The early English Quaker movement emerged in the wake of King Charles I’s regicide, between the English Civil Wars and the Restoration. Multiple sects emerged between 1640 and 1660, and the word “Quaker” had yet to have a definitive meaning; in the media, the word was applied to people with quite divergent beliefs. Even among people who called themselves Quakers, views greatly varied. For instance, George Fox believed in the “Dwelling Spirit.” Meanwhile, a militant wing of the group advocated the use of violence to achieve its goals for the Second Coming and even attempted to assassinate Oliver Cromwell.

Following Venner’s Uprising in 1660, King Charles II and his government kept a close eye on the Quakers; the group had demonstrated its volatility, and some members were even suspected of murdering King Charles I. The king urged moderate Quakers to subdue its more radical members. The result: the group turned more of its attention to addressing England’s social problems, returning to its English Seeker roots. Meanwhile, the group increasingly turned to the pen, rather than the sword. Thus the history of the Quakers is one that we can trace through a rich body of literature, written by some of the sect’s most prominent (and sometimes controversial) figures.

George Whitehead

Born in Westmoreland, George Whitehead discovered the Quaker philosophy at age fourteen. He began preaching in a limited capacity only two years later. Shortly thereafter, Whitehead joined the Valiant Sixty, a group of itinerant preachers that started in northern England and gradually traveled south. He was one of the group’s youngest members: only he, James Parnell (age 16) and Edward Burrough (age 18) joined the group before they were “of age.” The seventeenth century was a time of religious intolerance in England, and the Quakers often had brushes with the law. Whitehead was thrown in jail on multiple occasions and was once publicly whipped. He spoke out against the Act of Uniformity in 1660 and was influential in the Bill of Rights of 1689 and the Royal Declaration of Indulgence.

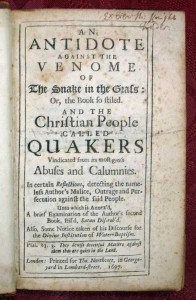

Whitehead published his journal, The Christian Progress of George Whitehead. He also wrote An Antidote Against the Venome of the Snake in the Grass, a rebuttal directed at Irish clergyman Charles Leslie the author of The Snake in the Grass, Satan Disrob’d, and A Discourse Proving the Divine Institution of Water Baptism. Most notably, Whitehead defended women’s ability to preach if they were so inspired, saying “we do not institute Women’s Preaching as [Leslie] saith, but leave them free to the Gift and Call of God.” The volume also includes an early mention of Quakers in America, including William Penn’s Pennsylvania colony. Whitehead’s views ultimately proved too liberal; by the 1800’s, his philosophy and works had passed out of favor in the Quaker community.

Whitehead published his journal, The Christian Progress of George Whitehead. He also wrote An Antidote Against the Venome of the Snake in the Grass, a rebuttal directed at Irish clergyman Charles Leslie the author of The Snake in the Grass, Satan Disrob’d, and A Discourse Proving the Divine Institution of Water Baptism. Most notably, Whitehead defended women’s ability to preach if they were so inspired, saying “we do not institute Women’s Preaching as [Leslie] saith, but leave them free to the Gift and Call of God.” The volume also includes an early mention of Quakers in America, including William Penn’s Pennsylvania colony. Whitehead’s views ultimately proved too liberal; by the 1800’s, his philosophy and works had passed out of favor in the Quaker community.

Elias Hicks

Born in Hempstead, New York in 1748, Elias Hicks was a carpenter who became a Quaker in his early twenties. In 1778, Hicks helped to construct the Friends Meeting House in Jericho, New York, where he’d settled with his wife. By this time, Hicks was already preaching extensively. That same years, Walt Whitman heard Hicks preach at Morrison’s Hotel in Brooklyn. The famed poet, then still quite young, would later recall the preacher’s “resonant, grave, melodious voice.”

In 1799, Hicks and his neighbor Phebe Dodge manumitted their slaves. They were the first Quakers to do so in their community, and soon after all the families of Westbury meeting had followed suit. Hicks also campaigned for a boycott of all goods produced by slaves, which mostly included cotton and products that contained sugar. In 1811, he wrote Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendants, which outlines the economic reasons for continuing slavery and points to war as a primary cause of slavery. The book gave the free produce movement a firm foundation. Although the movement wasn’t meant to be religious in nature, the majority of its proponents were indeed Quakers. The first person to open a free produce store was Benjamin Lundy, a Quaker who opened up a free produce mercantile in 1826. Lundy advocated helping freed slaves emigrate to Haiti and raising mone to buy slaves and settle them as free citizens in the territories out West. Hicks was a key figure in abolishing slavery in New York.

