One hundred years after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published, Langston Hughes called the novel “the most cussed and discussed book of its time.” Hughes’ failure to comment on the literary merits of Uncle Tom’s Cabin hints at the persistent disagreement among writers, critics, and the reading public about the novel’s actual quality. Stowe’s contemporaries who found the book overly sentimental, extreme, or otherwise objectionable could not avoid discussing the book–on either side of the Atlantic. That included Charles Dickens, who initially endorsed Uncle Tom’s Cabin but came to resent the less than complimentary comparisons made between his own views and works and Stowe’s.

A Fortuitously Timed Publication

It seemed that Stowe had chosen precisely the right moment to publish an anti-slavery novel. The Fugitive Slave Act had passed in 1850, and the divisive legislation directly affected the Stowe household. Stowe had thought that one of her servants was a freed slave, but the girl had actually run away from a Kentucky plantation. When Stowe learned that the girl’s former owner was looking for her, Stowe immediately set out to find a safe hiding place for the girl. The episode would be one of many that inspired Stowe to undertake an abolitionist novel (though she would later claim that God himself was guiding her pen).

Such events happened all over the country, and the nation was ripe for just such a work as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. On May 8, 1851, the first installment of appeared in Washington DC’s National Era, which was owned by abolitionist Gamaliel Bailey. The piece was immediately popular; sales and readership of the National Era jumped from 17,000 to 28,000 while the story ran. Before the last installment had even appeared, Stowe already had an offer from John J Jewett & Co. to publish Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a single volume.

Such events happened all over the country, and the nation was ripe for just such a work as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. On May 8, 1851, the first installment of appeared in Washington DC’s National Era, which was owned by abolitionist Gamaliel Bailey. The piece was immediately popular; sales and readership of the National Era jumped from 17,000 to 28,000 while the story ran. Before the last installment had even appeared, Stowe already had an offer from John J Jewett & Co. to publish Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a single volume.

That edition was published on March 20, 1852. Over 100,000 copies had sold by the end of the summer, and over 300,000 copies had sold by March 1853. Dramatic versions of the novel appeared within months, and George L Aiken’s stage production remained among the most popular plays in England and America for the next 75 years.

Not everyone was quite so enthusiastic. Southerner William Gilmore Simms considered the novel both libelous and poorly researched. Reverend Joel Parker threatened to sue Stowe for her “dastardly attack” on his character. And Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been banned in the South at numerous points in history. The negative publicity induced Stowe to write The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853) to defend herself. Either way, all the attention only served to increase Stowe’s fame.

An American Novel Goes Abroad

To expand her readership, Stowe sent presentation copies to a number of illustrious personages, from Prince Albert to the Reverend Charles Kingsley. Among the recipients was Charles Dickens, who received a little lavender-bound volume with a letter from Stowe. The American novelist evoked their shared mission, stating that “The Author of the following sketches offers them to your notice as the first writer in our day who turned the attention of the high to the joys and sorrows of the lowly.”

Dickens responded with guarded praise, complimenting Stowe’s noble cause. He was less restrained in expressing his opinion of the book later that year. Dickens reportedly told Sara Jane Clarke, a young American visiting Tavistock House, “Mrs. Stowe hardly gives the Anglo-Saxon fair play. I liked what I saw of the colored people in the States. I found them singularly polite and amiable, and in some instances decidedly clever; but then I have no prejudice against white people.” Clarke wrote, “Uncle Tom evidently struck him as an impossible piece of ebony perfection…and other African characters in the book as too highly seasoned with the virtues.” She noted that Dickens argued Uncle Tom’s Cabin was “scarcely a work of art.”

Stowe Proves Impossible to Ignore

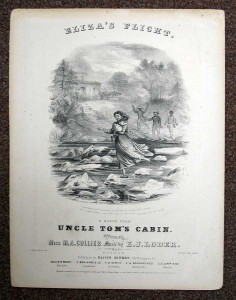

This piece of music published the same year as the novel – most likely due to the intense popularity Stowe’s work enjoyed right from the beginning. OCLC records nine institutional holdings.

