first appearance in print, is also a highly desirable volume. And finally, Dickens’ original ending did not appear alongside the text of Great Expectations until 1937, when George Bernard Shaw included it in his preface for the Limited Editions publication of the novel.

This is one example of an instance where collectors would seek both a first edition and subsequent editions for a complete collection of an author’s oeuvre. It also shows us the value of basic bibliographic resources that can identify and elucidate these kinds of circumstances, along with working with an expert professional bookseller who can guide your collecting efforts.

*This letter is apparently not currently extant, though we know of it through Forster’s Life of Dickens (vol 3, p 329).

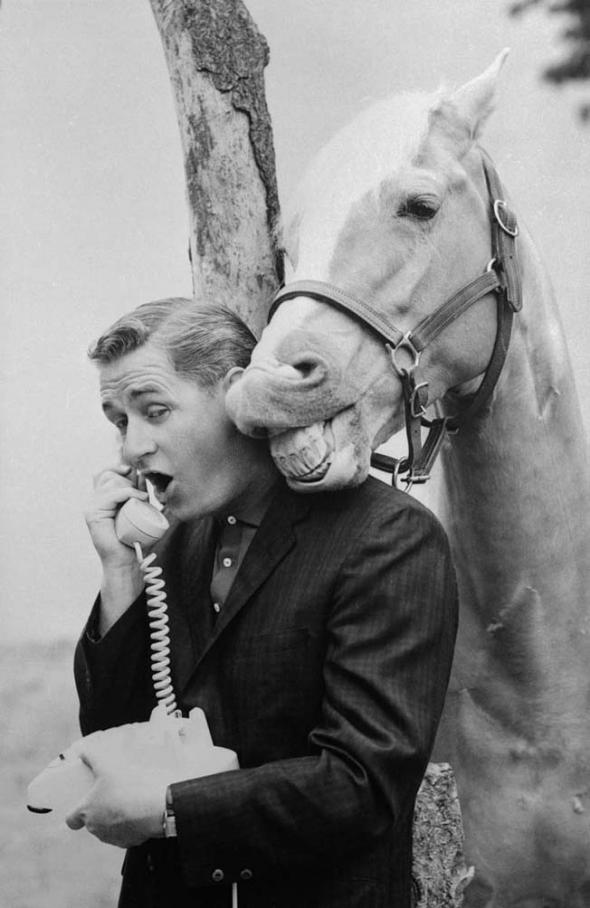

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.”

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.” The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.

The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.