Cormac McCarthy has a devoted following of readers & collectors, and as such, this Pulitzer-Prize winning author has drawn the interest of those who prey on such collectors. My ABAA colleague, Scott Brown, in a recent blog, identifies and discusses some fake McCarthy proofs recently discovered in the market. In an effort to disseminate this bibliographic information to a wider audience in the hopes of precluding the perpetuation of any further fraud, we share this information with you.

Finally, as one of my other colleagues is known remark, “Be careful out there.”

Kind regards,

Vic

Forged proofs1 exist for many of Cormac McCarthy’s books. They have fooled major McCarthy collectors, top dealers in first editions, and specialist book auction houses. You can read how I came across these fakes in my regular Dispatch newsletter.

This list is intended to help collectors and booksellers identify fake proofs of the first editions of Cormac McCarthy’s first five novels, the ones published before the break-out success of All the Pretty Horses in 1992.

Please contact Downtown Brown Books or post a comment to this post if you have corrections or questions about this list.

The starting point for this project was an attempt to compile a list of all the proofs of Cormac McCarthy’s novels known to exist before the forged proofs began to appear in the 2010s. I found two reliable pre-2010 sources for information on McCarthy proofs:

- The Author Price Guide (APG) for Cormac McCarthy published by the booksellers Quill and Brush in 2004. For more than a decade the authors, Allen and Patricia Ahearn, compiled every catalog reference to McCarthy. Any book not seen by them should be considered suspect.

- The J. Howard Woolmer Cormac McCarthy collection at the Wittliff Collection at Texas State University (TXST) in San Marcos. Woolmer began collecting McCarthy in 1969. He was a bookseller and a respected bibliographer. He sold his McCarthy collection to TXST in 2006. If he didn’t have an early published McCarthy item in his collection, it should be considered suspect.

“Suspect” does not necessarily mean forged. If a particular proof does not conform to the known real proofs or forgeries described below, a careful examination should be made to determine its authenticity.

In addition to the pre-forgery sources I located, I also consulted Ken Lopez, a specialist in modern first editions who focused on McCarthy early on and who also deals in uncorrected proofs.2 This bibliography would not have been possible without his considerable assistance. Ken and his photographer, Brendan Devlin, examined a large number of forgeries about 2013, took photos, and generously shared them with me. The collector Umberto La Rocca, who has done archival research on McCarthy’s proofs, willingly answered questions for me. A number of other dealers and collectors offered opinions and advice. The conclusions, however, are my own.

Observations on Known Forgeries

For Cormac McCarthy’s first five books, there are more distinct forged proofs than there are real proofs for those novels. (There are also forgeries of proofs of All the Pretty Horses and other books. I will add them in the future, as time permits).

This list was compiled without my ever seeing a forgery in person. I was unable to convince anyone to loan me one to examine, nor were any of the current owners willing to describe in detail the make-up of their forgeries. The conclusions rely on visual evidence from photographs supplemented with the memories of people who have seen them in the past and the surviving archival evidence. But that is more than enough. Once you know what to look for, the forgeries are obvious, it’s figuring out what to look for that is hard.

My analysis of the methods of manufacture devised by the forger are based on the information preserved by Ken Lopez and Brendan Devlin. However, there are variants in the forged proofs that indicate that fakes were produced at different times and the methods used might have changed.

So far, the fabricated UK proof of Suttree is the only forgery that appears to have been done in any sort of edition. I have located three or perhaps four identical or nearly identical copies; presumably there are more. The other fake proofs seem to have been made in smaller batches or perhaps one at a time. Where I have found more than one forgery for a particular proof, it is clear they were made at different times with different cover designs.

The big problem facing the forger of an entire book is how to produce the hundreds of pages required. In most (if not all) cases, the forgeries incorporate printed pages extracted from real books.

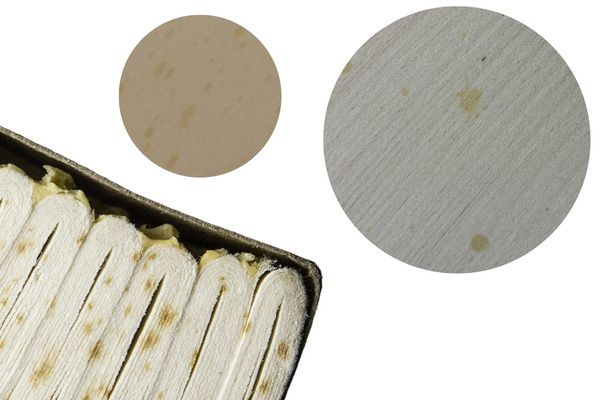

In some cases, the forger used first editions of the Cormac McCarthy’s novels to make fraudulent proofs. This was a reasonable choice because at least two real McCarthy proofs are made from the sheets of first edition books. The invented Chatto & Windus proof of Suttree seems to have used a paperback edition. When dismantled hardcover first editions were used to create forgeries, the forger appears to have variously used ex-library, remaindered, and later printing books for the text block of the fakes. These would have been cheaper to procure. Some forgeries also show evidence that the page block edges were sanded, perhaps to remove library or remainder marks. The UK proofs may have been made from American books, which also would have required the replacement of the title page.

Whatever the source, the sheets (pages) were then glued into paper covers printed with an invented or copied design. In a few cases (the least convincing forgeries), rubber stamps were created to add authenticity to the finished product. There is also evidence that false foxing (spotting) was added to the edges of proofs to make them look older than they are.

For the forgeries of books originally printed in the 1960s to the 1980s, the use of computer fonts is obvious to a practiced eye. But not everyone has a practiced eye so based on Ken Lopez’s photographs taken in the early 2010s, I have identified three hallmarks of the forgeries that can be observed without special training or experience. It is possible, however, that the forgeries improved over time and that these techniques are not sufficient to identify all forged McCarthy proofs. Any collector of McCarthy proofs should be exceptionally careful.