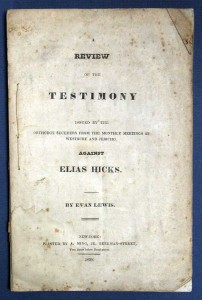

While Hicks’ abolitionism certainly fit with Quaker tenets, the same was not so with his theological stance. Hicks believed that following the “Inner Light” was the most important aspect of worship. He also denied Jesus’ complete divinity and the virgin birth. Furthermore, Hicks argued that the Devil was not at the root of human failings and sin, but that urges were simply part of human nature–and created by God. Thanks to the Great Awakening and other factors, the Quaker community was ripe for a schism, and Hicks’ controversial philosophy provided the reason. Hicks engaged with fellow Quaker Anne Braithewaite in a debate that produced a flurry of publications. Eventually, in 1828, after Hicks actually stood a sort of trial, the Quakers decided a separation was necessary. Those who followed Hicks were mostly rural poor and came to be called Hicksites. His critics called themselves the Orthodox Friends. Each group considered itself to be the rightful bearers of the legacy begun by Friends founder George Fox. The two groups would not be the only factions to develop among the American Quaker community.

While Hicks’ abolitionism certainly fit with Quaker tenets, the same was not so with his theological stance. Hicks believed that following the “Inner Light” was the most important aspect of worship. He also denied Jesus’ complete divinity and the virgin birth. Furthermore, Hicks argued that the Devil was not at the root of human failings and sin, but that urges were simply part of human nature–and created by God. Thanks to the Great Awakening and other factors, the Quaker community was ripe for a schism, and Hicks’ controversial philosophy provided the reason. Hicks engaged with fellow Quaker Anne Braithewaite in a debate that produced a flurry of publications. Eventually, in 1828, after Hicks actually stood a sort of trial, the Quakers decided a separation was necessary. Those who followed Hicks were mostly rural poor and came to be called Hicksites. His critics called themselves the Orthodox Friends. Each group considered itself to be the rightful bearers of the legacy begun by Friends founder George Fox. The two groups would not be the only factions to develop among the American Quaker community.

Joseph John Gurney

Born in 1788, Joseph John Gurney was a banker in Norwich, England. Raised in the Quaker faith, he joined the sect and became an evangelical minister in the Religious Society of Friends. Because he was a member of a non-conformist religious group, Gurney was ineligible to study at English universities, so he was educated by a private tutor at Oxford. Gurney’s sister Elizabeth Fry was a social reformer, and in 1817 the siblings partnered to protest the death penalty and to improve conditions in prisons. They had little success, but Gurney would remain committed to the cause.

Finally Home Secretary Robert Peel introduced the Gaols Act of 1823, which required that wardens be paid salaries–rather than being supported by the prisoners themselves. The Act also placed female wardens in charge of female prisoners and outlawed the use of manacles and irons. Meanwhile, Gurney and Fry visited prisons all over Great Britain. They published their findings in Prisons in Scotland and the North of England.

Finally Home Secretary Robert Peel introduced the Gaols Act of 1823, which required that wardens be paid salaries–rather than being supported by the prisoners themselves. The Act also placed female wardens in charge of female prisoners and outlawed the use of manacles and irons. Meanwhile, Gurney and Fry visited prisons all over Great Britain. They published their findings in Prisons in Scotland and the North of England.

In 1837, Gurney began a journey to America and the West Indies, where he promoted abolitionism. He also preached at local Meeting houses in America and grew concerned about the prevalence of the “Inner Light” philosophy. Gurney felt that the American Quakers did not give sufficient weight to the Bible and the New Testament in their theology. This created a yet another splinter, between those who followed Gurney and those who followed his opponent, John Wilbur. Their respective disciples, predictably enough, were called Gurneyites and Wilburites, respectively.

The literature of the Quakers offers considerable insight into colonial history, and it is full of fascinating personalities who shaped approaches to social issues in the Western World.

Related Posts:

Charles Dickens and Capital Punishment

The California Gold Rush, Slavery, and the Civil War

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.