What would be the roughest conditions you could see yourself surviving in? Deserted tropical island in a ‘Cast Away’ situation? Or what about lost in a forest with only a tent and a few cans of beans? I’ve got it! What about trapped in packed ice 720 nautical miles from civilization only to have your boat sink and then have to camp the rest of the time on the ice itself? Could you survive it? Personally, being from Florida, and though I like the occasional cold weather… I can imagine few ways of how I would die faster than being trapped on ice for a year and a half.

That being said, an entire group of men once did it. An explorer and his crew lived on packed ice for months and months… and then some traveled hundreds of miles for help and rescue. Ernest Shackleton is a name known by adventure enthusiasts, explorer aficionados and travel collectors across the world.

Ernest was born in February 1874 in County Kildare, Ireland – the first of two boys out of ten children in an Anglo-Irish family… and the son of a dreamer. When Ernest was six his father gave up his career as a landowner and decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He moved the family to Dublin in order to begin his studies at Trinity College. Once acquiring his degree, Henry Shackleton then moved his family to London when Ernest was 10. Shackleton was an avid reader, but a maddening student. He did not take to lessons so well, despite being able to finish at the top of his class several years, and was finally allowed to leave school at 16 to pursue the adventures he had dreamed of for years while reading travel books and thrilling adventure accounts. His father got him an apprenticeship on a sailing vessel, and the young Shackleton spent the next 8 years studying for different mariner tests, Second Mate, then First Mate, and ultimately Master Mariner (captain).

Ernest was born in February 1874 in County Kildare, Ireland – the first of two boys out of ten children in an Anglo-Irish family… and the son of a dreamer. When Ernest was six his father gave up his career as a landowner and decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He moved the family to Dublin in order to begin his studies at Trinity College. Once acquiring his degree, Henry Shackleton then moved his family to London when Ernest was 10. Shackleton was an avid reader, but a maddening student. He did not take to lessons so well, despite being able to finish at the top of his class several years, and was finally allowed to leave school at 16 to pursue the adventures he had dreamed of for years while reading travel books and thrilling adventure accounts. His father got him an apprenticeship on a sailing vessel, and the young Shackleton spent the next 8 years studying for different mariner tests, Second Mate, then First Mate, and ultimately Master Mariner (captain).

In 1901, Shackleton took a job on the National Antarctic Expedition, also known as the Discovery Expedition (after the ship it was on… the Discovery) led by Robert Falcon Scott on a mission of scientific study and geographical mapping. The ship was strictly run, with Scott following Royal Naval protocol. Through this Shackleton discovered he preferred a slightly more casual and easy-going approach to management. The journey taught Shackleton much about leadership, and also about problems encountered on both water and land voyages, Shackleton himself at one point falling ill with scurvy. However, Shackleton was also one of the most popular members on board the ship, and though his weakened system at the end of his voyage with the Discovery was definitely cause for alarm and the reasoning behind him being sent home on a relief ship, there are those who contest that his undeniable popularity among the crew made Captain Scott jealous and he was sent home for resentful reasons. In any case, it was an invaluable learning experience for Shackleton.

In 1908 Shackleton led his own Antarctic expedition, finally captain of his own ship, the Nimrod. He and a small crew climbed Mount Erebus (the first time ascent on record) and set a record for the closest anyone had ever been to the South Pole. He and his small expedition team almost met with starvation making their way back to the ship, with the ever-popular Shackleton giving up his own measly rations to another failing crew member, Frank Wild, who would later write about that moment in his diary, “All the money that was ever minted would not have bought that biscuit and the remembrance of that sacrifice will never leave me.” The grateful Wild would later become the second in command on Shackleton’s larger expedition in 1914. Upon his return to the UK after his experiences on the Nimrod, Shackleton was knighted and awarded a Gold Medal by the Royal Geographical Society. Fun fact: Shackleton and his crew left several cases of whiskey and brandy behind in the Antarctic in 1909, and the cases were found in 2010 and analyzed! “A revival of the vintage (and since lost) formula for the particular brands found [was] offered for sale with a portion of the proceeds [going] to benefit the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust.” Awesome!

After several years of public appearances and lectures, Shackleton was once more ready for a voyage in 1914. He titled his journey the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition”, and it would take 2 ships to either side of Antarctica so that he might cross part of the continent (1,800 miles of it) with a team of six other men. Shackleton received 5,000+ applications to join his crew, and in being selective on personality and disposition he selected 56 men to populate the two ships. Shackleton would be captaining the Endurance and the Aurora would meet him at the end of his journey across the ice.

The Endurance began it’s slow and hard journey through the Weddell Sea in early December, by mid-January becoming frozen in first year ice. Shackleton realized at the end of February that the boat would be stuck until the following spring (that October or thereabouts, as the seasons are backwards), as there was no hope for the ice to thaw in such conditions. Shackleton ordered the men to abandon the ship and begin setup of a camp on the packed ice, thankfully, as despite Shackleton’s hope that the boat would break free of the ice come spring and be able to continue sailing, the pressure put on the boat the following September from the breaking of the ice ended up sinking (albeit slowly) the then abandoned ship. For about two months Shackleton and his crew camped on flat ice floes, changing from floe to floe hoping one might drift them down to the inhabited Paulet Island. Unfortunately they were unable to reach it and using their lifeboats they were eventually able to make it to Elephant Island – that being the first time they had stood on dry land in over a year. Shackleton kept a watchful eye on all of his men, as usual, and in giving his mittens to his photographer Frank Hurley suffered from frostbite himself.