Hallmark 1: The Replacement of the Title/Copyright Leaf

For reasons that are still not completely clear, the forger regularly replaced the title/copyright leaf in the fake proofs with a modern printed sheet.

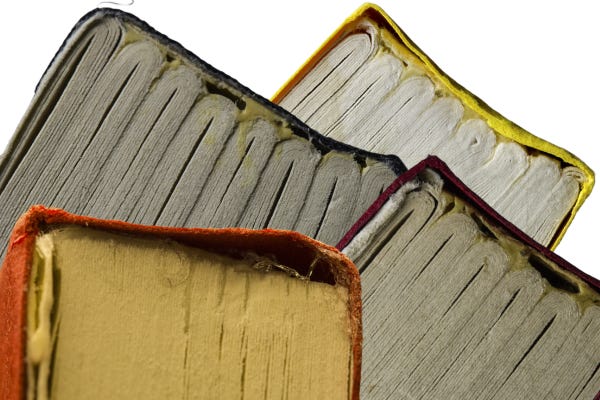

Hallmark 2: Amateurish Binding

The forger was not an experienced bookbinder and does not appear to have had access to professional equipment. As a consequence, there is a homemade look to the bindings (at least the ones seen by Ken Lopez early on—the forger may have improved over time).3 Real proofs are professionally made in almost every case. They are, after all, produced by companies who make books for a living. The design may be simple and the text pages may show corrections, but the books themselves are manufactured, not assembled by clerks with glue sticks.

The fake proofs for which images are available also show a mixture of glues, the original glue used to bind the real book and new glue used to attach the sheets to the paper proof covers.

The inserted title/copyright leafs often protrude from the rest of the page block. Inserting new leaves into an already-bound book is a binding skill that requires practice to do invisibly. The forger did not have enough practice.

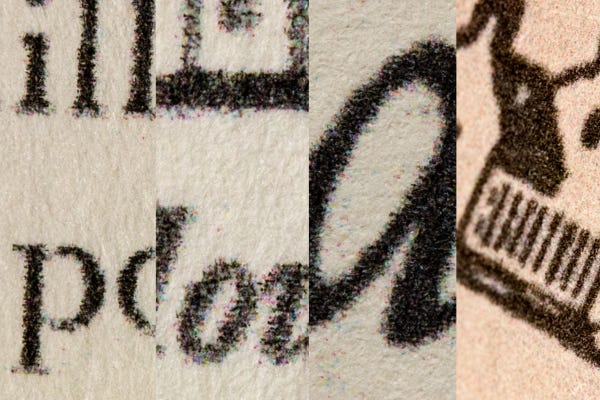

Hallmark 3: The Use of Color Inkjet Technology for Black-and-White Printing

Many color inkjets print blacks using all four ink colors by default (the printer manufacturers say these blacks are richer; I suspect they want users to consume more ink cartridges). The forger was apparently unaware of this and consistently printed in full color. Under magnification, tell-tale spots of cyan (blue), magenta, and yellow inks can be clearly seen on the pages printed by the forger. Similar anachronistic printing can be seen on some of the covers, but this is harder to spot when the fake covers are printed on colored paper.

A Pictorial Guide to Real and Fake Proofs of Cormac McCarthy’s First Five Novels

THE ORCHARD KEEPER

Random House (1965)

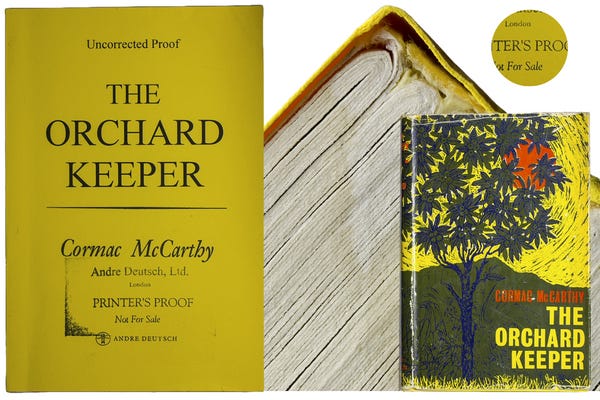

Real US Proof

Covers: Light colored printed wrappers (paper covers), variously described as gray or buff. The paper has a faint vertical pattern.

Page Block: Folded and gathered signatures glued into paper covers. You should be able to clearly see the “loops” of the gatherings (also called signatures).

Notes: Since this proof is made with real folded and gathered sheets, it is better described as an advance reading copy (ARC).4 In this it resembles many of the phony proofs. The real version of the proof does not have a tipped in title page. The text paper color and texture should be the same throughout the book.

This proof is listed in the Ahearns’ APG (McCarthy no. 001a) and a copy is found in the Woolmer collection. No fake copies of this proof have been located but they could exist.

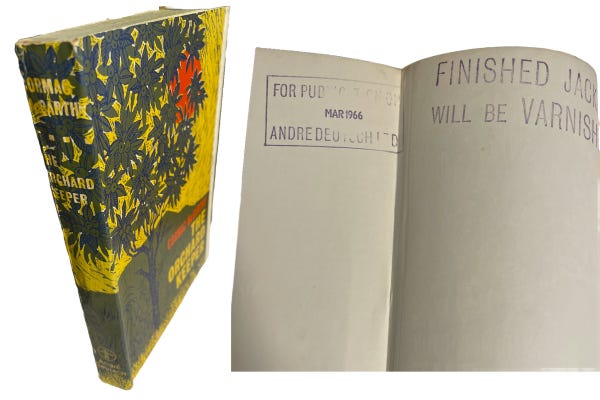

Real UK Proof

Andre Deutsch (1966)

Covers: Proof version of the UK dust jacket with “For Publication/Mar 1966/Andre Deutsch Ltd. Finished Jacket Will Be Varnished” in bold purple lettering on the inside of the front cover (the back or verso of the jacket)..

