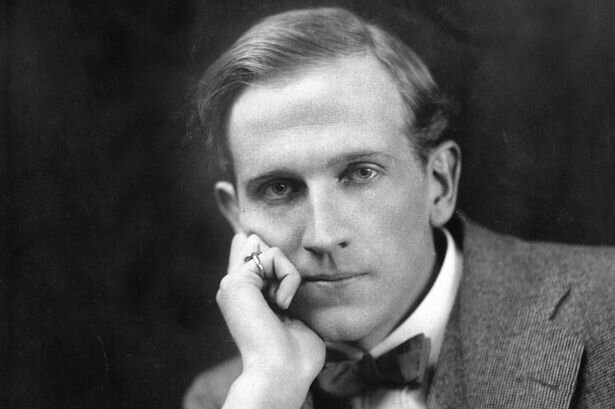

In the enchanted world of children’s literature, a few household names stand out to the average reader. Not many of them evoke the same sense of nostalgia and peace in us as A. A. Milne – the creator of Winnie-the-Pooh. On this the anniversary of his death, we wanted to take a look at what made Pooh, the endearing inhabitants of the Hundred Acre Wood, and A. A. Milne unique, and how he crafted stories that continue to this day to captivate generations both young and old.

Born on January 18, 1882, Alan Alexander Milne lived a relatively peaceful childhood. He was brought up in London, attended the small independent school his father ran (fun fact: at one point H.G. Wells was one of Milne’s teachers!), and then went on to the Westminster School and to Trinity College, Cambridge where he received a B.A. in Mathematics. He was a talented cricket player and played on a couple different teams, one of which was the Allahakbarries, Peter Pan author J. M. Barrie’s cricket team (along with teammates such as Arthur Conan Doyle and P.G. Wodehouse). To say that Milne was privileged and knew all the right people to join the literary scene was an understatement!

After his graduation, Milne wrote humorous essays and articles for Punch magazine. While working for Punch, he published 18 plays and three novels, all of which were well received (even if they did not achieve the literary acclaim that Pooh did, years later). In 1913 he married, and in 1920 his son, Christopher Robin, was born. Milne served in both WWI and later WWII, and considered himself a very proud Englishman.

After a successful career as a playwright and humorist, Milne turned to his son Christopher Robin for inspiration in his next work. Not yet called “Pooh”, Christopher Robin’s bear first appeared in Milne’s poem “Teddy Bear” in Punch magazine in 1924. He then appeared on Christmas Eve in 1925, in the London Evening News in a short story. Winnie-the-Pooh, however, made headlines in the first book about him, published in 1926, when Christopher Robin was six years old. Two years later, Milne published The House at Pooh Corner, the second book set in the Hundred Acre Wood. Throughout this time, Milne continued working on other things, and even published four plays in these “Pooh” years.

Both Milne and Christopher Robin’s relationship with Winnie-the-Pooh was strained. During his childhood years, they enjoyed a close personal relationship. However, soon A. A. Milne found himself disappointed that his childish work was overshadowing the multitude of other works he had created over the years. He hated the constant demand for more Pooh stories, and he wished to be taken more seriously as an author than he felt he was. On Christopher Robin’s part, he was relentlessly bullied at school for being the Christopher Robin, and ended up resenting his father for trapping him forever in association with the popular children’s story. We like to think that this bit of Pooh’s history reminds us that art and life aren’t always two completely separate things.

That being said, how has Pooh pulled on our heartstrings the way he has, for almost a hundred years now? We believe that the simplicity and innocence of the Hundred Acre Wood, which is an idyllic place in and of itself, serves as a safe refuge for us, even in our imaginations. The gentle humor and (often pretty profound) wisdom of the books invites all ages to enjoy them. Pooh himself reminds us of the joy of simple pleasures – from a jar full of honey to a day out with a good friend.

As we celebrate the life and legacy of A. A. Milne and Winnie-the-Pooh, we are reminded in an often chaotic and uncertain world to cherish moments of joy, embrace our sense of childish wonder, and hold fast to our friendships – for these are the things that will sustain us through rough times.