The Endurance began it’s slow and hard journey through the Weddell Sea in early December, by mid-January becoming frozen in first year ice. Shackleton realized at the end of February that the boat would be stuck until the following spring (that October or thereabouts, as the seasons are backwards), as there was no hope for the ice to thaw in such conditions. Shackleton ordered the men to abandon the ship and begin setup of a camp on the packed ice, thankfully, as despite Shackleton’s hope that the boat would break free of the ice come spring and be able to continue sailing, the pressure put on the boat the following September from the breaking of the ice ended up sinking (albeit slowly) the then abandoned ship. For about two months Shackleton and his crew camped on flat ice floes, changing from floe to floe hoping one might drift them down to the inhabited Paulet Island. Unfortunately they were unable to reach it and using their lifeboats they were eventually able to make it to Elephant Island – that being the first time they had stood on dry land in over a year. Shackleton kept a watchful eye on all of his men, as usual, and in giving his mittens to his photographer Frank Hurley suffered from frostbite himself.

Shackleton then took five men and used a lifeboat to travel over 800 miles to a whaling station in South Georgia to get help. He would only pack four weeks of supplies into the lifeboat, knowing that if they could not reach their destination within a months time that they might as well consider themselves lost – he did not want to take supplies away from the men remaining on Elephant Island. Within 15 days they saw South Georgia, but inhospitable weather did not allow them to land immediately. When they were able to reach shore they had to pull up on the south side of the island, unfortunately knowing the whaling station was on the north side. Rather than get back in the lifeboat, three of the crew decided to attempt the journey across the mountainous land on foot – a distance of 32 miles (these guys couldn’t seem to catch a break, am I right?). They fastened screws into their boots to act as climbing shoes and had 50 feet of rope between the three of them. Not an easy journey… but they finally made it to the whaling station and got the help they needed. With the help of a Chilean vessel, Shackleton reached the rest of his 22 men on Elephant Island on the 30th of August, 1916 – 101 years ago today. After over a year and a half ordeal living on ice, every single man aboard the Endurance and under Shackleton’s command made it back alive. If Shackleton hadn’t already been considered a hero – he certainly was then!

Shackleton then took five men and used a lifeboat to travel over 800 miles to a whaling station in South Georgia to get help. He would only pack four weeks of supplies into the lifeboat, knowing that if they could not reach their destination within a months time that they might as well consider themselves lost – he did not want to take supplies away from the men remaining on Elephant Island. Within 15 days they saw South Georgia, but inhospitable weather did not allow them to land immediately. When they were able to reach shore they had to pull up on the south side of the island, unfortunately knowing the whaling station was on the north side. Rather than get back in the lifeboat, three of the crew decided to attempt the journey across the mountainous land on foot – a distance of 32 miles (these guys couldn’t seem to catch a break, am I right?). They fastened screws into their boots to act as climbing shoes and had 50 feet of rope between the three of them. Not an easy journey… but they finally made it to the whaling station and got the help they needed. With the help of a Chilean vessel, Shackleton reached the rest of his 22 men on Elephant Island on the 30th of August, 1916 – 101 years ago today. After over a year and a half ordeal living on ice, every single man aboard the Endurance and under Shackleton’s command made it back alive. If Shackleton hadn’t already been considered a hero – he certainly was then!

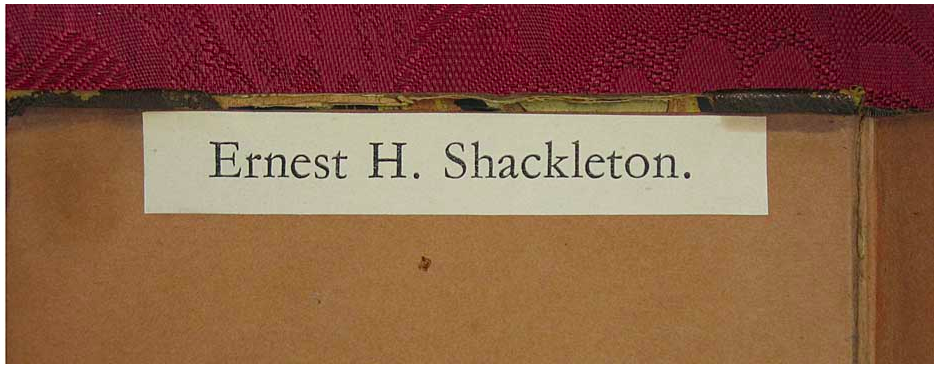

Today we honor the bravery shown by Shackleton and his crew, and feel the gratefulness these men must have felt upon their rescue! And now, for a bit of antiquarian book world pleasure… check out this 1843 Dickens edition of Master Timothy’s Book-Case… previously owned by one Ernest H. Shackleton! Enjoy.

Today we honor the bravery shown by Shackleton and his crew, and feel the gratefulness these men must have felt upon their rescue! And now, for a bit of antiquarian book world pleasure… check out this 1843 Dickens edition of Master Timothy’s Book-Case… previously owned by one Ernest H. Shackleton! Enjoy.