Page Block: Folded and gathered sheets from the first American edition glued into wrappers made from the trial dust jacket. Green top edge. With a Random House title page.

Notes: This description is from the Ahearns’ APG (#001c), citing a for-sale offering from Waiting for Godot Books in April 2004.

Forgery of the UK Proof

Covers: Bright yellow printed wrappers in a dust jacket.

Page Block: Signatures, with a tipped in title/copyright leaf printed with a color inkjet printer.

Notes: This proof cannot be a second variant of an Andre Deutsch proof because it includes a false title page printed using twenty-first century technology.

The ink stamp on the cover also has an anachronistic element: the straight single quote in the word “printer’s”. Straight quotes were based on typewriter fonts that were ported to early word processors; they were not in general use before the desktop computer era.

The jacket on this proof could be real, but it is more likely a modern recreation.

********************************************

OUTER DARK

No proofs of Outer Dark were made by either Random House in the US or Andre Deutsch in the UK. All Outer Dark proofs should be presumed to be fakes until proven otherwise.

Random House: A search of internet book marketplaces suggests that Random House produced very few paperback proofs in the late 1960s so the lack of a proof of this novel is not especially surprising.

In the late 1960s, Random House instead tended to produce unbound galleys of forthcoming books. Such an advance issue is known for Outer Dark. Galleys are long narrow sheets output from the typesetting equipment of the era. The Ahearns recorded an unbound set of galleys in their APG (#002a), and copies are found in Cormac McCarthy’s archive at TXST.

The collector Howard Woolmer unsuccessfully sought a proof of Outer Dark for many years, and in his papers at TXST is a copy of a letter he wrote to Ken Lopez in 1988 seeking information about this proof.

Forgeries of the US Proof

Two different fake proofs for Outer Dark are known.

US FAKE STYLE 1

Covers: Cream-colored printed wrappers with the title on one line. Information sheet taped to cover (replicating real examples of later McCarthy proofs). Tapebound spine

Page Block: Folded and gathered signatures glued into paper covers. Title/copyright leaf printed on an inkjet and tipped in.5

US FAKE STYLE 2

Covers: Title on two lines. The cover design uses a typeface that is not characteristic of printing in the 1960s. The lower half of the cover copies the design of the real proof of The Orchard Keeper.

Page Block: Unknown

Forgery of the UK Proof

Covers: Tan printed wrappers with the phrase “uncorrected first proof” at the top of the front cover. The tan wrappers on copy of this fake examined by Ken Lopez were printed on white paper (why the forger didn’t just use tan paper cannot be readily explained).

Page Block: Bound from folded and gathered signatures; tipped in title/copyright leaf printing on a color inkjet printer.

Notes: The description of this undoubted forgery is based on an examination of an fake proof seen by Ken Lopez.

Another copy of this proof was sold at auction on December 10, 2019 by Fonsie Mealy as part of lot 716, a group of books from the Philip Murray collection of Cormac McCarthy. The purchaser was a UK bookseller, who consigned it to Forum Auctions in Lonon, which sold the book with a fake UK Child of God proof (see below) on November 30, 2023 for £1,512 (about $1,900).6

I considered the possibility that the Murray Outer Dark proof might have been real and the source of the fake seen by Ken Lopez. Looked at on their own, the fake UK Outer Dark proofs look plausible, until you compare them with other proofs from the same publisher from about the same time.

A strong argument can be made that the Murray copy was also fake, from the cover design alone without knowing how it was constructed.

The key give-away is the phrase “uncorrected first proof” on the cover. This is not typical wording for any proof, let alone an Andre Deutsch proof from the early 1970s.

This phrase comes from Random House, McCarthy’s American publisher, which used that descriptor on proofs for a brief period in the early 1970s, including the real proof of Child of God (1973). Thus, the forger faked a 1970 British proof using a distinctive design element from an American proof published three years later.

There are other elements that don’t pass the sniff test. The addition of the superfluous “by” in front of the author’s name; the italicization of Cormac McCarthy, copied from the Random House proof of The Orchard Keeper; and the use of a contrasting font for the publisher’s name (Andre Deutsch did not have a standard typeface for its proof covers, but it typically used just one type family for the entire text).

The Philip Murray / Fonsie Mealy / Forum proof is thus almost certainly fake. Forum Auctions told me they were going to issue a refund to the purchaser, an American.

********************************************

CHILD OF GOD

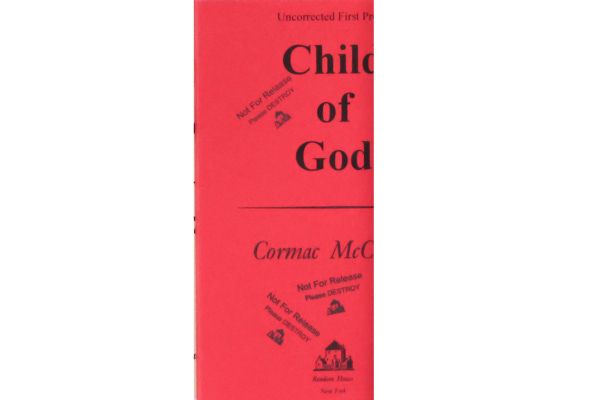

Real US Proof

Random House (1973)

STATE 1: Without Information Sheet

Cover: Red printed wrappers with a double rule in the center. The double rule is slightly wavy. The Random House logo is hand drawn.

Page Block: Unknown (I haven’t been able to confirm if it is perfectbound or bound from folded and gathered signatures).

Notes: This proof of Child of God is recorded in the Ahearns’s APG (#003a). The catalog entry for the copy in the Woolmer collection does not mention the information sheet..

STATE 2: With Information Sheet Taped to Front Cover.

State 2 is the same as State 1, but it has a photocopied information sheet taped to the cover. Heritage Auctions sold a Random House proof of Child of God on October 16, 2009. It did not have and information sheet but it had surface scars where the tape used to be.

