Halloween. There can hardly be a more interesting holiday to research, and, in honor of this coming Friday, research it we certainly have done! The deep traditions underlying “All Hallows’ Eve”, the mutations of those traditions over time, and, naturally, the literature following the course of the holiday over the past few hundred years… all of these factors have made for an extremely interesting study of Halloween. This holiday, which is observed (in many different ways) all over the world in some form or fashion, has a history as diverse as the many cultures which celebrate it today.

The History of Hallowe’en (Condensed)

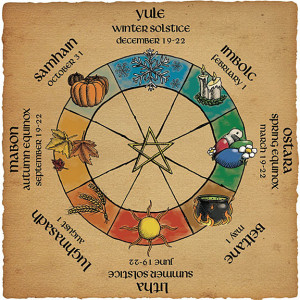

Samhain was celebrated on October 31st, as the Celts observed the end of the harvest season and beginning of the dark & bare winter.

Halloween, as we currently celebrate it, is an eclectic mix of holidays. Its main influences are the Celtic “Samhain” harvest festival, and the Christian “All Hallows’ Day” or “All Saints Day”. The influences of the Celtic harvest festivals are undeniable – as Samhain was viewed as a liminal time, when fairies and spirits could be transported to “our” world and walk amongst the living. These spirits were welcomed home with candles, feasts, dances and offerings. The Christian influence on the holiday came later, when, in 835 A.D., Pope Gregory IV changed the celebration of All Saints Day from May 13th to November 1st, the same day as the Celtic celebration. There are many assumed reasons for this change, some of which may be attributed to Celtic influence, but also for practical reasons – too many pilgrimages made to the Vatican in the summer months, etc. By changing All Hallows’ Day (and All Saints’ Day) to October 31st & November 1st, the Pope effectively gave even more popularity to this end-of-the-season festival established to highlight the beginning of winter.

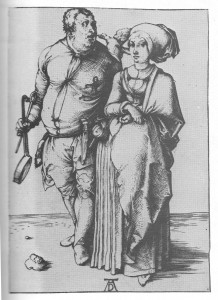

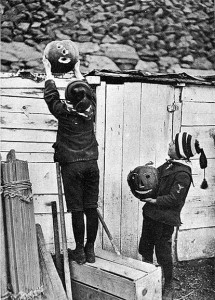

Quite a few Halloween traditions spread from this merging of the festivals. As Christians viewed All Hallows’ Eve as a time allowing the recently departed a chance to extract revenge on their enemies before advancing to the next world, a tradition of disguise was born. Christened folk dressed up in masks and costume in order to confuse the dead – to give themselves safety against any possible revenge by those seeking vengeance. In the Middle Ages the tradition of “souling” came about, where people (particularly children, and often in disguises) went door to door, parish to parish, to beg for “soul cakes” in exchange for praying for the dead relatives of the rich they begged from – the origin of modern day trick-or-treating was born.

After all, Halloween isn’t Halloween without a Jack-O-Lantern to scare away the evil spirits! (Ca. early 20th c.).

The first history on the holiday printed in the United States was Ruth Edna Kelley’s The Book of Hallowe’en, published in Massachusetts in 1919. The author, using Robert Burns’ famous poem Hallowe’en as a guide (a poem internationally regarded as one of the most historically significant works on the holiday, published in Scotland in 1786), stated that “in short, no custom that was once honored at Hallowe’en is out of fashion now.” Almost a century later, this statement still holds true, as disguising ourselves, begging door to door, and celebrating are still popular today (though we are not sure how many people know why they are doing such strange acts on this day of the year).

Scottish and Irish influence truly made the holiday into what it is today, as their Celtic ancestry but staunch Roman Catholicism merged into the collaborative holiday that we know today. Despite the Puritanical influence on early America, and their dislike of holiday celebrations of almost any kind, the influx of Scottish and Irish immigration in the 19th century dramatically increased the holiday’s popularity in the United States (a popularity which has only increased ever since).

Gothic Fiction in the Romantic Period & Halloween in Literature

“The Nightmare”, a 1781 oil-painting by Swiss-Anglo artist Henry Fuseli. This painting gained instant popularity at the beginning of the Gothic literary movement.

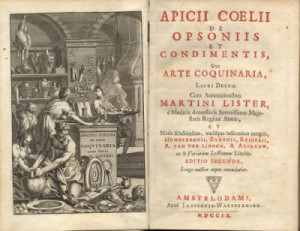

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the human race seems to like to scare themselves silly. The abundance of horror films in modern society and the popularity of said films are proof of the hold that “terror” has on the general public. It is an amazing concept, to willingly give a piece of art (be it a movie, a book, or a photograph) the ability to terrify a human being. This is not a recent notion, however. It is no mere coincidence that gothic and “scary” fiction has reigned supreme since the 1700s when its popularity first emerged. Gothic fiction by popular 18th century writers like Ann Radcliffe and Matthew Lewis (authors of The Romance of the Forest [1791] and The Monk [1796], respectively) helped pave the way for titles such as Frankenstein (1818), The Vampyre (1819), all works of Edgar Allen Poe (early to mid 19th century), Carmilla (1871), The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) and Dracula (1897) to be widely read and devoured by a blood-thirsty public throughout the 1800s. The Victorian period saw a great rise of interest in the supernatural, as evidenced by the popular fiction, but also by the shift of society to an industrial world, which made civilians long for the simple days of old. “The world’s first industrial societies came to hunger for the country… Halloween, as imagined by Victorians – rural, rudimentary, and demanding a certain amount of innocence – was entrancing” (A Halloween Reader by Lesley Bannatyne).

As to Halloween (or simply the dark and unnatural) in American Literature, there are quite a few early works that, when compared to the Halloween celebrated today, exemplifies this shift in belief of Halloween as a waste of time or a hoax to a romanticized, idyllic pastime entrenched in tradition and history. In fact, “The Disappointment” – what is considered to be America’s first opera, performed in 1767 – tells the story of a conjurer duping four Pennsylvania colony folk into believing that he has a magic rod cut on All Hallows’ Eve that will lead the four to pirate treasure. The Halloween reference is placed significantly – to prove the gullibility of the four travelers. Early America saw Halloween as a code word for scam, a time for tricksters and frauds to cheat the public. However, by the end of the 19th century, America was beginning to see the Halloween we were always meant to see – a time for celebration, for honoring the dead, and for being glad to be alive.

This Halloween, as you put on your fishnet stockings or cover your face with a mask guaranteed to terrify the neighbor’s kids, just remember to give a respectful nod to your ancestors and deceased friends or family – as it was for them that this celebration of life was created!