In the grand scheme of things, what is 100 years? In terms of your lifespan, it may seem like a lot. In terms of history, on the other hand? Well, in terms of history it is a mere slip in time. Now what would you say if you were to realize that American women have only had certain rights – specifically the right to vote – for this amount of time? 100 years ago today, Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment… stating that American citizens could not be denied the right to vote based on their sex – effectively giving women the chance to make their voices heard. It was not an easy battle! In fact, in the US, support for the suffrage movement began as early as the 1840s! It would take over 80 years for their demands to be instituted. Let’s take a look back at this time in history and see how lives were changed for the better, 100 years ago today.

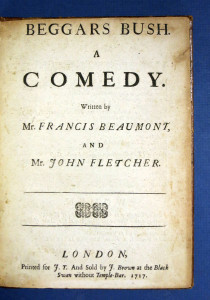

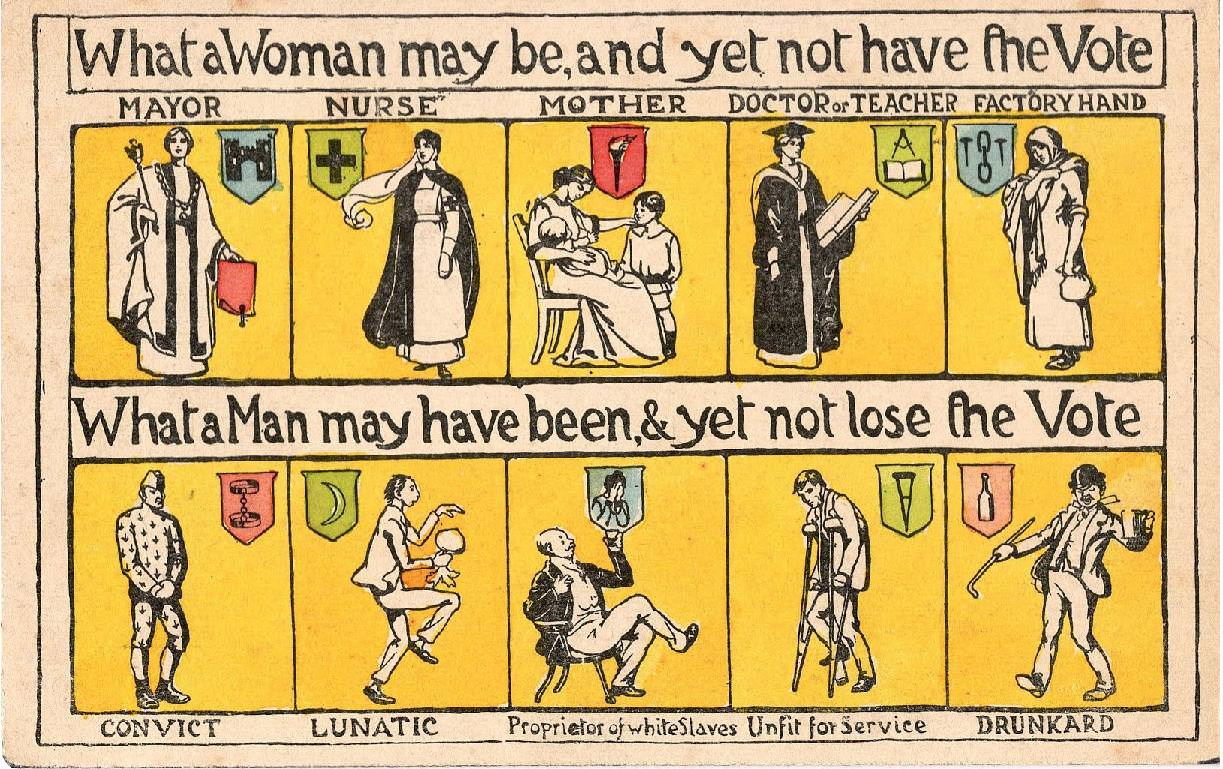

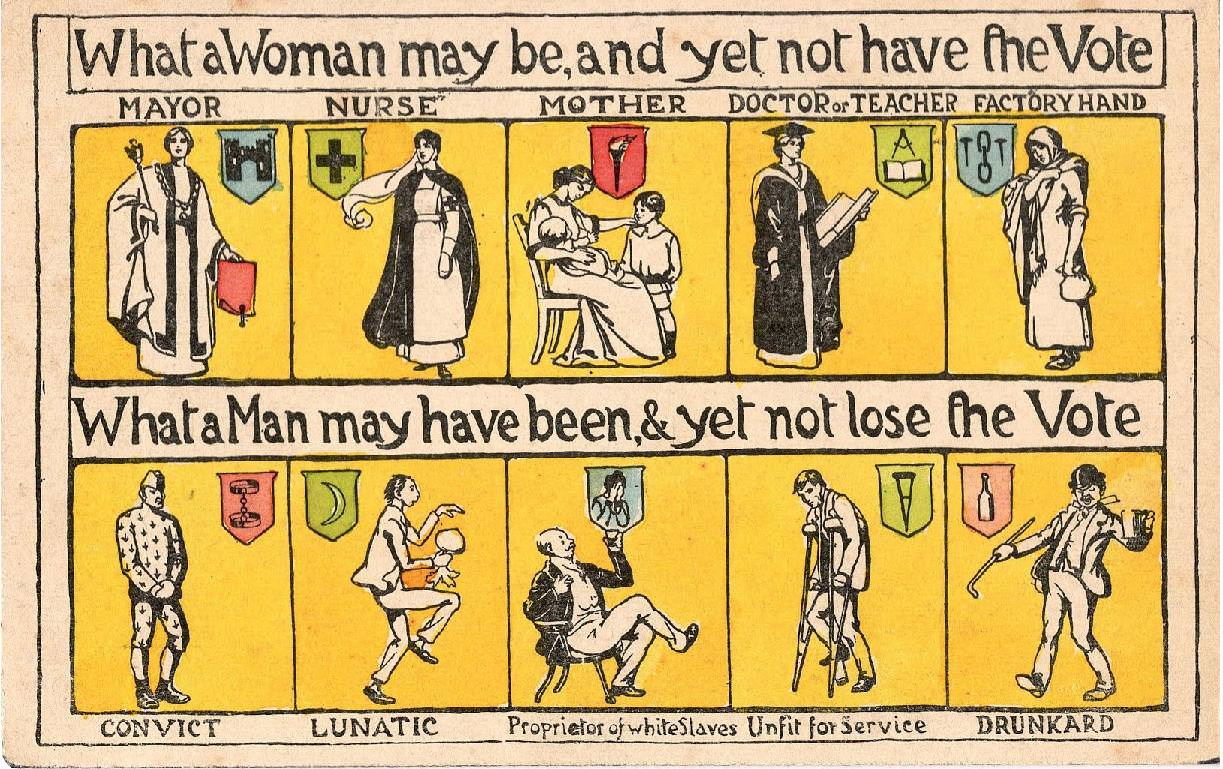

Some tend to trace the modern suffrage movement (knowing and understanding that women should have always had equal rights as men) back to a specific publication that we all know – Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 UK publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Women. Wollstonecraft was known for being revolutionary in her ideas, and a stalwart for women’s intelligence and respect. It is said by some that her work helped inspire Sarah Grimké’s 1838 The Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women – the work which made abolitionist Grimké to be considered the “mother of the women’s suffrage movement”. Her work, widely circulated from Boston throughout the early United States, helped inspire many hundreds (if not thousands) to begin the quest for women’s rights. The main hurdle that women had to jump before these rights could be established, however, was the idea of the pure, innocent woman – one who did not belong in the public sphere. Long considered roles for men only, women becoming part of the public and even political spheres was shocking and highly looked down upon in the early 1800s. In the 1830s and 40s, the abolition of slavery and women’s rights seemed to partner well together, as most women speaking publicly were speaking out condemning slavery… and the act of doing so was automatically a boon for the rights of women. The radical wing (both men and women) of the abolitionist movement were well-known for their support of women’s rights. Unfortunately, towards the beginning, that radical wing consisted of very little of the general population.