Notes: A distinctive feature of this proof is the wording “uncorrected first proof” on the cover, a particular phrasing that appeared on Random House proofs in the early 1970s and rarely on proofs at any other time or by any other publisher.

Forgeries of the US Proof

Two different forgeries of this proof are known.

US FAKE STYLE 1

Covers: Red printed wrappers designed to look very similar to the real US proof. The easiest way to distinguish the two are to look closely at the double rule (line) between the title and the author. The forged rules are computer generated and perfectly straight. The real proof has slightly wavy lines.

Page Block: Folded and gathered signatures with an inkjet-printed title/copyright leaf. The sheets appear to have come from a hardcover copy of the book.

US FAKE STYLE 2

Covers: Red printed wrappers with a design similar to the real Random House proof of The Orchard Keeper and the fake Random House proof of Outer Dark. The distinguishing features between this fake style and the real proof are 1) the real proof was a slightly wavy double rule between the author and the title where this fabrication has a tapered rule; and 2) the real proof uses a hand-drawn logo while the forgery uses a more standard publisher’s logo, probably copied from the Random House Orchard Keeper proof.7

Page Block: Unknown

Notes: As with several other fake proofs, this style can be condemned from its cover design, which is copied from the American proof of The Orchard Keeper. Most likely, this forgery was made before the forger had access to the real proof.

The partial photograph I have found of this style shows a copy that has the order “destroy” rubberstamped many times on the cover.8 The fact that this proof pretends to have been destined for the trash bin made it easier to overlook its design flaws.

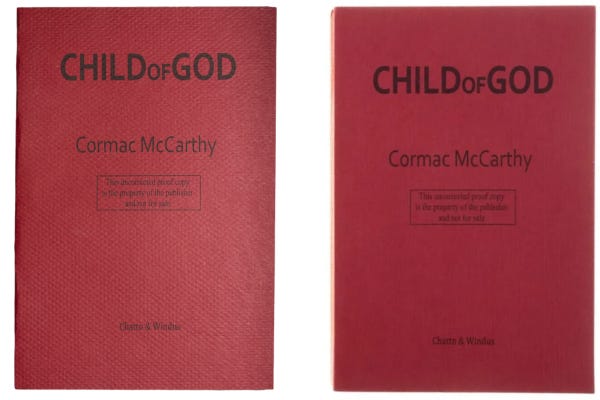

Forgeries of the UK Proof

No legitimate UK proofs of Child of God are known to exist. No copies were recorded in the Ahearns’s APG or in the Woolmer collection. The collector Umberto La Rocca spent time researching this proof in the Chatto & Windus archive at the University of Reading. He told me that there is no record of a proof being printed for this book.

UK FAKE STYLE 1

Covers: Heavily textured paper. The publisher’s logo is closer to the bottom of the front cover.

Page Block: Folded and gathered signatures with a tipped in title/copyright leaf printed with a color laserjet printer.

UK FAKE STYLE 2

The Style 2 UK proof proves that fake proofs were made over time (and not in a single act of forgery).

Cover: Lightly textured paper, with the publisher’s name closer to the bottom of the front cover.

Page Block: Unknown.

Notes: An example of fake Style 2 of the UK proof of Child of God came out of the Philip Murray collection auctioned by Fonsie Mealy in 2019. It later sold at Forum Auctions (2023), a sale cancelled by the auctioneer when the forgery came to light.

While this style of proof has not been examined closely, it can be condemned by its cover design.

Stylistically, this proof is atypical of other proofs from Chatto & Windus from the mid-1970s as the title text is based on the dust jacket design, a feature not seen on any other proofs from the era. In addition, it has a text box noting this copy is “the property of the publisher and not for sale.” This wording and the formatting appears to be based on the real Picador proof for Blood Meridian, which wouldn’t be published for another decade.

A distinguishing feature of the McCarthy forger’s design work are elements that are copied from proof to proof, publisher to publisher, and country to country in a way not seen in real proofs by other authors or among the real proofs for Cormac McCarthy. Proofs typically conform the publisher’s current house style and not to previous or future proofs for other books and different editions.

