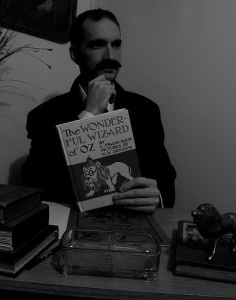

Though L Frank Baum is best known as the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the famed author had a rich and varied career. His accomplishments include trade magazines and newspapers, along with an oft-forgotten play based on his sequels to Wizard of Oz.

Early Literary Aptitude

Born on May 15, 1856, Lyman Frank Baum was a sickly child. Particularly fond of fairy tales and British authors like Charles Dickens, Baum spent much of his time reading. But Baum found fault with fairy tales because they were so often frightening and gruesome. He would later note, “One thing I never liked then…was the introduction of witches and goblins into the story. I didn’t like the little dwarfs in the woods bobbing up with their horrors.” Thus, from an early age, Baum resolved to write a different kind of fairy tale.

Born on May 15, 1856, Lyman Frank Baum was a sickly child. Particularly fond of fairy tales and British authors like Charles Dickens, Baum spent much of his time reading. But Baum found fault with fairy tales because they were so often frightening and gruesome. He would later note, “One thing I never liked then…was the introduction of witches and goblins into the story. I didn’t like the little dwarfs in the woods bobbing up with their horrors.” Thus, from an early age, Baum resolved to write a different kind of fairy tale.

But his first literary exertions weren’t fairy tales: Baum started his own newspaper, The Rose Lawn Home Journal with a printing press purchased by his father. Baum took the publication quite seriously, writing news pieces and editorials, along with poetry, word games, and fiction. The young man’s paper did quite well, and a number of local businesses purchased advertising space in its pages. In 1873, Baum launched two more papers, The Empire and The Stamp Collector.

Meanwhile it had become quite fashionable to breed chickens and other fowl. Baum took up breeding Hamburgs and won several awards with his birds. He also launched The Poultry Record, a magazine devoted to breeding and raising poultry. The publication was rather successful. Then in 1886, Baum published his first book, The Book of the Hamburgs: A Brief Treatise upon the Mating, Rearing, and Management of the Different Varieties of Hamburgs.

A Love for Theatre

Baum also found time to nurture his interest in theatre. He frequently memorized passages of Shakespeare and even founded a Shakespearean troupe with his father’s financial backing. The elder Baum had made a fortune in the family business and purchased a number of opera houses in Pennsylvania and New York. He entrusted their management to his son in 1880. Baum proved quite adept, even delving into writing his own plays. The Maid of Arran, considered Baum’s first major literary work, met with immediate success.

But with the decline of the Baum’s father’s health and two unlucky episodes with swindling employees, Baum was left virtually penniless. His wife, Maud, suggested that the family move West. They settled in Dakota territory, where Baum opened a general store called Baum’s Bazaar. Soon Baum had made a reputation for two things: storytelling and extending credit. Thanks to Baum’s generous spirit and a drought that left most of his customers destitute, the bank foreclosed on Baum’s Bazaar in 1890, only two years after it opened. Baum established The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, acting as reporter, printer, and salesman all in one. But that, too, failed in 1891.

Return to Authorship

That year, Baum decided to move his family to Chicago. The World Columbian Exposition was there, so employment opportunities were plentiful. First Baum worked as a reporter for the Evening Post, but the paltry pay was hardly enough to support a family. Next he went into sales for the china company Pitkin & Brooks. He was often on the road. His mother-in-law, noted feminist Matilda Gage, moved in to help with the Baum children. It was she who encouraged Baum to write down the fairy tales he spun for his children and their young friends.

Baum frequented the Chicago Press Club when he wasn’t traveling. It’s been conjectured that Baum met illustrator Maxfield Parrish, resulting in Mother Goose in Prose (1897). But so far as we know, the two never actually met; Chauncey Williams of Way and Williams negotiated for Parrish’s illustrations in the children’s book. Williams also served as publisher of The Show Window when the journal was launched in 1897. The magazine gave Baum an opportunity to make a living without traveling as a salesman.

A Serendipitous Acquaintance

Soon Baum made the acquaintance of William W Denslow. Though the two had disparate personalities, they decided to collaborate on a companion to Mother Goose in Prose. Together they published Father Goose, His Book in 1899. The beloved book spurred Songs of Father Goose. The pair worked on a few more project, most notably The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Baum had originally submitted the story with the title The Emerald City, which publishers Hill and Company rejected. They finally agreed on a new title, and the first edition appeared in May, 1900.

Two years later, Baum collaborated with Paul Tietjens and Julian P Mitchell on an adult musical adaptation of Wizard of Oz. A major success, the production toured all over America. The country was absolutely infatuated with the land of Oz and its whimsical characters. Baum published a total of thirteen Oz books and six short Oz stories and came to be known as the “Royal Historian of Oz.” The Ozmapolitan, a promotional piece, was issued in 1904 to help Reilly & Britton advertise The Marvelous Land of Oz, which was the new firm’s first publication. Occasional later versions of The Ozmapolitan were also issued.