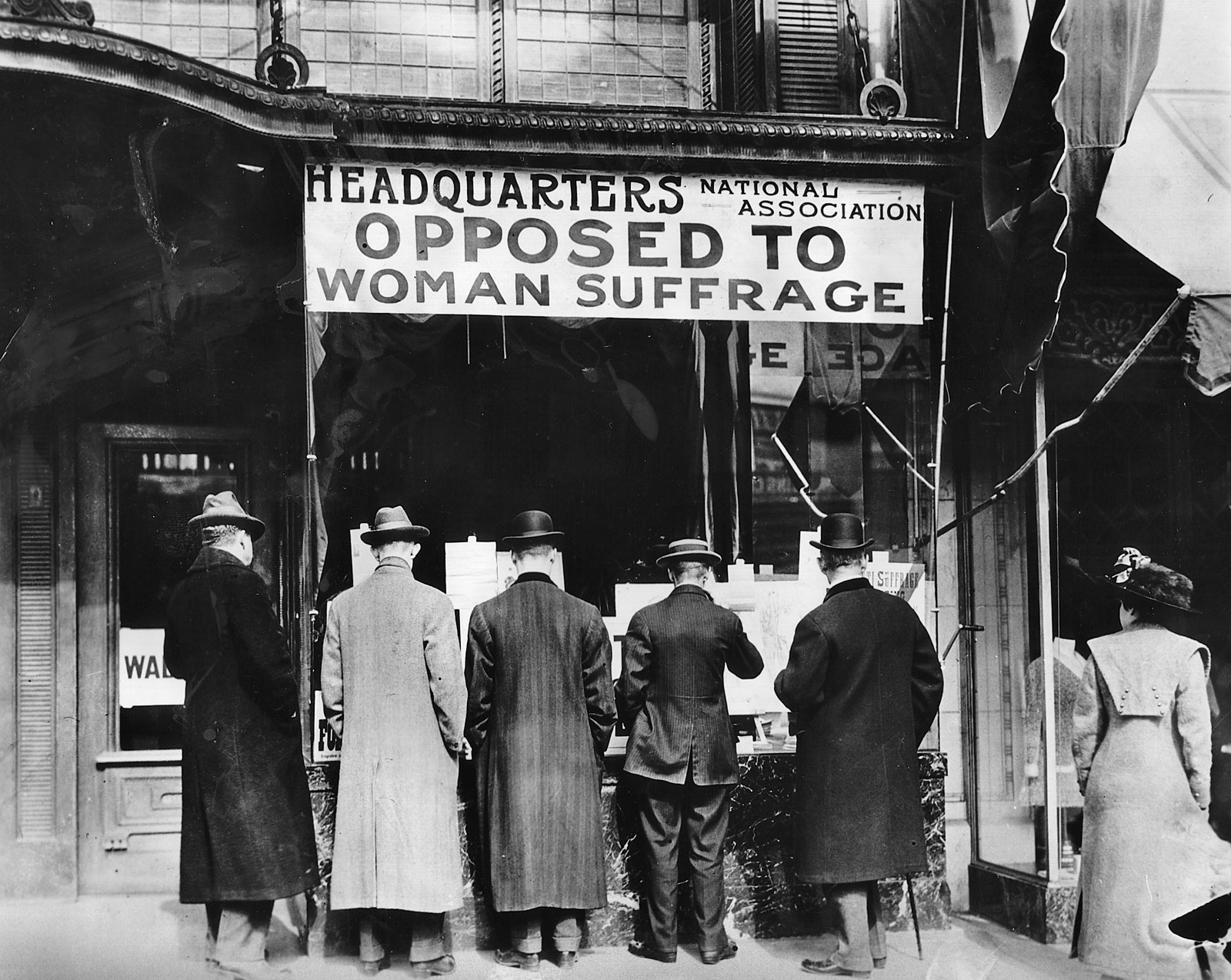

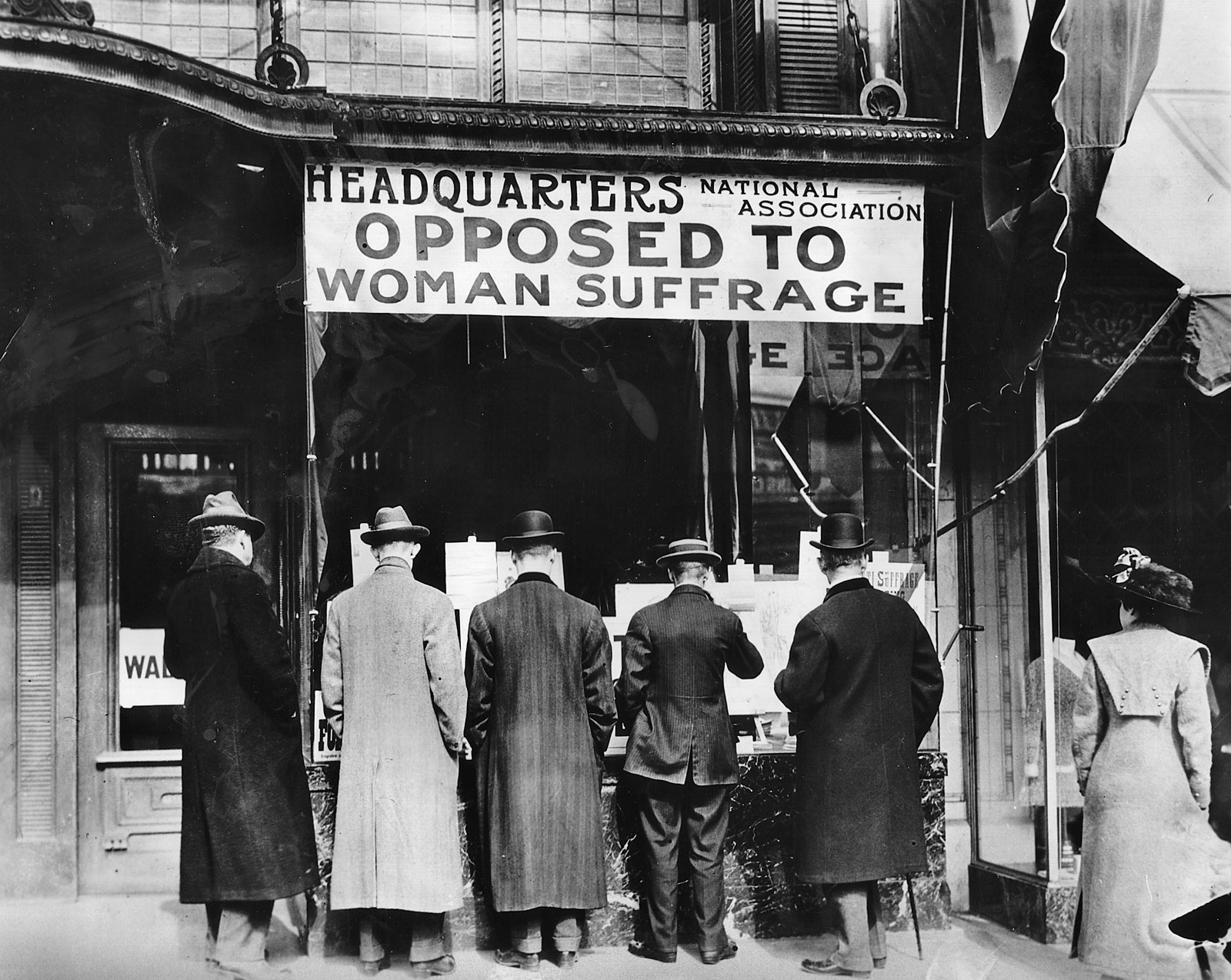

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.

The Seneca Falls Convention in New York in 1848 marked a specific shift in women’s suffrage. Abolitionist activists, both men and women, gathered to discuss women’s civil rights. Almost all of the delegates agreed… women were autonomous beings, independent of their husbands, and ought to share the same rights as their brothers and husbands. Adopting the Declaration of Independence to their beliefs, the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments proclaimed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Amen to that!

Though the women’s movement lost a bit of momentum and support during the Civil War (rightly so), almost as soon as it ended the issues of suffrage and equality reared up again, what with the 14th and 15th Amendment changes for the rights of men of color. Over the next few years, several associations formed to highlight women’s rights, suffrage being only a part of the demands of their followers. Shockingly, equal pay for equal jobs was a large demand of the women in this period. Throughout the Civil War, women picked up the slack needed as men were away fighting. They performed men’s tasks and men’s jobs (all while keeping house and raising children), and some kept this work up even after the war. Their significantly lower pay for the same work highlighted an extreme disparity with how men and women were treated at the time. Associations like the Women’s Loyal National League, the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), and the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) all held strong beliefs and fought for similar rights (though even they were sometimes on opposing sides of the same team).