********************************************

SUTTREE9

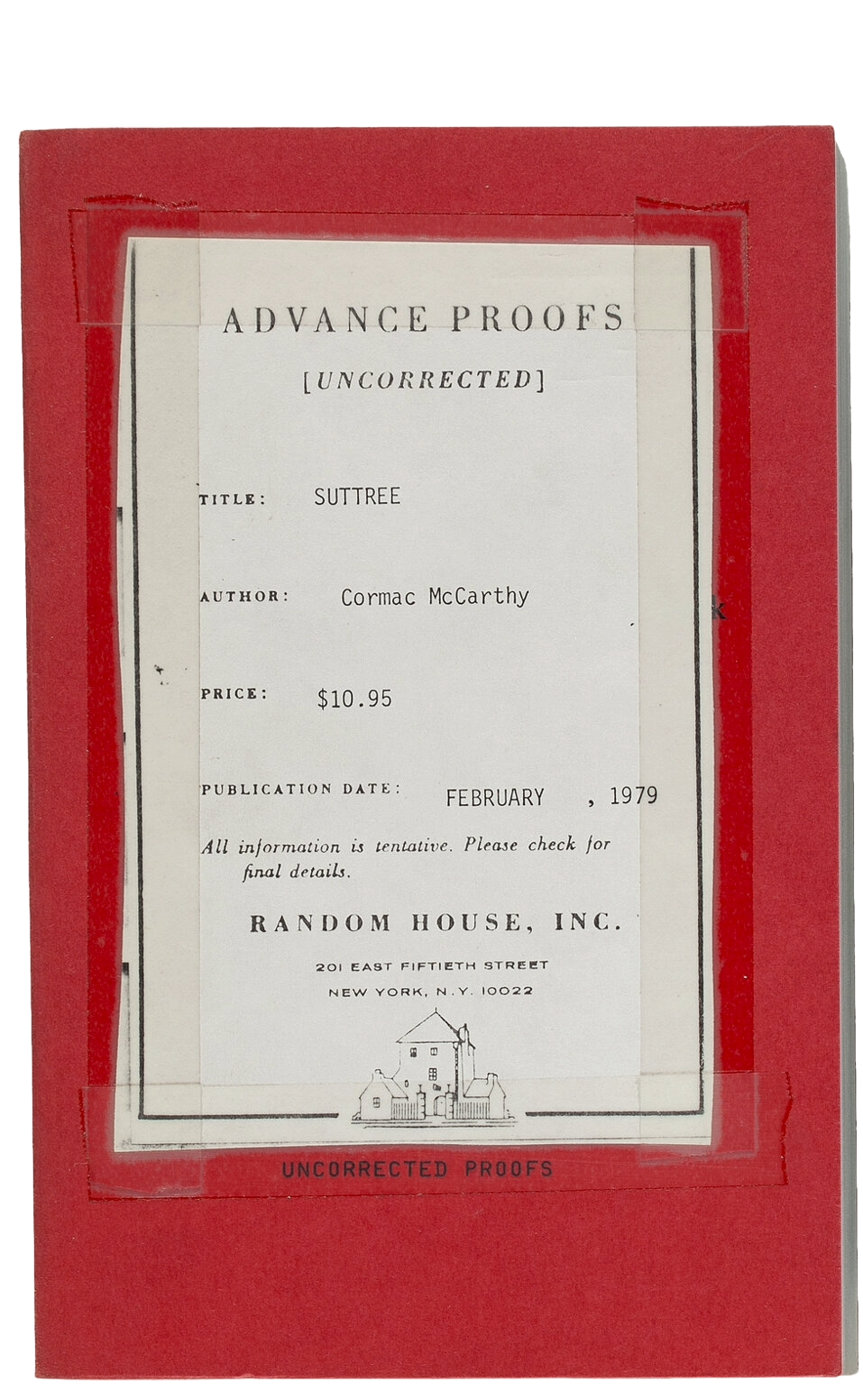

Real US Proof

Random House (1979)

US PROOF STATE 1

Covers: Red printed wrappers without an information sheet taped to the front cover.

Page Block: Unknown

Notes: I have not found an image of the proof without the information sheet. A copy of this proof is listed in the Ahearns’ APG (#004a). A copy is also recorded in the Woolmer collection which is apparently State 1, with a “book synopsis” laid in. No forgery of this proof has been reported.

US PROOF STATE 2

Same as State 1 but with an information sheet taped to the front cover.

Notes: No forgery of this proof has been reported.

Forgery of the UK Proof

No proof of this book was issued and any book purporting to be a proof should be considered extremely suspect.

Covers: Red textured printed wrappers, with the title reproducing the title-page design.

Page Block: Perfectbound. Umberto La Rocca has identified the page block of at least one copy are coming from the 1992 Vintage Books paperback which omitted the acknowledgements page which is opposite the copyright page in all other editions. The title page is recreated using a slightly wrong font (see below). The page block may be from a paperback copy or perhaps photocopied from a paperback copy.

Notes: The UK first edition of Suttree was made in the US from finished American books. The title/copyright leaf was removed and new one with the British publisher’s name was tipped in (in technical book terms, the title leaf is a cancel). The spine of the UK first edition says Random House, not Chatto & Windus. Chatto & Windus designed and printed a different dust jacket for the novel.

It does not seem logical for Chatto & Windus to produce a proof of the novel when they didn’t even bother to put their name on the outside of the finished book. The collector Umberto La Rocca says that there is no record of Chatto & Windus producing a proof for their edition of Suttree in the publisher’s archive at the University of Reading.

The cover design of the fake proof is not characteristic of Chatto & Windus proofs of the era, which use straightforward typesetting, just like the American proofs. Further condemning this proof is the fact that the copyright page is a re-creation of the real UK title page, but the font is wrong.

A Note on Foxing

A known fake of the UK edition of Outer Dark has heavy foxing on the page edges. The forged UK Suttree proof photographed by Ken Lopez in the early 2010s and the Paul Ford/BooksCurious/Burnside Rare Books copy that I wrote about in my newsletter also had foxing on the top edge (they may be the same copy, but the photographs are not clear enough to say for sure).

The Suttree foxing may be faked; it has the appearance of a coffee splatter. The forger may have used this and other fake aging techniques to disguise the recent printing of the proof covers.

********************************************

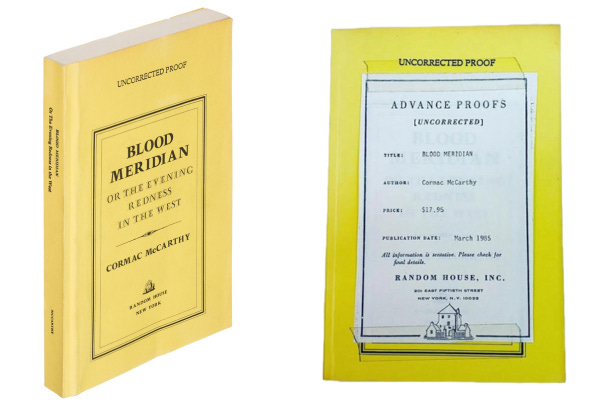

BLOOD MERIDIAN

Real US Proof

Random House (1985)

US PROOF STATE 1

Covers: Printed yellow wrappers without an information sheet on the cover.

Page Block: Perfectbound

A copy of this proof is found in the Woolmer collection with an information sheet laid in. It is also listed in the Ahearns’ APG (#005a). No forgery of this proof has been reported.

US PROOF STATE 2

Same as State 1 but with an information sheet taped to the front cover.

Notes: No forgery of this proof has been reported.

