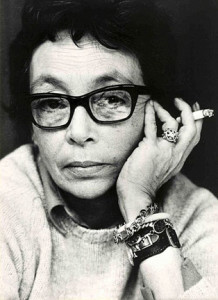

By Margueritte Peterson

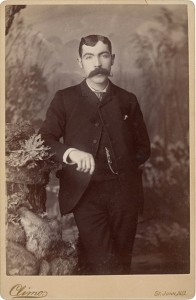

September 24th is the anniversary of the birth of one of the most well-known Western writers of the 20th century. Notice I did not say one of the most prolific writers in history, as this novelist only published 4 titles throughout his (unfortunately brief) lifetime. However, it must be said that though these titles garnered only modest success throughout his short life, F. Scott Fitzgerald has since become internationally famous and is known as one of the most important voices of the Jazz Age… not to mention a front-runner of Modern American Literature.

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1896, Fitzgerald was loosely related (second cousin three times removed kind of loose… the kind that you can marry in any state, really) to Francis Scott Key – the composer of the national anthem – and was named in his honor. A few months before he was born, his two older sisters died before their 5th birthdays. Fitzgerald cited their death, while he was still in the womb, to be the moment when he became a writer. After spending a few years of his childhood living in Buffalo, New York with his doting parents, the family moved back to Minnesota. At the age of 13 Fitzgerald saw his first work published – a detective mystery in his school newspaper. He continued to write throughout his few years at Princeton University, where, as young men are wont, he eventually came to be on academic probation and consequently dropped out of school to join the army. Around this time, Charles Scribner’s Sons rejected two of his early works, one of which is The Romantic Egotist.

As a young lieutenant stationed in Alabama, Fitzgerald met and fell in love with the daughter of the Alabama Supreme Court Justice. Though Zelda initially accepted a marriage proposal from Fitzgerald, she eventually changed her mind under the impression that he would not make enough money to support the lifestyle she was used to. Once Fitzgerald was discharged from the army, he moved to New York, desperate to make enough money to impress Zelda and win her back. (I feel like nowadays that kind of spoiled behavior wouldn’t fly… unfortunately). Fitzgerald worked full-time for an advertising agency and even repaired automobiles on the side to save as much as he could. However, he was unable to convince the beautiful Alabama socialite, and returned home disheartened. In St. Paul, Fitzgerald took the time to revise his earlier novel The Romantic Egotist into what he renamed This Side of Paradise. This time around, Scribner’s accepted the novel and when it was published in March of 1920 the title sold over 41,000 copies in the first year alone. Fitzgerald became famous overnight – and with the steady income from the book and the demands for more literature, he suddenly was in a position Zelda could accept – the two were married only a week after and by October of 1921 their daughter “Scottie” was born.

In the 1920s the Fitzgeralds spent a significant amount of time in Paris – enjoying themselves with the other American expatriates living there (most notably Ernest Hemingway). Though Hemingway did not approve of Fitzgerald’s marriage to Zelda (supposedly calling her “insane” and believing that she stifled Fitzgerald’s talent out of jealousy), the friendship between Hemingway and Fitzgerald was one of the most important in FItzgerald’s short life. Though they eventually drifted apart, Fitzgerald held Hemingway’s work in the highest regard and strove to achieve the same success his friend experienced.

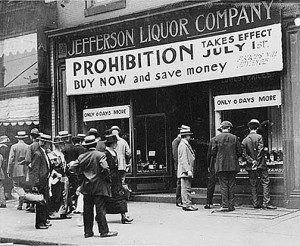

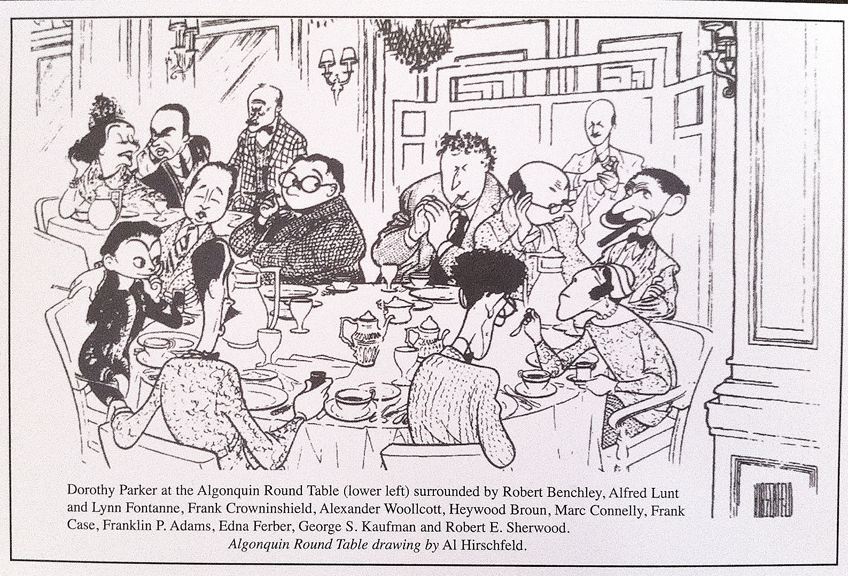

Despite the author’s fame and talent, the Fitzgeralds were in a constant state of financial worry. Throughout his life, F. Scott borrowed money from friends and took out loans – as only his first novel made enough money to support their lifestyle. Though his passion lay in writing novels, Fitzgerald made most of his money by publishing short stories in journals and periodicals – a few notable stories being “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz”, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”, “The Last of the Belles” and “The Camel’s Back.” They were well-known as great partiers and drinkers, and as the “belles” of the Jazz Age, they lived up to their reputations. Around 1930 Zelda began to suffer from schizophrenia, an illness that took a great toll on their relationship as well as Scott’s writing. For the rest of her life, Zelda would be treated in Psychiatric Hospitals and wards in both America and Europe (the pair moved back to Maryland in the 30s to give themselves a more stable lifestyle – one that would hopefully allow Fitzgerald a better chance at writing more steadily. These years were far from easy for the pair, and in 1937 Scott moved to Los Angeles to work on (what he considered degrading) film scripts and commercial short stories. He and Zelda’s fiery relationship became too hard to bear and for the rest of his short life he and his wife would be estranged, with her living in and out of mental hospitals on the east coast.

In his years in Hollywood Fitzgerald suffered two heart attacks, the second being the cause of his death at the young age of 44. He was, at that time, working on his fifth novel, The Love of the Last Tycoon, which remained unfinished at his death. A literary critic and personal friend of Fitzgerald, Edmund Wilson, published the work in 1941 after Scott’s death as The Last Tycoon, but an unedited version surfaced in 1994 and was published under the original title. Fitzgerald, though now recognized as one of the most influential authors of the Jazz Age, was not necessarily recognized in his lifetime as such. As stated, only his first novel was as commercially successful as one would expect, given his fame in recent day. (EvenThe Great Gatsby was not the front-runner Jazz Age title we know it as today.) Now, on his 119th birthday, he is one of the most famous American authors ever known. Why is that, you may ask? Well, you’ll have to check back next September 24th on his 120th birthday, when we examine why humanity likes to change its mind!

Just kidding. I have no idea what will be being written next September 24th. Doesn’t mean you shouldn’t check back though!