In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

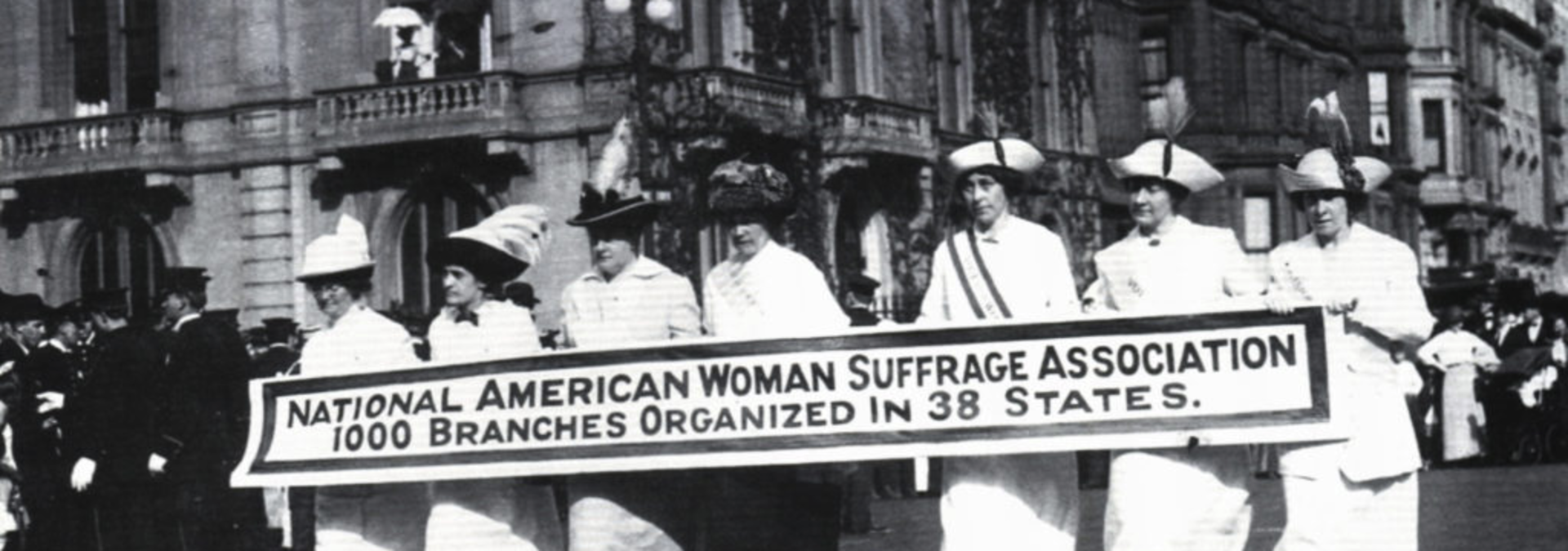

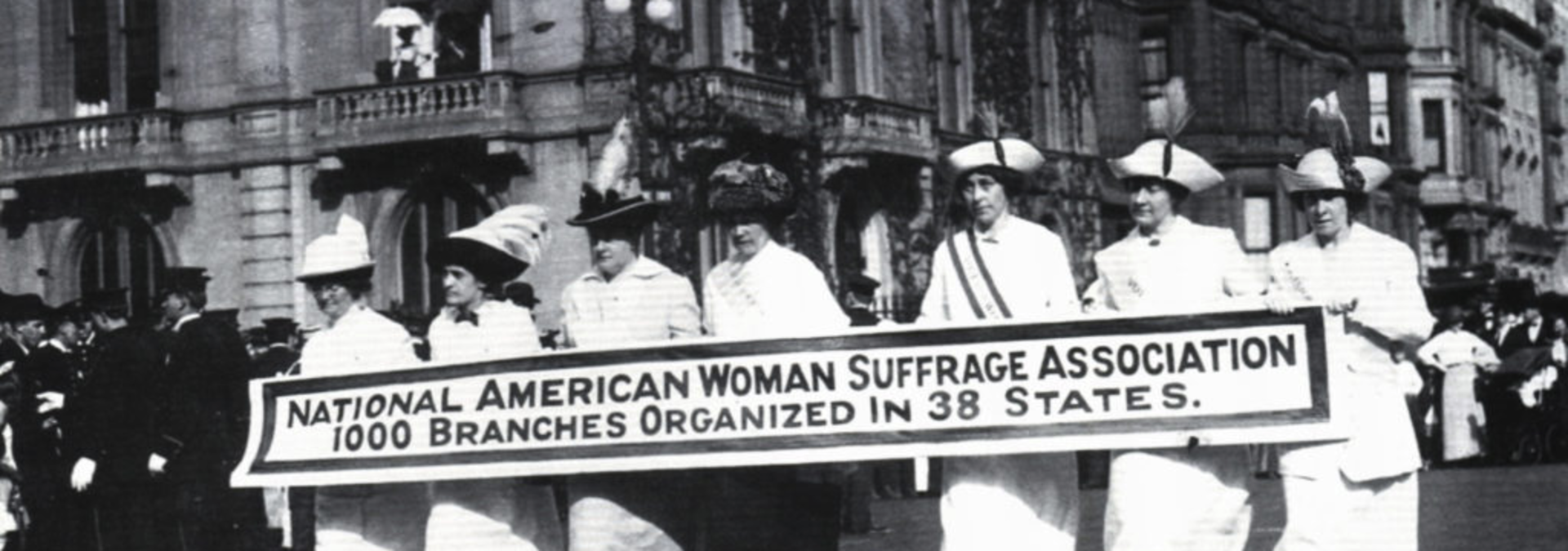

After tireless years of working to promote ideas of women’s suffrage, the two associations put aside their differences (which by then were somewhat moot points, anyway) to join forces and create the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the massive organization’s first president. “By then, the suffragists’ approach had changed. Instead of arguing that women deserved the same rights and responsibilities as men because women and men were ‘created equal,’ the new generation of activists argued that women deserved the vote because they were different from men. They could make their domesticity into a political virtue, using the franchise to create a purer, more moral ‘maternal commonwealth.'” (History.com) This argument gained them new followers from multiple arenas. Advocates of the temperance movement wanted women to have the vote because they believed it would create a cleaner, purer, more chaste country. The middle class enjoyed the idea of introducing homeliness and kindliness into larger, wealthy political parties.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

