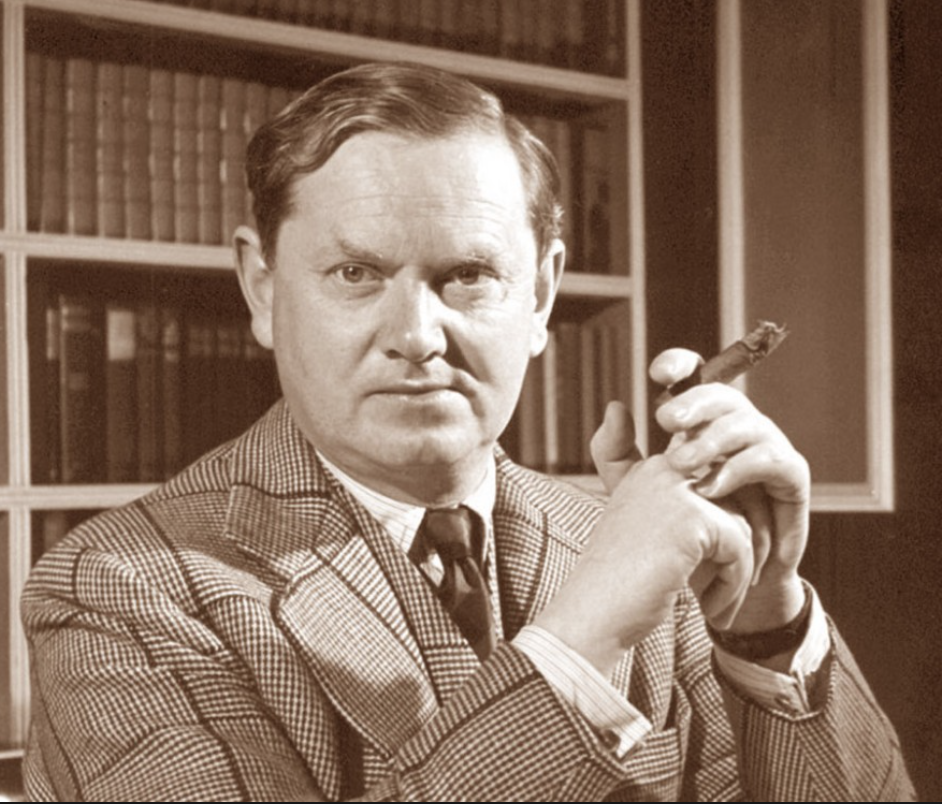

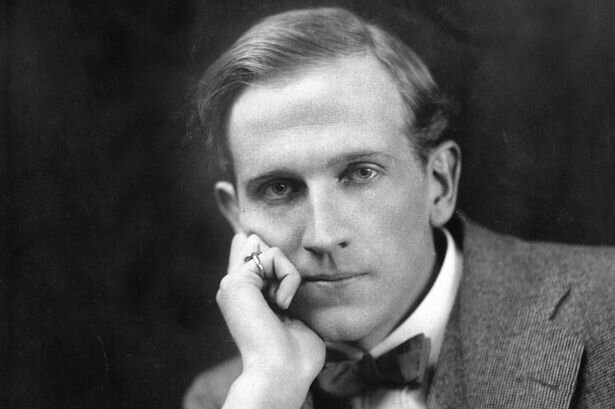

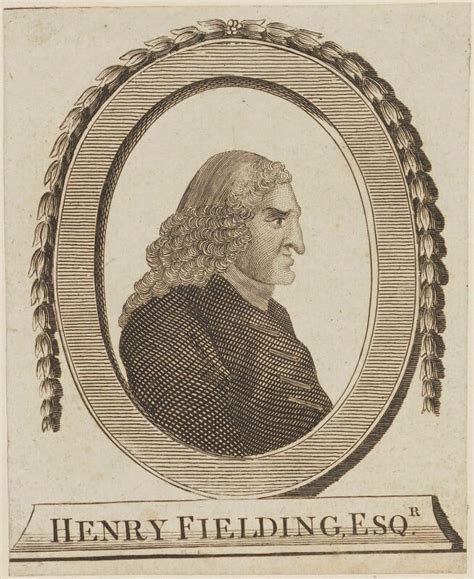

On October 8th, we remember Henry Fielding, author extraordinaire and one of the masters of the novel as we know it. Born in 1707, Fielding began his career as a playwright before turning to writing prose when the stage was temporarily closed to political satire from government censorship. His understanding of human nature, combined with his keen sense of humor and (many) moral observations soon found a perfect outlet in the world of fiction. Twists of fate led him to produce one of the most influential novels of the 18th century and the one that would make him famous – The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling.