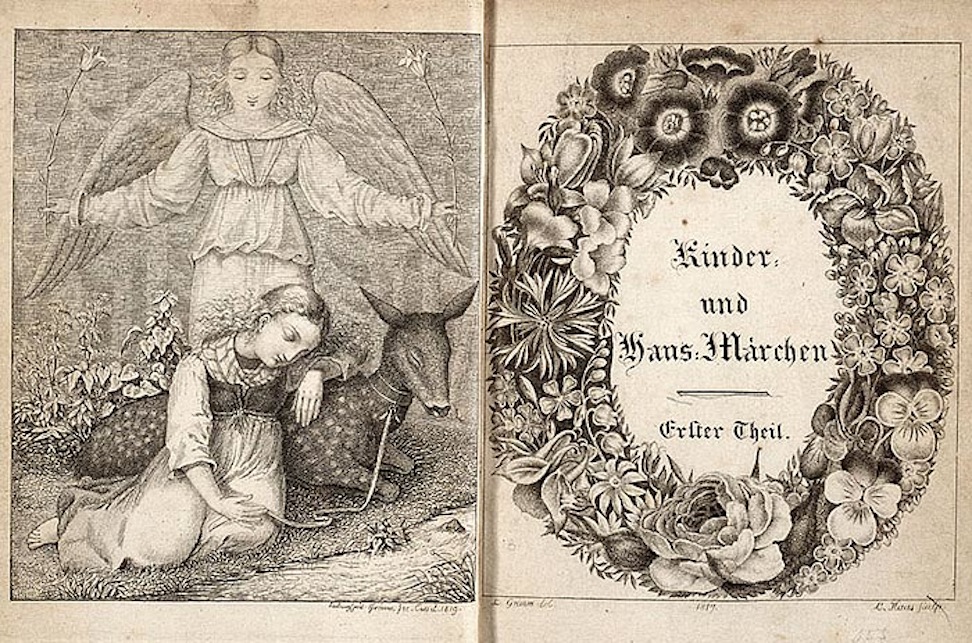

The two attended the University of Marburg together, where they tried to study law. I say “tried”, because here the brothers once again met adversity due to their reduced social status. Treated as outcasts, without the benefit of receiving financial aid or stipends as some of the wealthier students received (explain THAT one, if you can), the brothers once again turned to each other for comfort and worked hard in their studies. It was at the University of Marburg that the pair first became interested in medieval German literature and more simplistic, romantic ways of writing that the modern day seemed to have forgotten. This interest in folklore and poetry and traditional “German” culture influenced the brothers for the rest of their lives. They wished to see the unification of the over 200 principalities into a single, unified state, and spent much of their time with their inspiring law professor Friedrich von Savigny and his friends. It was through these romantics that the Grimm brothers were introduced to the literary beliefs of Johann Gottfried Herder – a German philosopher who felt that literature of the area should revert back to simplicity, and focus more on nature, humanity and beauty. The boys credited their devotion to their studies in Germanic literature and culture as a saving grace in a dark time – outcasts amongst their peers. Wilhelm himself wrote, “the ardor with which we studied Old German helped us overcome the spiritual depression of those days.”

The two attended the University of Marburg together, where they tried to study law. I say “tried”, because here the brothers once again met adversity due to their reduced social status. Treated as outcasts, without the benefit of receiving financial aid or stipends as some of the wealthier students received (explain THAT one, if you can), the brothers once again turned to each other for comfort and worked hard in their studies. It was at the University of Marburg that the pair first became interested in medieval German literature and more simplistic, romantic ways of writing that the modern day seemed to have forgotten. This interest in folklore and poetry and traditional “German” culture influenced the brothers for the rest of their lives. They wished to see the unification of the over 200 principalities into a single, unified state, and spent much of their time with their inspiring law professor Friedrich von Savigny and his friends. It was through these romantics that the Grimm brothers were introduced to the literary beliefs of Johann Gottfried Herder – a German philosopher who felt that literature of the area should revert back to simplicity, and focus more on nature, humanity and beauty. The boys credited their devotion to their studies in Germanic literature and culture as a saving grace in a dark time – outcasts amongst their peers. Wilhelm himself wrote, “the ardor with which we studied Old German helped us overcome the spiritual depression of those days.” The brothers did not immediately turn to transcribing Germanic folklore for the masses. As they were solely responsible, as the oldest boys (primarily Jacob) of the family, for their sibling and mother’s livelihood (because that’s what they needed… more stress), Jacob accepted a job in Paris as assistant to his once-professor (von Savigny). On his return to Marburg he gave this post up to take a job with the Hessian War Commission. Their circumstances remained dire – as it seemed almost impossible for Jacob to support them all on his own. Food was often scarce and the brothers suffered emotionally. In 1808, Jacob found a more appropriate (to his interests) job as the librarian to the King of Westphalia, and soon after went on to become the librarian in Kassel, where the two boys had attended their gymnasium (high school, for all intents and purposes). Jacob supported his siblings once their mother passed away, and he even paid for Wilhelm to receive medical attention that year to seek treatment for respiratory problems. After Wilhelm’s recovery, he joined his brother as a librarian in Kassel.

The brothers did not immediately turn to transcribing Germanic folklore for the masses. As they were solely responsible, as the oldest boys (primarily Jacob) of the family, for their sibling and mother’s livelihood (because that’s what they needed… more stress), Jacob accepted a job in Paris as assistant to his once-professor (von Savigny). On his return to Marburg he gave this post up to take a job with the Hessian War Commission. Their circumstances remained dire – as it seemed almost impossible for Jacob to support them all on his own. Food was often scarce and the brothers suffered emotionally. In 1808, Jacob found a more appropriate (to his interests) job as the librarian to the King of Westphalia, and soon after went on to become the librarian in Kassel, where the two boys had attended their gymnasium (high school, for all intents and purposes). Jacob supported his siblings once their mother passed away, and he even paid for Wilhelm to receive medical attention that year to seek treatment for respiratory problems. After Wilhelm’s recovery, he joined his brother as a librarian in Kassel.