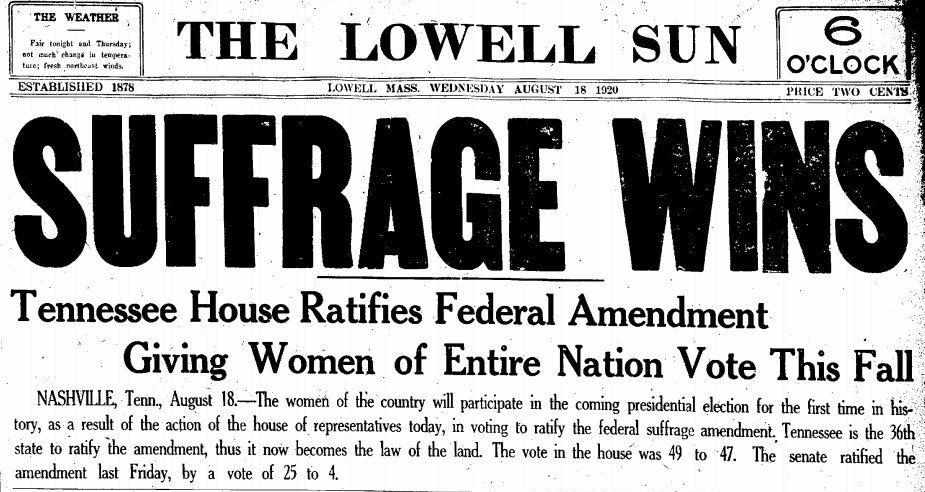

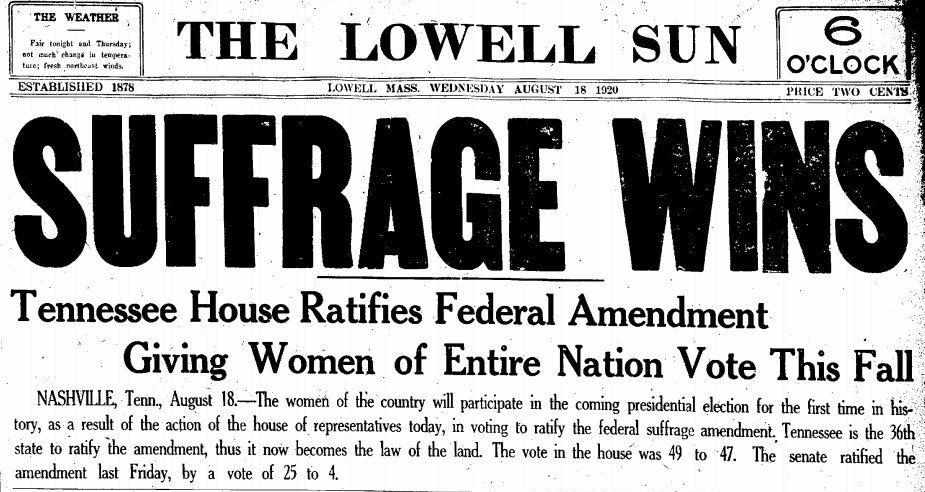

Finally, on August 18, 1920, Tennessee (the last of the 36 states needed to adopt the law) narrowly ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, making voting legal irregardless of sex throughout the United States. A few days later, on August 26th, 1920, 100 years ago today, the Nineteenth Amendment was certified, bringing to culmination an almost 100 year battle by women and men throughout the country. The passing of this amendment enfranchised 26 million American women in time for the 1920 U.S. presidential election. The Amendment states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

We are a far cry away from a perfectly equal country – in terms of race, sex and economy. We still have a mighty hill (or a few) to climb in order to reach Utopia. But one thing we do know… 100 years ago, women had fought tooth and nail for the right to vote. The right to make their voices heard, and the right to assist with change on a national level. They wanted to be seen for who they were, not who they were expected to be, and they wanted more than anything to be taken seriously. In celebrating their great victory, let us not forget what they fought for. An election is upon us, and let’s do them proud. Get out there and VOTE!!!!

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

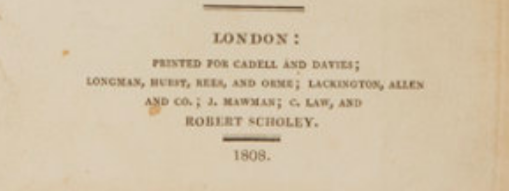

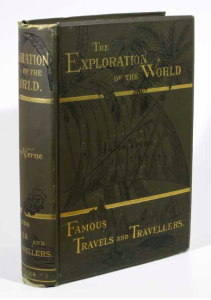

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.  In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