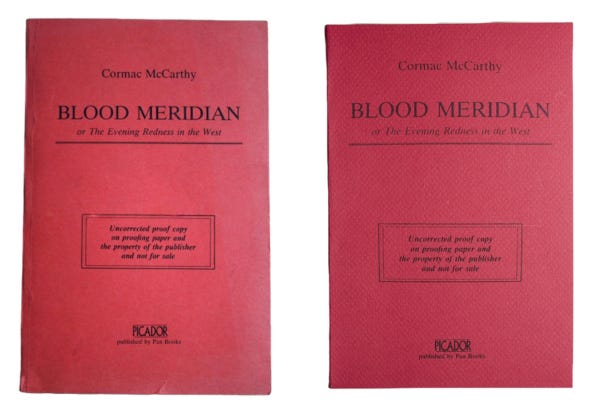

Real UK Proof

Picador (1989)

Covers: Red printed wrappers.

Page Block: Uncertain. The cover says the page block is printed on “proofing paper.” How this is different from regular paper is unclear.

Notes: A copy of this proof is listed in the Ahearns’ APG (#005c) and a copy can be found in the Woolmer collection at TXST.

Fake UK Proof

The cover of the forged proof of the Picador edition of Blood Meridian is the best of the fakes. The most obvious difference is that the publisher’s logo is closer to the bottom edge on the fake than on the real proof.

Covers: Printed red textured wrappers.

Page Block: Bound from folded and gathered signatures from a hardcover book.

********************************************

Forgeries of Other McCarthy Proofs

Faked copies of the UK proofs of All the Pretty Horses and The Stonemason exist. There are also fakes of a fictitious illustrated edition of Blood Meridian and of a supposedly scrapped signed, limited edition of The Road.

Be careful out there.

