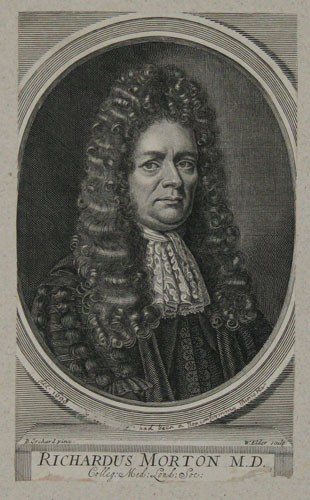

The history of medicine is rich with fascinating stories and personalities. One of these was Richard Morton, an ousted minister who turned to medicine as a second career. The source of Morton’s medical education remains somewhat mysterious, but he nevertheless managed to distinguish himself in the profession, even rising to be the physician-in-ordinary to the king. Today Morton is remembered primarily for his contribution to the study of phthisis, more commonly known today as pulmonary tuberculosis.

Eight Missing Years of Medical Training?

The son of a minister, Morton was baptized in 1637. As a young man he resolved to follow in his father’s footsteps, and after earning a BA at Oxford took a position as the Vicar of Kinver at Staffordshire. The post was a comfortable one, and Morton would likely have remained in it indefinitely–were it not for the  Restoration. A dissenter, Morton could not comply with the requirements of the Act of Uniformity. In 1662 he was ousted from his living and forbidden from reentering the ministry, along with 2,000 other ministers would could not give “unfeigned consent and assent” to everything contained in the Prayer Book.

Restoration. A dissenter, Morton could not comply with the requirements of the Act of Uniformity. In 1662 he was ousted from his living and forbidden from reentering the ministry, along with 2,000 other ministers would could not give “unfeigned consent and assent” to everything contained in the Prayer Book.

For the next eight years, there is no record of Morton’s activities. Scholars guess that he went to Holland to study at the University of Leyden, which was then the most famous medical university in Europe. Morton’s expertise in phthisis would suggest that he studied under Silvius, the leading medical professor at the University of Leyden. And his subsequent patronage from Prince William of Orange also suggests a strong connection to the Netherlands.

The fact that there are no records of Morton’s medical training have led some experts to postulate that Morton was entirely self-taught. Indeed many clergymen of the era taught themselves medicine to serve their congregants. Meanwhile, Morton also mentions, “My dear Father, who was himself a very skilful Physician.” It’s possible that Morton first discovered medicine through the books in his father’s library and, being interested in the subject, turned to medicine when the ministry was no longer an option. But his advanced knowledge of anatomy simply could not have been acquired in books.

Wherever Morton got his training, he had no trouble establishing a practice in London in 1670. Here, he had some help from Prince William of Orange, who nominated him for a medical degree from Oxford. William attended Morton’s nomination ceremony while visiting England to collect on a debt owed by Charles II. By 1670, Morton had established his own practice in London. Only eight years later, Morton was elected a Fellow in the Royal College of Physicians.

In 1686, Morton’s politics again got him into a bit of trouble: his was one of four names omitted from the list of renewals to the College charter. James II thought that Morton might be politically unreliable because he’d accepted patronage from William of Orange. Morton was barred from participating in College activities and debates for the next three years. But with the accession of William and Mary in 1689, Morton was restored to the Fellowship and eventually rose to the rank of physician-in-ordinary to the king.