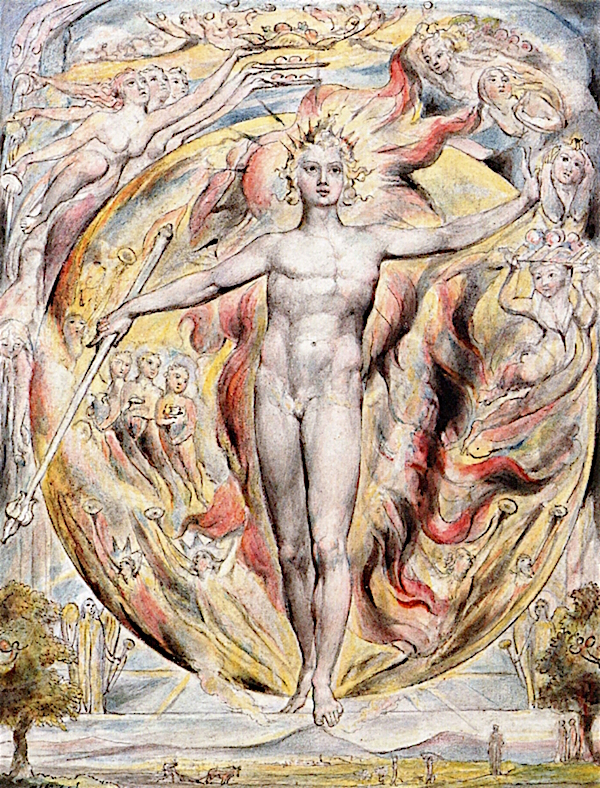

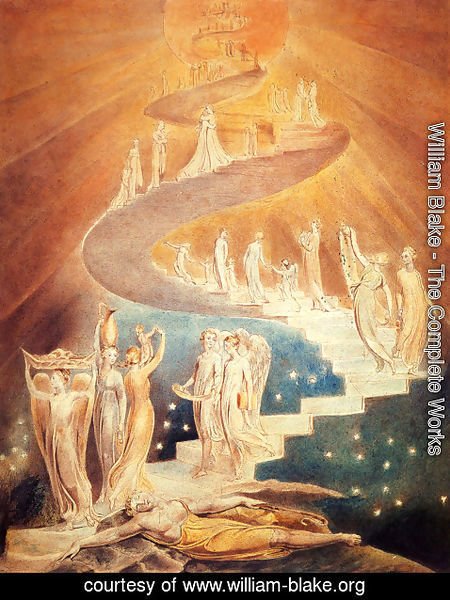

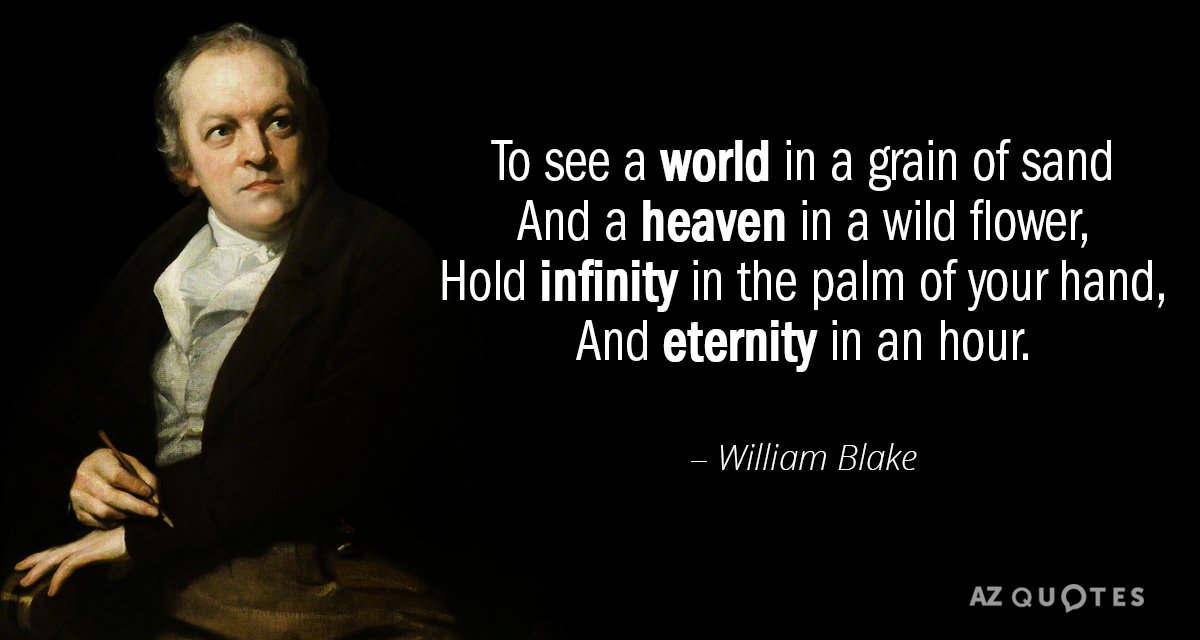

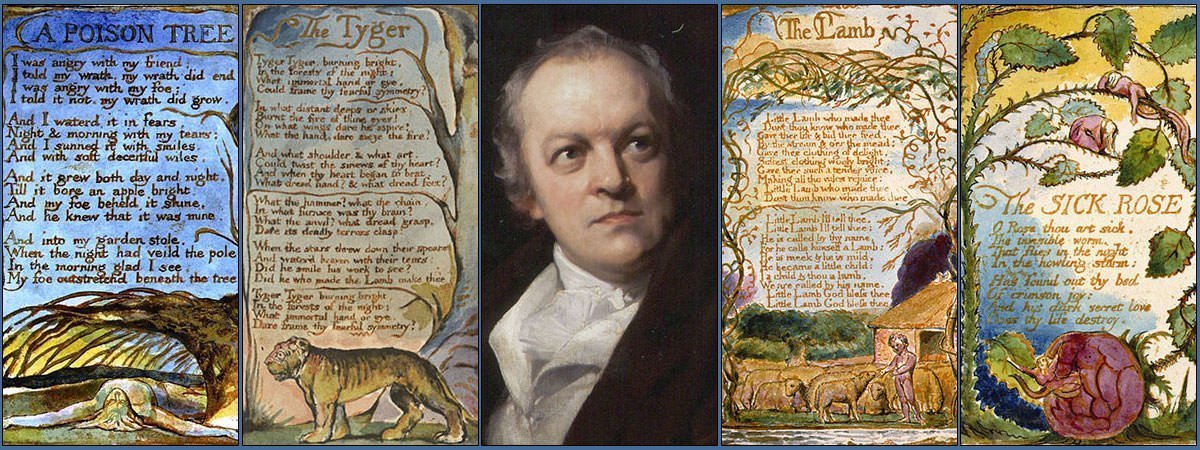

William Blake was born on November 28th, 1757 in Soho, London. He was the third of seven children (though two of his siblings died in infancy). Though his family were English dissenters, it did not stop Blake from being baptized and having a thorough biblical education – knowledge which would prove to be quite inspirational in his work later in life. Blake’s artistic side surfaced when he began copying drawings of Greek antiquities given to him by his father. It was through these copies that Blake was first introduced to works by Michelangelo, Durer and Raphael. By the time Blake was ten he had completed his formal education and was able to be sent to a drawing school in The Strand – where he not only read and avidly studied the arts but also made his first foray into poetry.

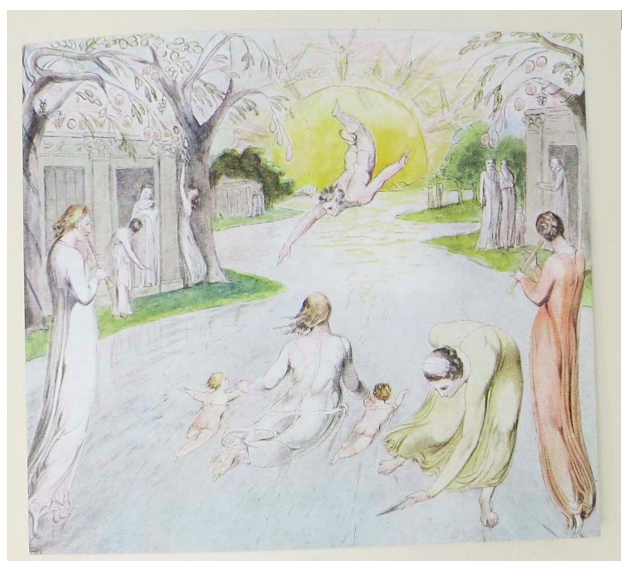

William Blake was born on November 28th, 1757 in Soho, London. He was the third of seven children (though two of his siblings died in infancy). Though his family were English dissenters, it did not stop Blake from being baptized and having a thorough biblical education – knowledge which would prove to be quite inspirational in his work later in life. Blake’s artistic side surfaced when he began copying drawings of Greek antiquities given to him by his father. It was through these copies that Blake was first introduced to works by Michelangelo, Durer and Raphael. By the time Blake was ten he had completed his formal education and was able to be sent to a drawing school in The Strand – where he not only read and avidly studied the arts but also made his first foray into poetry. At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver in London and upon his completion of his apprenticeship became a professional engraver at twenty-one. The following year, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy where he studied over the years and submitted works for exhibition. Though he disagreed with the views held by the headmaster of the time and favored more classical art rather than the popular oil paintings of the age, Blake used the years to make