—Scott Brown, Updated April 10, 2024

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

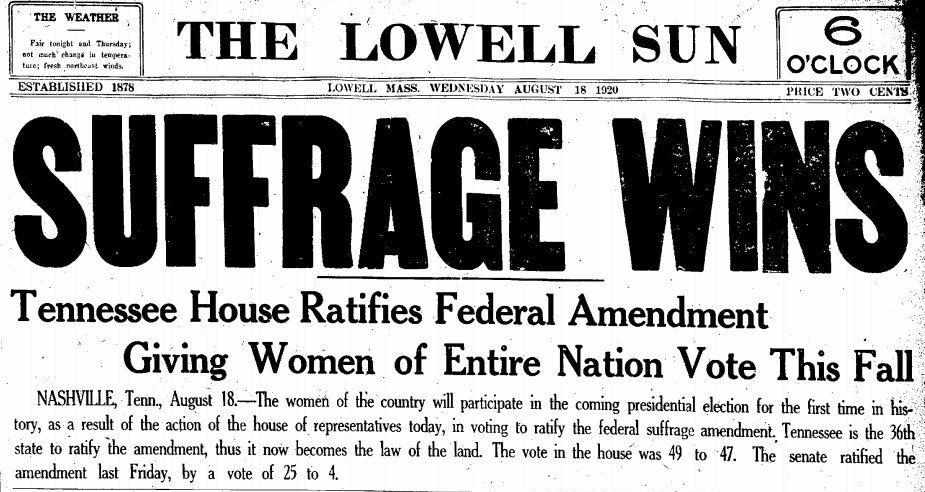

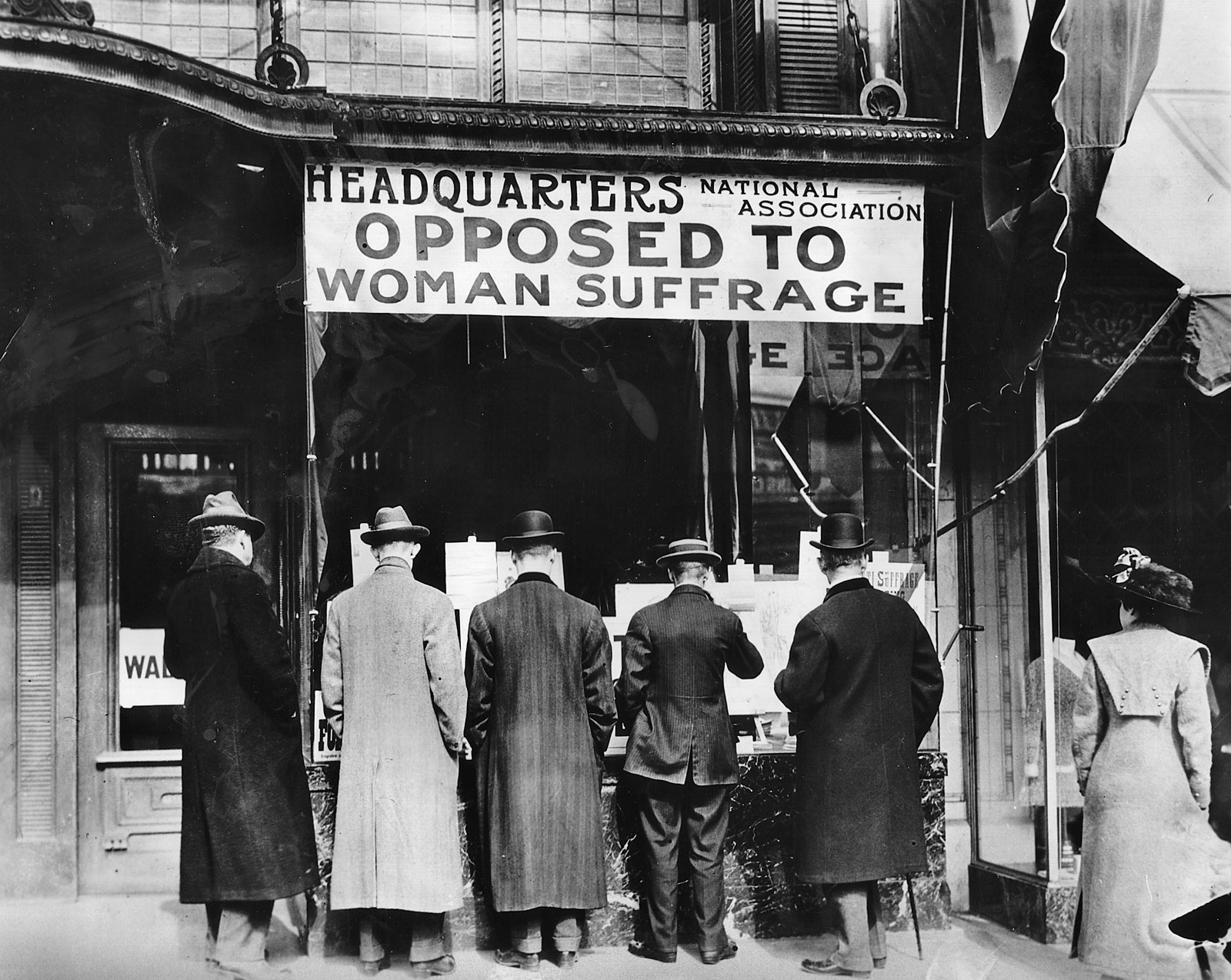

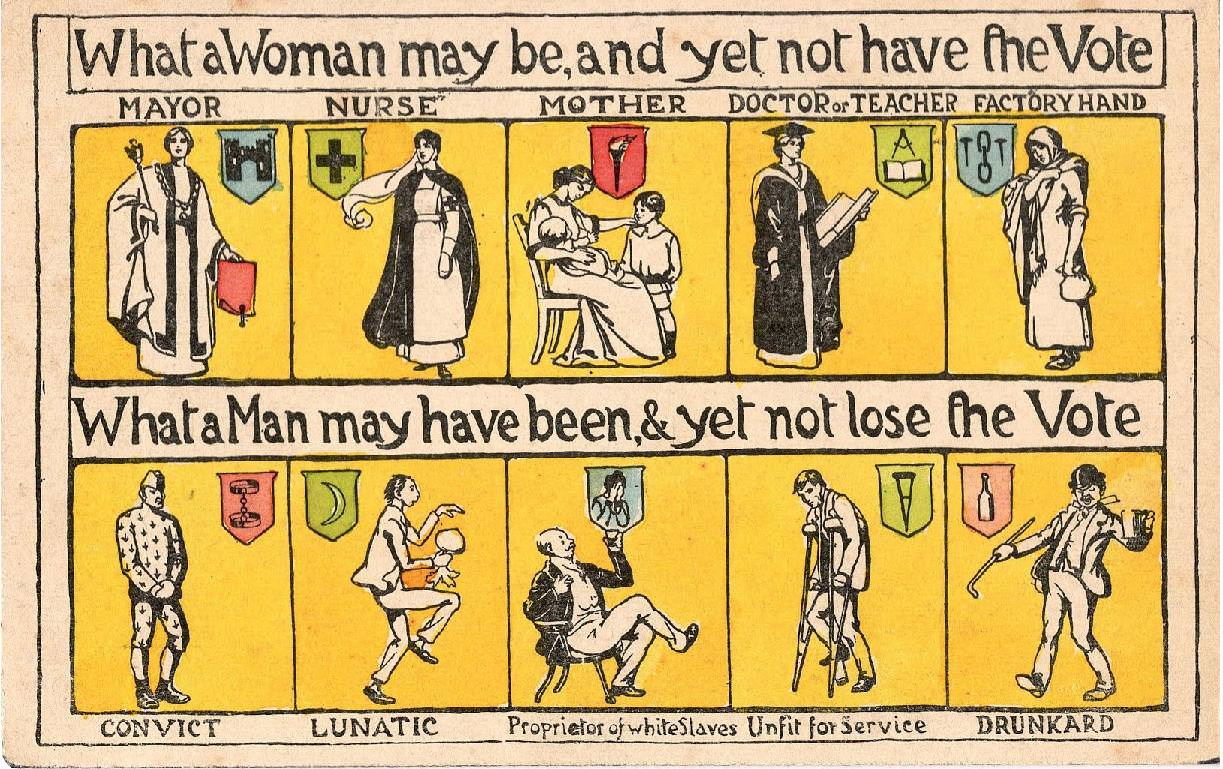

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.

