“Grow old with me! The best is yet to come.” Somehow we wonder how Robert Browning might be perceived today with what some consider his dark humor and wicked social commentary. His knowledge of several Romance languages, plus a musical background seem to have been important influences on his life as a poet. As his May 7th birthday dawns, we take his interesting life (and the fact that, in much the spirit of today’s generations, he chose to stay at home until his mid-thirties marriage) and examine the lasting influence he has had on the literary world in honor of his 213th birthday!

*

Robert Browning was born in Surrey, on the 7th of May in 1812. Browning grew up with a rather literary father, and a talented musician for a mother (and we wonder how he became the writer he was!). During his most formative years, Browning had a solid learning foundation, as his father was rather firm in his expectations for his gifted son. Browning’s father housed a library of over 6,000 titles – rather remarkable for that day and age. And what a collector after our own hearts! The young Robert Browning was expected to make use of his father’s collection at every opportunity (…what a hardship!) A brief foray into a more formal environment (the University of London) proved to not be to Robert’s liking, and he returned to his home after his , and his world of books and music, until his “later” marriage in 1846. He managed to publish several works during his time at home – his “Paracelsus”, published in 1835, drew the attention of literary greats Charles Dickens, William Wordsworth and Alfred Tennyson. “Paracelsus” became Browning’s introduction to London’s literary world. From there on, his works managed to bring both praise and criticism. Browning seemed to care little for either side of the coin, however, and he turned down almost all public speaking appearances, never wavering in his wish to remain true to himself, rather than be swept up into the grand life of the London literary scene.

In 1845, Robert met poet Elizabeth Barrett (whose name may ring a bell to some of you bibliophiles), and they began a correspondence that turned into love. They secretly married in September of 1846, and it was the beginning of an entirely new chapter in Robert Browning’s work and life. It was during his marriage to Elizabeth that he wrote the bulk of his literary output – a fountain of poetry and a few plays. Browning’s marriage to Elizabeth was tantamount to them both for not only their happiness, but also their exposure. Due to Elizabeth’s father’s disinheritance upon her marrying (not because he disapproved of Robert, but because he disapproved of his children marrying in general), the Browning’s spent much of their married life living in Italy. Nevertheless, their life in Italy managed to bring its own round of criticism to the couple as they were originally branded “deserters” of England in literary circles. That being said, in today’s society Browning would be heralded for his opposition to slavery of the time and his avid support of women (as is seen by his own excitement for his wife’s success in her work).

Upon Elizabeth’s death in 1861, Browning finally returned to England with their son Robert Barrett (nicknamed “Pen”). Browning continued to publish works and was considered one of the most in-demand London literary figures. Browning’s poetry ranges from dramatic monologue (with works like “My Last Duchess” and “Far Lippo Lipa” coming to mind), to serious themes (like “Porphyria’s Lover” – a work centering on an obsession that borders between passion and madness) to a much lighter lyrical voice – “The Pied Piper of Hamlin” remains, to this day, a cherished and popular addition to children’s literature.

*

Although Browning is often identified side-by-side with his wife, he is worth examining on his own! A writer who never wavered in his beliefs, and who showed more than adequate representation of his views in his writings – declaring them both lyrically and socially – deserves to have a second look. We remember him as his birthday passes for reasons we perhaps were not originally exposed to, especially in our school classes of yesteryear. We cheers to Browning’s strength of characterization and his ahead-of-his-time beliefs – so many of which we today take for granted! Happy Birthday to Robert Browning!

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

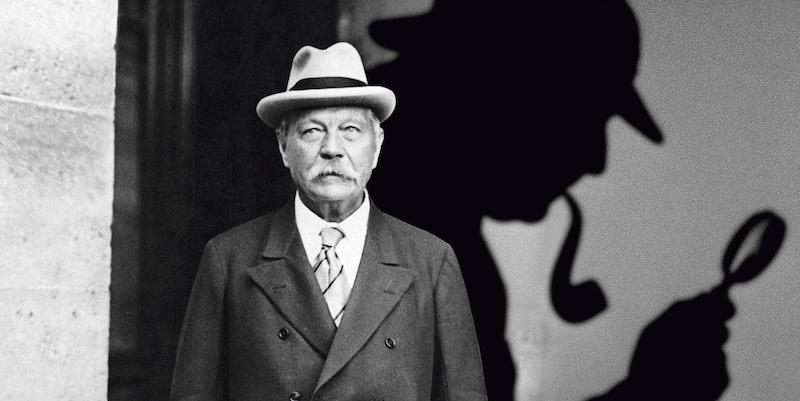

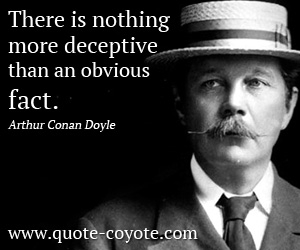

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his first Sherlock Holmes installment, A Study in Scarlet, when he was only 27 years old. Written in just under three weeks, it is amazing to think that on how this work has endured and began a legacy, a series the likes of which may be unparalleled in fiction. A Study in Scarlet was popular and successful, and Conan Doyle was commissioned to write a sequel in less than a year. The next work, The Sign of the Four, was no less popular when it appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine. Amusingly enough, even early on in his Holmes works Conan Doyle felt contradictory emotions towards his most famous character. He wished to kill Holmes off after just a couple years, but was dissuaded (more like forbade) from doing so by his own mother! He raised the prices for his stories hoping to dissuade publishers from paying for them, but found that publishers were willing to pay exorbitant sums to keep the stories coming… consequently Conan Doyle accidentally became one of the best paid authors of all time. In all, Conan Doyle featured Sherlock Holmes (often against his will – public outcry was so great after Doyle had Holmes and Moriarty plunge off a cliff together that Holmes was forced to resurrect his famed detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles years later) in fifty-six short stories and four novels – a long and eventful life for a fictional character!

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his first Sherlock Holmes installment, A Study in Scarlet, when he was only 27 years old. Written in just under three weeks, it is amazing to think that on how this work has endured and began a legacy, a series the likes of which may be unparalleled in fiction. A Study in Scarlet was popular and successful, and Conan Doyle was commissioned to write a sequel in less than a year. The next work, The Sign of the Four, was no less popular when it appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine. Amusingly enough, even early on in his Holmes works Conan Doyle felt contradictory emotions towards his most famous character. He wished to kill Holmes off after just a couple years, but was dissuaded (more like forbade) from doing so by his own mother! He raised the prices for his stories hoping to dissuade publishers from paying for them, but found that publishers were willing to pay exorbitant sums to keep the stories coming… consequently Conan Doyle accidentally became one of the best paid authors of all time. In all, Conan Doyle featured Sherlock Holmes (often against his will – public outcry was so great after Doyle had Holmes and Moriarty plunge off a cliff together that Holmes was forced to resurrect his famed detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles years later) in fifty-six short stories and four novels – a long and eventful life for a fictional character!