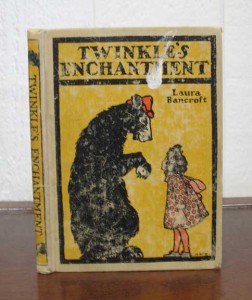

Though he indulged his audience with all these tales of Oz, he longed to delve into other projects. Baum often used pseudonyms for these endeavors, so that he didn’t have to worry about their critical reception. One notable project was Aunt Jane’s Nieces, a series for teenage girls Baum published under the pen name Edith Van Dyne. He also wrote under the names Laura Bancroft, Floyd Akres, Captain Hugh Fitzgerald, Suzanne Metcalf, and John Estes Cooke.

Though he indulged his audience with all these tales of Oz, he longed to delve into other projects. Baum often used pseudonyms for these endeavors, so that he didn’t have to worry about their critical reception. One notable project was Aunt Jane’s Nieces, a series for teenage girls Baum published under the pen name Edith Van Dyne. He also wrote under the names Laura Bancroft, Floyd Akres, Captain Hugh Fitzgerald, Suzanne Metcalf, and John Estes Cooke.

Baum also launched a traveling show called “Fairylogue and Radio Plays.” The show featured live actors costumed as characters from several of Baum’s fantasy books, a live orchestra, motion-picture clips, and colored lantern slides. Baum traveled with the show as master of ceremonies. The endeavor proved a commercial failure.

Return to the Stage

In 1913, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz made its debut on the stage. Producer Oliver Morosco inserted three songs he wrote (with music composed by Victor Schertzinger). Billed as “a companion play to The Wizard of Oz, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz met with great success in Los Angeles, but didn’t resonate with other audiences. Chicago critics were particularly unimpressed. Though the show made money, Morosco decided not to keep producing it.

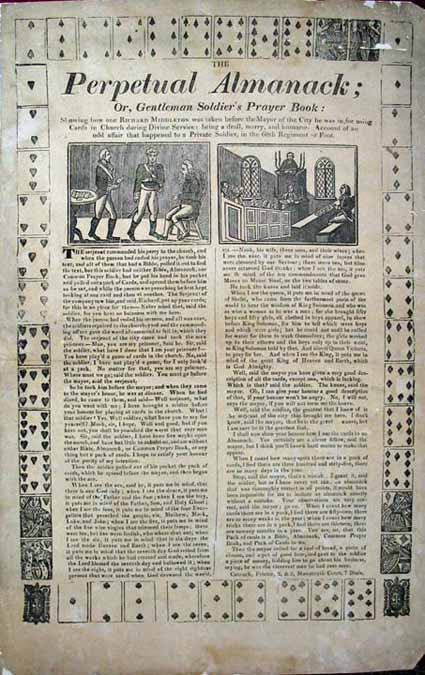

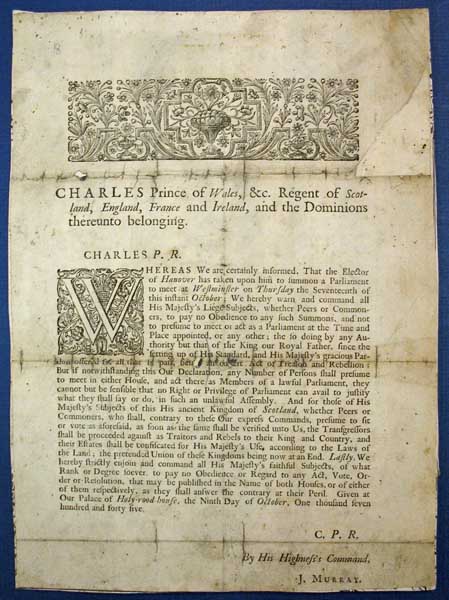

Only an early manuscript of the musical is extant, and the play probably would have faded into obscurity were it not for the published music and advertisements. Promotional materials for the production have proven exceedingly rare; a survey of auction records and other online sources indicate only two extant playbills. One, from December 2, 1913 at the Babcock Theatre in Billings, Montana, comes from the collection of Fred M Meyer and can be viewed at the International Wizard of Oz Club website. The other, from the play’s opening night in San Francisco on April 21, 1913, is pictured here. We’re proud to offer this item as one of this month’s select acquisitions, which features a diverse collection of broadsides.

We invite you to peruse the entire list! Should you have a question about any item, please feel free to contact us.

Many thanks to our esteemed friend Peter E Hanff for his contributions to this article. The Deputy Director of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, Hanff is a great scholar of L Frank Baum. He collaborated with Douglas G Greene on Bibliographia Oziana, the main bibliographic record and resource on Oz literature.