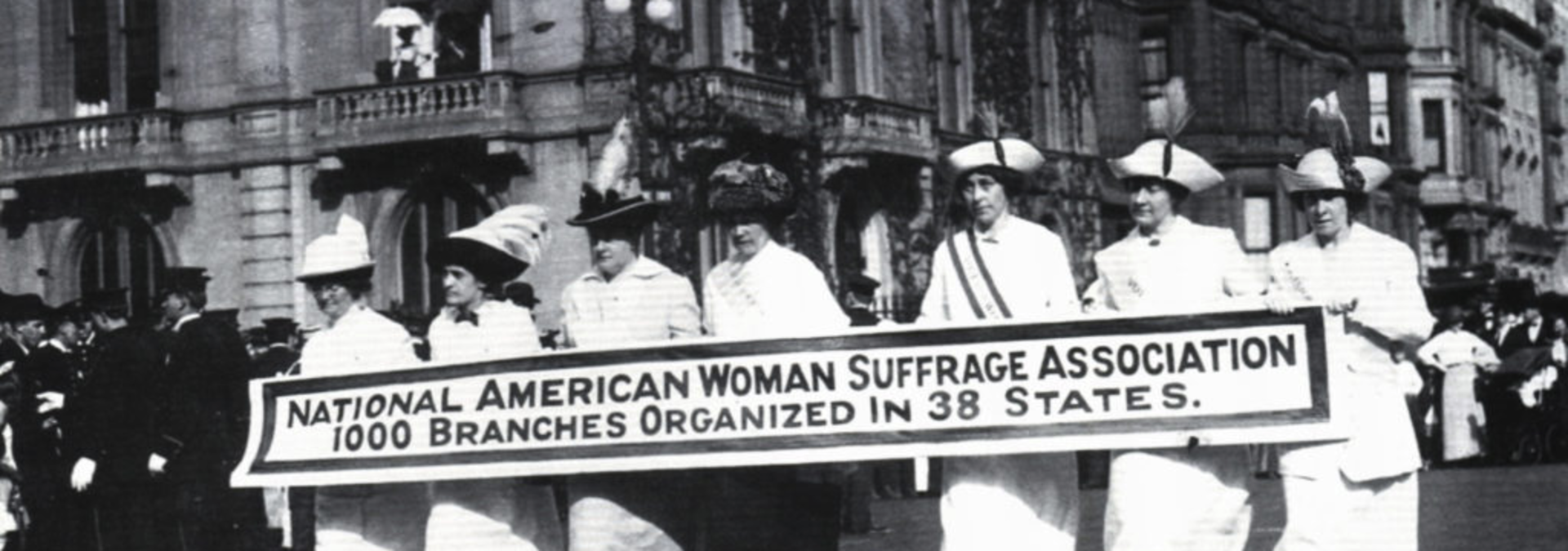

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.  In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

Carson eventually got a temporary position with the United States Bureau of Fisheries, a job which she had been on the fence about but was persuaded to take by one of her college mentors. She spent her time there writing radio copy for “weekly educational broadcasts entitled Romance Under the Waters.” With 52 programs in the series, Carson had her work cut out for her. The episodes focused on aquatic life and was meant to prompt interest in biology of fish and the work the Bureau did. During this time, Carson’s interest in marine life grew, and soon she was submitting articles on aquatic life in the Chesapeake Bay to local newspapers and magazines. She impressed her superiors with her dedication and knowledge to the point where they offered her the first full-time position that became available, as a junior aquatic biologist.

Carson eventually got a temporary position with the United States Bureau of Fisheries, a job which she had been on the fence about but was persuaded to take by one of her college mentors. She spent her time there writing radio copy for “weekly educational broadcasts entitled Romance Under the Waters.” With 52 programs in the series, Carson had her work cut out for her. The episodes focused on aquatic life and was meant to prompt interest in biology of fish and the work the Bureau did. During this time, Carson’s interest in marine life grew, and soon she was submitting articles on aquatic life in the Chesapeake Bay to local newspapers and magazines. She impressed her superiors with her dedication and knowledge to the point where they offered her the first full-time position that became available, as a junior aquatic biologist. Over ten years at the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (as it was by then called) were good to Carson – she had become the chief editor of publications. Years after the first interest shown by publishers, Carson was once again on the book-publishing path. This time, Oxford University Press expressed interest in a life history of the ocean. Her completed work would eventually become The Sea Around Us. Several chapters were published serially in the Yale Review, Science Digest and The New Yorker, until it was finally published as a book in July 1951. It was an immediate bestseller, remaining at the top of the New York Times Bestseller List for 86 weeks straight. This success gave Carson the ability to give up her job at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and focus on her writing full time.

Over ten years at the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (as it was by then called) were good to Carson – she had become the chief editor of publications. Years after the first interest shown by publishers, Carson was once again on the book-publishing path. This time, Oxford University Press expressed interest in a life history of the ocean. Her completed work would eventually become The Sea Around Us. Several chapters were published serially in the Yale Review, Science Digest and The New Yorker, until it was finally published as a book in July 1951. It was an immediate bestseller, remaining at the top of the New York Times Bestseller List for 86 weeks straight. This success gave Carson the ability to give up her job at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and focus on her writing full time. Her books on the ocean life continuing to be popular, best selling works across the country, Carson began focusing much of her research on pesticide use in the United States, something she had been interested in for over a decade, but finally had the time and space to work on it. By 1957, the USDA was proposing widespread pesticide spraying – to eradicate fire ants and other pests. Carson was suspicious of some of the toxic chemicals they were proposing using, including DDT – a now known carcinogen. She worried what kind of effect the runoff from this activity would have on coastal life, and for good reason. Carson would spend the rest of her life focusing her efforts on conservation, with a great emphasis on “the dangers of pesticide overuse.” In September 1962, Houghton Mifflin published what would become Carson’s best-known book, Silent Spring. This work described in detail the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment, and is credited worldwide with helping begin the modern environmental movement. “Carson was not the first, or the only person to raise concerns about DDT, but her combination of “scientific knowledge and poetic writing” reached a broad audience and helped to focus opposition to DDT use.” She also poetically noted the dangers of human nature on the environment, a verifiable fact . Carson was, truly, ahead of her time. Unfortunately taken from us much too soon (passing away at the age of only 56 after a battle with breast cancer), Rachel Carson will live on with every moment that we choose to put the good of the planet above ease of our lives.

Her books on the ocean life continuing to be popular, best selling works across the country, Carson began focusing much of her research on pesticide use in the United States, something she had been interested in for over a decade, but finally had the time and space to work on it. By 1957, the USDA was proposing widespread pesticide spraying – to eradicate fire ants and other pests. Carson was suspicious of some of the toxic chemicals they were proposing using, including DDT – a now known carcinogen. She worried what kind of effect the runoff from this activity would have on coastal life, and for good reason. Carson would spend the rest of her life focusing her efforts on conservation, with a great emphasis on “the dangers of pesticide overuse.” In September 1962, Houghton Mifflin published what would become Carson’s best-known book, Silent Spring. This work described in detail the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment, and is credited worldwide with helping begin the modern environmental movement. “Carson was not the first, or the only person to raise concerns about DDT, but her combination of “scientific knowledge and poetic writing” reached a broad audience and helped to focus opposition to DDT use.” She also poetically noted the dangers of human nature on the environment, a verifiable fact . Carson was, truly, ahead of her time. Unfortunately taken from us much too soon (passing away at the age of only 56 after a battle with breast cancer), Rachel Carson will live on with every moment that we choose to put the good of the planet above ease of our lives.