By mid-1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was selling quickly in both America and England. Dickens simply couldn’t avoid talking and writing about the novel because it was simply what everyone wanted to discuss and read about. Thus he and Henry Morley wrote an article for the September 18, 1852 issue of Household Words called “North American Slavery.” The article opened with a critique of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Dickens called the novel a “noble work,” before pointing out its “overstraining conclusions and violent extremes.” But then Dickens turned his pen to the author: “Harriet Beecher Stowe is an honor to the time that has produced her, and will take her place among the best writers of fiction.”

Before the article ran, however, Dickens was dragged into a most unpleasant controversy. On September 13, 1852, Lord Denmon, the former Lord Chief Justice of England and a friend of Dickens, launched a rather vicious attack against Dickens. He published an article in the London Standard critiquing both Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the first seven numbers of Bleak House. A staunch abolitionist, Denmon castigated Dickens for obstructing the abolitionist cause. He brought up the character of Mrs. Jellyby, “a disgusting picture of a woman who pretends zeal for the happiness of Africa…if it means to represent a class, we believe that no representation was ever more false.”

Denmon went on to publish five more columns in the Standard, which were subsequently republished for circulation in pamphlet form. In the third, Denmon satirized Dickens’ initial praise of Stowe, saying “Mrs. Stowe might have learned a more judicious mode of treating a subject from the pictures of Mrs. Dombey and Carker, of Lady Dedlock and Joe [sic]. Uncle Tom ought not to have come to his death by flogging. A railway collision, such as disposed conveniently of Mr. Carker, would have been much more artistic.” By the fifth piece, Denmon finally abandons Dickens to heap praises on Stowe’s “graphic skill and pathetic power in which she has so far surpassed all living writers.”

Dickens Tries to Quash the Controversy

Dickens didn’t publicly respond to Denmon right away. He probably would have preferred to avoid all discourse on Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin altogether, but that was impossible. Indeed, he gets drawn into talking about the novel in his correspondence on more than one occasion, most notably with the Duke of Devonshire (October 29, 1852) and three weeks later with Mrs. Watson.

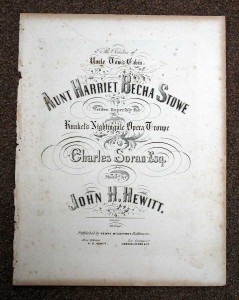

“Aunt Harriet Becha (sic) Stowe” was written for Kunkel’s Nightingale Opera Troupe. OCLC records five institutional holdings.

Mrs. Cropper, Denmon’s daughter, wrote Dickens a letter of apology toward the end of 1852. She said that her father had suffered a severe paralytic stroke on December 2, 1852 and was not himself. Indeed, he had been forced to resign his post as Lord Chief Justice because of similar strokes. Dickens’ response indicates his growing resentment toward Stowe, who was now receiving praise at Dickens’ expense from a host of critics. Dickens argued that the best means to further the cause of abolition was not exaggerated emotional appeals and painting slave owners in the worst possible light, but rather reason and rational argument.

Dickens also felt that Stowe’s novel was being used as an “angry weapon” against him. He observed that the “exactly four words of objection to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (amidst the most ardent praise of it)” had resulted in unjust attacks on him. Cropper had her brother George draft a response to Dickens, but Dickens replied on January 21, 1853 with an aim of ending the matter completely. He sent back Cropper’s letter unopened.

An Unexpected Encounter

Unfortunately for Dickens, he couldn’t end his exposure to Stowe quite so easily. Now famous on both continents, Stowe embarked on a tour of the United Kingdom, and Dickens was to meet her. Her travel schedule proved unpredictable, so Dickens had virtually no time to prepare. Stowe and her husband arrived in London on May 2, 1853, which happened to be the day that the Lord Mayor was hosting a large banquet. Eager to show Stowe the proper hospitality, the Mayor immediately extended an invitation. He seated the Stowes directly across from Dickens and his wife, Catherine.

Unaware that Dickens harbored a grudge, Stowe was thrilled to be in Dickens’ company. She was impressed with him and his wife, noting later that they were “people that one couldn’t know a little of without desiring to know more.” Once the crowd had had several rounds of alcohol, Thomas Noon Talfourd proposed a toast to the literature of England and America. He noted how both Dickens and Stowe “employed fiction as a means of awakening the attention of their respective countries to the condition of the oppressed and suffering classes.” Then Talfourd made a toast to Dickens. Dickens stood and offered kind words to Stowe. Thus the evening appeared to go pleasantly enough. A few days later, Dickens took Catherine to call on Stowe and her husband at Walworth. Stowe returned the visit, only to find that Dickens was ill and Catherine was busy ministering to him.