A Landmark Publication in Medical History

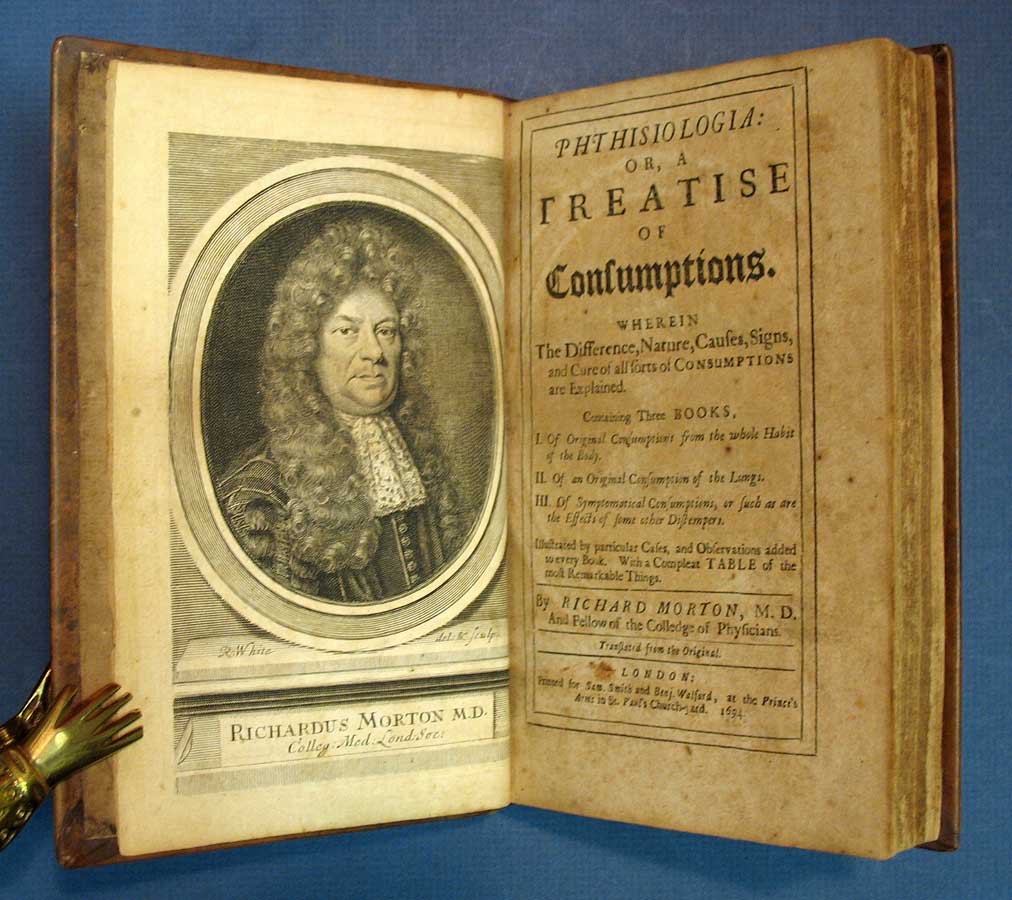

But it’s for his Phthisiologica that Morton is remembered in the history of medicine. The book, dedicated to William of Orange, was perhaps inspired by William’s own respiratory problems. When the book was first published in London in 1689, it was presented in Latin. The first English edition appeared in 1694, with at least two subsequent editions in 1719 and 1720. Multiple continental editions followed in Frankfurt (1690); Ulm (1714); and Helmstad (1780). Thus Phthisiologica maintained prominence for about a century.

Morton was certainly not the first to address phthisis, which at the time was defined rather broadly as any wasting disease (and is now defined only as pulmonary tuberculosis, mainly because our powers of differential diagnosis are superior). In seventeenth-century England, tuberculosis always loomed a specter. John Locke addressed the illness in De Phthysi (1685) and estimated that the ailment caused about 20% of the deaths in England.

Before Locke, Christopher Bennett (1617-1655) had explored phthisis, though his explanations for the disease were hardly based on facts. Bennett suffered from phthisis himself and argued that this fact made him the authority on the condition. But many of his statements were anecdotal, and he frequently ignored evidence that contradicted his claims. Next was Thomas Willis (1617-1675). Willis was appointed Sedlian Professor of Natural Philosophy at Oxford in June 1660. His Practice of Physick, published posthumously, included an entire chapter on phthisis. And Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) illustrates how little seventeenth-century physicians really knew. He enthusiastically advocated horseback riding as a treatment for phthisis.

What set Morton apart from his predecessors and contemporaries, at least in terms of diagnostic observation, is that Morton presented evidence that lungs affected by phthisis would often have both ulcers and tubercles. He saw these tubercles as glandular parts that were ordinarily too small to be detected with the naked eye, and which grew inflamed with infection. Such an observation could be made only through post-mortem observation of patients who had died of phthisis. The idea of desecrating a body in such a way was hardly popular at the time. It was common practice in Europe–and later in the United States–to threaten dissection as punishment for wrongdoing, as a punishment even worse than death.

Another fascinating aspect of Phthisiologia is that it contains virtually no references to other medical texts. Though Morton incorporates a few aphorisms of Hippocrates, he doesn’t allude to any pre-existing or contemporary medical theory. It’s clear that his conclusions are all drawn from his own firsthand observations and experiences. Morton’s case studies demonstrate that he was an able physician, especially given the lack of medical tools and knowledge available at the time. His work even predates Auenbrugger’s discovery of percussion as a diagnostic tool. Thus Morton worked only with his own power of clinical observation and deduction, along with the occasional palpation.

Richard Morton’s Phthisiologia is truly a seminal work in the histories of science and medical literature. Though Morton obscured the antecedents of his medical knowledge, he left behind a work that perfectly captures both his own aptitude as a physician and the contemporary approach to medical practice.

Related Posts:

Elias Samuel Cooper: Renowned and Controversial Surgeon

Edith Cavell, Nurse, Humanitarian, and Traitor?

Famous Figures in the History of Nursing (Part One)

Famous Figures in the History of Nursing (Part Two)

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.