After being slighted for a job promotion, the brothers eventually moved to Göttingen where they became professors of German studies at the University (Jacob also as head librarian), and continued to write and publish works on Germanic folklore, mythology and country tales for a few years. The brothers moved to Berlin in their later years, working at the University of Berlin and also editing their German Dictionary, which would become one of their most prominent works.

After being slighted for a job promotion, the brothers eventually moved to Göttingen where they became professors of German studies at the University (Jacob also as head librarian), and continued to write and publish works on Germanic folklore, mythology and country tales for a few years. The brothers moved to Berlin in their later years, working at the University of Berlin and also editing their German Dictionary, which would become one of their most prominent works.

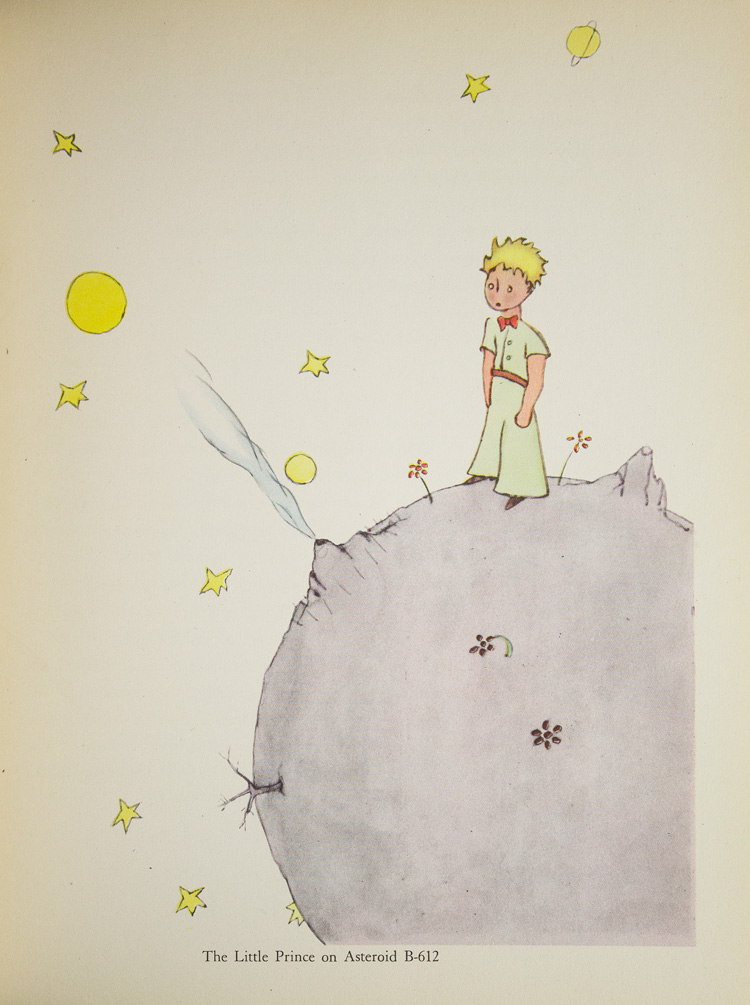

So said the Little Prince – an absolutely beloved character in the canon of Western Literature. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote this story, a children’s story on the outside and a very adult study of human nature and morality on the inside. Saint-Exupéry, a French national, had fled Europe at the onset of World War II and wrote much of his tale during his 27 week stay in North America and Canada. Now normally we would do a blog on Saint-Exupéry’s life story and how he came to write such a popular and precious children’s tale, but today we are speaking of a specific day in this author’s life… the day he disappeared from the skies.

So said the Little Prince – an absolutely beloved character in the canon of Western Literature. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote this story, a children’s story on the outside and a very adult study of human nature and morality on the inside. Saint-Exupéry, a French national, had fled Europe at the onset of World War II and wrote much of his tale during his 27 week stay in North America and Canada. Now normally we would do a blog on Saint-Exupéry’s life story and how he came to write such a popular and precious children’s tale, but today we are speaking of a specific day in this author’s life… the day he disappeared from the skies.

Unfortunately,

Unfortunately,

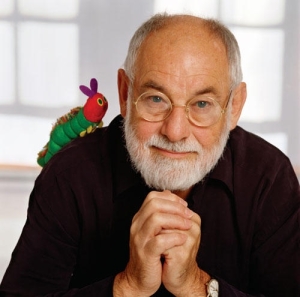

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at  It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.

It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.