In 1854, Stowe published Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands, recounting her visit to England. She specifically mentioned her meeting with Catherine Dickens, calling her a “good specimen of a truly English woman: tall, large, and well-developed, with fine, healthy color, and an air of frankness, cheerfulness, and reliability.” Perhaps Stowe was already predisposed to like Catherine. After all, she had championed an anti-slavery appeal, helping to collect about 500,000 signatures. The document, titled “An Affectionate and Christian Address from Many Thousands of Women of Great Britain and Ireland to Their Sisters, the Women of the United States of America.” The document was bound in 26 huge volumes and sent to Stowe.

By this time, however, Dickens had a very different view of his wife’s character. Thus Stowe’s lavish praise rankled him. He was sure to mention to others that Stowe had called Catherine “large.” Dickens also found Sunny Memories quite trite and dubbed the book “Moony Memories.” He wrote to a friend, “the Moony Memories are very silly I am afraid. Some of the people remembered most moonily are terrible humbugs–mortal, deadly incarnations of Cant and Quackery.”

Stowe Returns for a British Copyright

Stowe made a second visit to England in 1856, but she would not again encounter Dickens. This time, she met Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, along with Lord Byron and his wife Anne Isabella Milbanke, Lady Byron. The visit came on the heels of Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, another anti-slavery novel that was successful but not wildly popular like Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

During this second trip to England, Stowe and Dickens may have found common ground: Stowe’s primary purpose was to get a British copyright on her new book. She hadn’t held one for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, losing untold profit on all the copies sold abroad. Dickens, a long-time proponent of international copyright law, might have empathized with Stowe, given that he’d lost major sums thanks to pirated editions of his books in America.

A New Offense

For the next several years, there’s no evidence that Dickens discussed Stowe or Uncle Tom’s Cabin either in print or in correspondence. That changed in September 1869. That year, James T Fields, Dickens’ friend and American publisher, decided to run Stowe’s The True Story of Lady Byron’s Life in Atlantic Monthly. The piece delved into the Byrons’ private lives, unabashedly addressing the incestuous relationship between Lord Byron and his half-sister Augusta Leigh. Stowe intended to vindicate Lady Byron by exposing her husband’s depravity.

Dickens found such a work unconscionable. He’d always been vehemently opposed to prying into the lives of private figures; Dickens even called James Boswell an “unconscious coxcomb” for having written his biography of Samuel Johnson. Dickens was even sensitive once his own marriage fell apart and he started an affair with Ellen Ternan. Indeed, a simple indiscreet comment from William Makepeace Thackeray was among the first in a series of events that destroyed Thackeray and Dickens’ friendship. To protect his own privacy, Dickens even went to far as to make a bonfire at Gads Hill in September 1860, with the sole purpose of burning his own papers and correspondence.

Thus it should come as no surprise that on October 6, 1869 Dickens wrote to Fields, “Wish you had nothing to do with that Byron matter. Wish Mrs. Stowe was in the pillory.” And on October 18, 1869, he wrote to the actor Macready, “May you be as disgusted with Mrs. Stowe as I am.” He argued, “It seems to me that to knock Mrs. Beecher Stowe on the head, and confiscate everything about [the Byron affair] in a great international bonfire to be simultaneously lighted over the whole civilized earth, would be the only pleasant way of putting an end to the business.”

Yet Stowe’s brief foray into celebrity scandal would hardly remain a memorable part of her career. As she got older, she increasingly turned to more domestic subjects. None of her subsequent works would come close to reaching the popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Regardless of the book’s literary merits (or lack thereof), Uncle Tom’s Cabin has proven an incredibly powerful piece of literature. That’s evident in President Abraham Lincoln’s apocryphal greeting to Stowe, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started the Great War!” Whether that’s true or not, the fact that it could be true aptly demonstrates the incredible impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Related Posts:

Charles Dickens the Copyright Confederate

How the “Dickens Controversy” Changed American Publishing

The California Gold Rush, Slavery, and the Civil War

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.