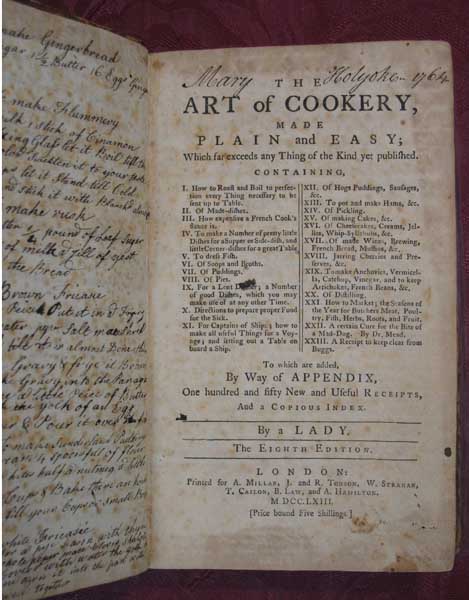

At first, cookbooks were largely written by men. Their intended audience were the individuals who ran restaurants and the households of the wealthy. It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that this trend began to shift. Perhaps the most notable cookbook of the century is Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery (1747), which Glasse wrote for “the lower sort,” that is, domestic servants. Unlike her predecessors, Glasse used a conversational tone and an expository approach that appealed to an incredibly broad audience.

Glasse could not claim all the delicious recipes in The Art of Cookery as her own; she had borrowed thoroughly from other cookbooks. Meanwhile, her own book would be pirated and plagiarized plenty of times. Even during her lifetime, Glasse discovered “new editions” of her book that contained sections she had not even written! Her publishers were to blame for some of that; they wanted to update the book to fit with changing tastes. The tactic worked; The Art of Cookery would become the definitive English cookbook for the remainder of the century, and now the various editions an incredibly thorough representation of the foodways of eighteenth-century Britain.

Glasse could not claim all the delicious recipes in The Art of Cookery as her own; she had borrowed thoroughly from other cookbooks. Meanwhile, her own book would be pirated and plagiarized plenty of times. Even during her lifetime, Glasse discovered “new editions” of her book that contained sections she had not even written! Her publishers were to blame for some of that; they wanted to update the book to fit with changing tastes. The tactic worked; The Art of Cookery would become the definitive English cookbook for the remainder of the century, and now the various editions an incredibly thorough representation of the foodways of eighteenth-century Britain.

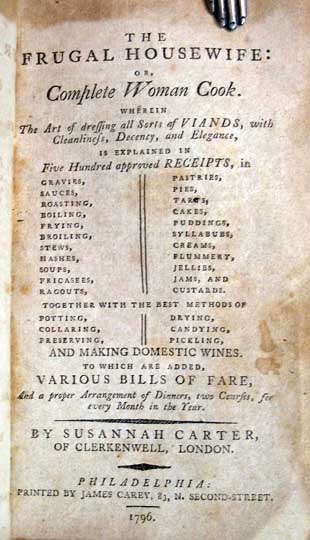

Glasse is undoubtedly a major figure in culinary history, but it was a lesser known personage whose cookbook would successfully “cross the pond” from Britain to the New World. Susannah Carter, author of The Frugal Housewife (c 1765) takes that honor. Carters work was significant because it was overtly aimed at housewives, rather than servants and chefs, and because it was one of the earliest printed American cookbooks–and certainly the most successful.

Unfortunately we know little about Carter, save that she hailed from Clerkenwell, in London. We know much more about the publishing history of The Frugal Housewife, which is interesting unto itself. In London, the book was published by Francis Newbery (the nephew of John Newbery) in the printing enclave near St. Paul’s Cathedral. The same year, the book appeared in Dublin. The Frugal Housewife didn’t make its way to the colonies until 1772. It was published by Benjamin Edes and John Gil and illustrated with prints by Paul Revere. Edes and Gil were known for publishing the works of Revolutionary writers, and they played a significant role in instigating the Boston Tea Party.

As colonial booksellers, Edes and Gil had little bargaining power with British publishers. They desperately needed British titles to stay in business, and they couldn’t offer many interesting colonial works in return. Thus British booksellers would often force their colonial counterparts to buy less desirable works–such as a cookbook–in order to acquire more literary titles.

As colonial booksellers, Edes and Gil had little bargaining power with British publishers. They desperately needed British titles to stay in business, and they couldn’t offer many interesting colonial works in return. Thus British booksellers would often force their colonial counterparts to buy less desirable works–such as a cookbook–in order to acquire more literary titles.

Cookbooks were a burgeoning field at the time, so Newbery may not have predicted that colonial publication of The Frugal Housewife would be profitable. Thus it’s quite possible that Newbery essentially forced the American publication of The Frugal Housewife, unwittingly created something of an American cookery phenomenon.

One of the earliest cookbooks printed in America, The Frugal Housewife made no mention of colonial cooking or American ingredients, and it presumed access to cooking tools and technologies that were all but impossible to acquire in the colonies. Despite these obvious shortcomings in the colonial market, The Frugal Housewife sold quite well. The book remained in print in 1803. That year, an appendix was added that contained American recipes like Indian pudding, buckwheat cakes, and pumpkin pie.

Carter certainly did not write these; it appears that they were borrowed from a Swedish cookbook called Rural Oeconomy. (The exact same appendix showed up in the 1805 edition of Glasse’s The Art of Cookery! It’s likely that publishers decided this supplement would make both cookbooks more appealing to American audiences.) In 1832, Lydia Marie Child republished the cookbook as The American Frugal Housewife, and it would be reprinted multiple times over the next two decades.

Thanks to Carter, a number of traditional English dishes made their way into American foodways. But she didn’t do it on her own; she remains in debt to Amelia Simmons, who wrote the first truly American cookbook, American Cookery, in 1796. Simmons was heavily influenced by Carter and borrowed entire passages verbatim from The Frugal Housewife.

The interplay of culinary texts from Glasse, Carter, and Simmons superbly illustrates the rich history–and interaction–of global foodways. Each of these women’s cookbooks significantly impacted colonial cookery.

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.