friends in the art world and perfect his own skills. He printed and published his first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, around 1783, and opened up his print shop with fellow apprentice James Parker in 1784. Blake began to associate with radical thinkers of the time – scientists, philosophers and early feminist icons like Joseph Priestly and Mary Wollstonecraft. Blake spent the 80s experimenting with different kinds of printing, finally moving onto relief etching in 1788. Relief etching (also called illuminated printing) would be a medium Blake would continue to use in printing his works throughout his life. In this medium, color illustrations were able to be printed alongside text. Blake has become well-known for his illuminated printing, but throughout his life he was also known for his intaglio engraving – a more standard process of engraving at the time.

At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver in London and upon his completion of his apprenticeship became a professional engraver at twenty-one. The following year, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy where he studied over the years and submitted works for exhibition. Though he disagreed with the views held by the headmaster of the time and favored more classical art rather than the popular oil paintings of the age, Blake used the years to make friends in the art world and perfect his own skills. He printed and published his first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, around 1783, and opened up his print shop with fellow apprentice James Parker in 1784. Blake began to associate with radical thinkers of the time – scientists, philosophers and early feminist icons like Joseph Priestly and Mary Wollstonecraft. Blake spent the 80s experimenting with different kinds of printing, finally moving onto relief etching in 1788. Relief etching (also called illuminated printing) would be a medium Blake would continue to use in printing his works throughout his life. In this medium, color illustrations were able to be printed alongside text. Blake has become well-known for his illuminated printing, but throughout his life he was also known for his intaglio engraving – a more standard process of engraving at the time.