*

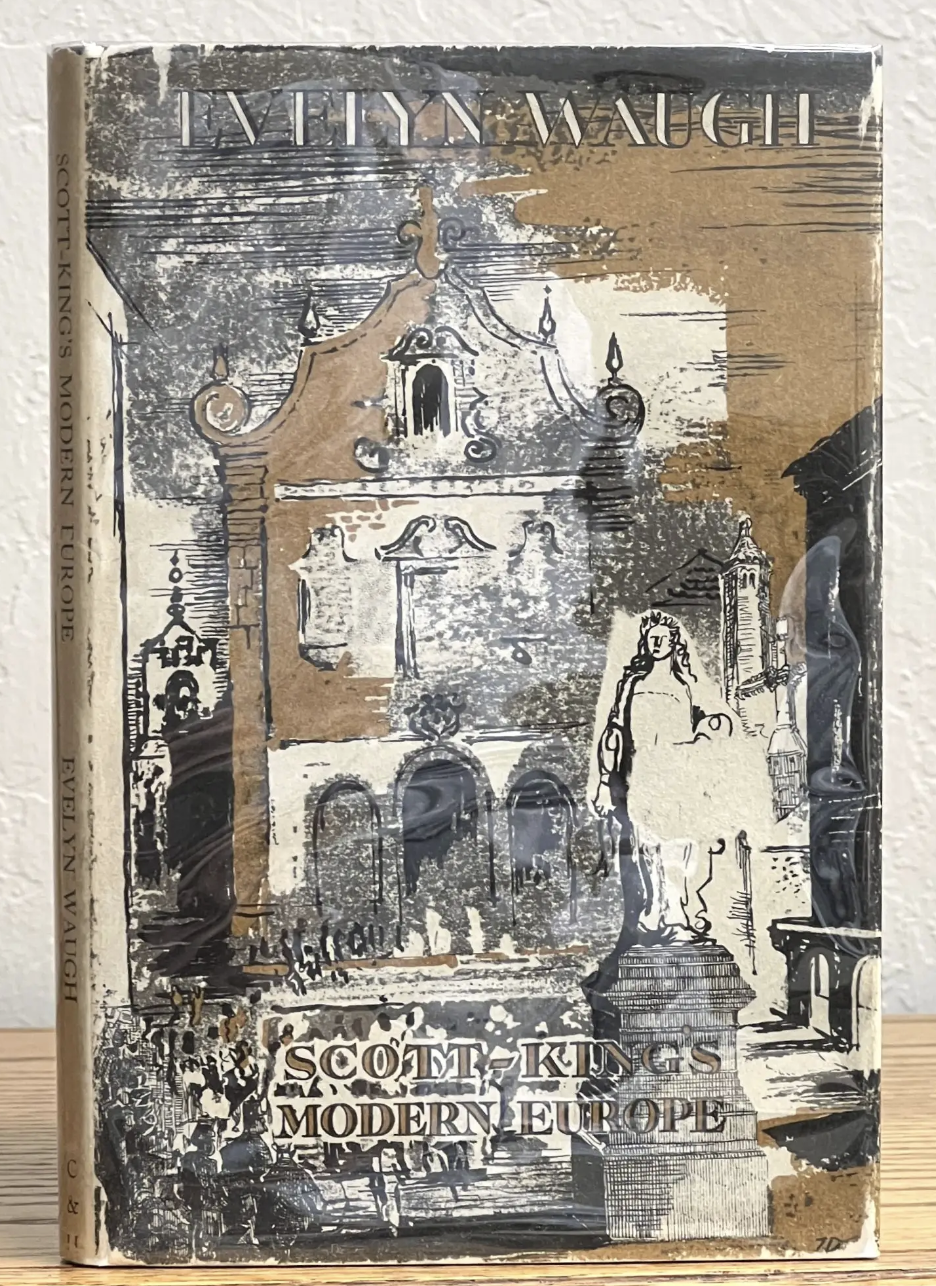

Published in 1749, The History of Tom Jones follows the imperfect hero Tom, an orphan raised by the kind Squire Allworthy, whose good heart often lands him in trouble. Tom’s adventures (or misadventures, some might call them) take him through a series of comedic and romantic entanglements throughout London and the countryside… complete with duels, misunderstandings and mistaken identities as he struggles to prove his worth and win the heart of his beloved. Despite its quite lighthearted tone, Tom Jones explores themes of virtue and hypocrisy, and at its heart it is a rollicking story of love, morality and mischief. That being said, instead of offering us an idealized hero or purely moral tales, Fielding gave readers a hero who made mistakes, learned from them and grew. Innovative for his time! The book was an immediate success – readers simply devoured it for the wit and the scandal, while academics and scholars praised its writing style and craftsmanship.

Fielding’s inspiration for Tom Jones grew out of both his personal experiences and his observations of 18th century society. Having worked as a magistrate in London, he witnessed the realities of human behavior – both noble and corrupt – which he translated into his fiction with humor and empathy alike. Fielding proved his belief that goodness could be found even in flawed characters. Many critics often point to Tom Jones as one of the first “modern” novels, because his use of satire and irony – especially focusing on class and human folly – perhaps set the precedent for authors like Dickens and Austen to follow in his footsteps.

The History of Tom Jones was revolutionary in its form and voice, and in combining moral reflection with humor and entertainment. As we honor Henry Fielding on the anniversary of his death, we celebrate the reminder that storytelling can be both moral and mischievous, all at the same time!