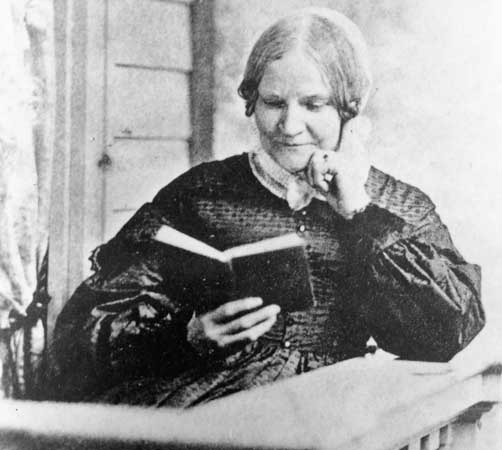

Lydia Maria Francis Child established herself as a respected novelist before her rational approach to abolitionism cost her career. An influential thinker, Child managed to rebuild her reputation and became one of the most respected abolitionists of the time.

Child was born on February 11, 1802 in Medford, Massachusetts. Her father, David Convers Francis, was a successful businessman and sent her older brother, Convers, to Harvard. The same educational opportunity was not available to Child, but Convers supervised her education. When Child’s mother died in 1814, she was sent to live with her sister Mary Francis Preston in Norridgewock, Maine Territory. Child would stay there until 1820 and study at the local academy, which Convers supplemented with the works of Milton, Homer, and other classics.

In 1821, Child moved back to Massachusetts to live with Convers, who was by now a minister at the Unitarian church in Watertown. Just outside of Boston, Watertown was a veritable hotbed for progressive thought, and it was there that Child met such illustrious figures as John Greenleaf Whittier, Theodore Parker, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Child also befriended Margaret Fuller.

By this time, Child had opened up her own girls’ school, but she still found time to write her first novel. Hobonok, a Tale of the Times (1824) was published when Child was only 22 years old. It recounted the story of Mary Conant, who is forbidden to marry her Episcopalian lover. Instead, she marries Hobonok, a member of the Pequod tribe and bears his child. While the literary community found the book scandalous, the novel became quite popular. Encouraged, Child published The Rebels; or, Boston Before the Revolution (1825), a novel about the events leading up to the Boston Tea Party. This book was popular among critics and readers alike.

In 1826, Child started Juvenile Miscellany, the first periodical in the United States that was solely devoted to children. She filled the journal with her own poems and stories, along with plenty of educational material. The venture proved more profitable than Child had anticipated, and it provided her a nice living for the next eight years.

Child met David Lee Child in 1828. He was a Harvard educated lawyer who practiced in Boston and had served in the state legislature. He also edited the Massachusetts Whig Journal. The couple soon married, and David introduced his wife to a new side of issues like Indian rights and abolition, including the radical ideas of William Lloyd Garrison.

Despite David’s education and credentials, he proved a poor breadwinner. Child supported them both with her writing. In 1829, she published The Frugal Housewife. The manual included tips on saving money, preparing home remedies, and educating girls. The book proved a success, and Child followed up with The Mother’s Book and The Little Girl’s Own Book in 1831. These volumes earned Child international renown.

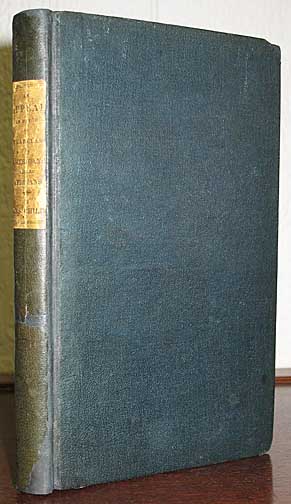

In 1833, Child made a decidedly bold move. She published An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans. The abolitionist book represented a significant departure from abolitionist literature of the era: rather than making religious or scriptural arguments, Child appeals to reason and makes a political case for abolition. Child also went a step further than most abolitionists, presenting a case not just for eliminating slavery, but also for ending discrimination against freed African Americans. Child advocated immediate emancipation–without compensating slave owners for their “lost property” and spoke out against the colonization of Africa. The book is considered a tour-de-force in abolitionist literature, and it influenced leaders like Wendell Phillips, William Ellery Channing, and Charles Sumner.

In 1833, Child made a decidedly bold move. She published An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans. The abolitionist book represented a significant departure from abolitionist literature of the era: rather than making religious or scriptural arguments, Child appeals to reason and makes a political case for abolition. Child also went a step further than most abolitionists, presenting a case not just for eliminating slavery, but also for ending discrimination against freed African Americans. Child advocated immediate emancipation–without compensating slave owners for their “lost property” and spoke out against the colonization of Africa. The book is considered a tour-de-force in abolitionist literature, and it influenced leaders like Wendell Phillips, William Ellery Channing, and Charles Sumner.

Child faced immediate repercussions for her Appeal. The Boston Athenaeum revoked her free reading privileges. Book sales plummeted. People rushed to cancel their subscriptions to Juvenile Miscellany, and Child was forced to shut it down. Meanwhile her husband had opted to raise sugar beets instead of slave-produced sugar cane, which was a complete failure. Their savings slowly dwindled.

In 1841, Child accepted editorship of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, the New York newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society. But she couldn’t agree with the use of violence and other extreme measures to further the cause and left the publication in 1843. Her departure caused a significant rift in the abolition movement. Her husband stepped up as editor after her, but was equally unable to stomach the society’s agenda.

That year, Child separated her finances from her husband’s, and the couple would remain estranged for a decade. Child turned to journalism to support herself, writing prolifically for newspapers and other periodicals. With Letters from New York (1843-1845), she managed to reestablish her reputation as an author. Child also took up the cause of gender equality, but she was reluctant to officially align herself with either suffrage or abolitionist movements after her break with the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Child and her husband reconciled in 1852 and moved to Weyland, Massachusetts. Though they were no longer at the center of public affairs, they nevertheless stayed engaged. The couple sheltered runaway slaves in their home and closely followed the affair of their good friend Charles Sumner. Senator Preston Brooks had caned Sumner senseless for his “Crime Against Kansas” speech, and Sumner retaliated with a poem called “The Kansas Emigrants.”

When John Brown staged his rebellion at Harper’s Ferry in 1859, Child was compelled to action. Though she didn’t agree with Brown’s violent approach, she admired his courage. When Child learned that Brown had been injured, she immediately wrote to Virginia Governor Henry Wise to offer her nursing services at Brown’s bedside.

Brown declined the offer, but it nevertheless rankled the pro-slavery camp. Mrs. James Mason, the wife of the author of the Fugitive Slave Act, stepped in. She, too, wrote to Governor Wise, denouncing Child for offering her services to a murderer. Mason made an ill-advised appeal, noting that Southern women aided slave women during child birth. Child immediately responded, pointing out that Northern women, too, assisted in the childbirth of African Americans, but “after we have helped the mothers, we don’t sell the babies.” The Child-Wise-Mason correspondence was packaged as a pamphlet by abolitionist leaders and distributed all over the North. At one point, 30,000 copies were circulating.

Thus ironically it was the same outspoken abolitionism that had cost Child her reputation that would again make her a celebrated figure. Child continued to speak for equal treatment of African Americans. In 1861, she gladly accepted an invitation to edit former slave Harriet Jacob’s novel Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. She followed in 1865 with The Freedman’s Book, a collection of sketches, poetry, and essays designed to be inspirational to newly freed blacks. Child’s last publication would be an anthologies of her works, Aspirations of the World: A Chain of Opals (1878).

Child passed away on October 20, 1880. A central figure in the abolitionist movement, her works are considered highly collectible by both historians and literature lovers alike.