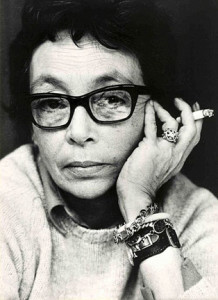

Throughout history, writers have been known to cause a stir. The Marquis de Sade was incarcerated in an insane asylum for his erotic tales. Oscar Wilde self-exiled himself to Paris for the unimaginable treatment he received for the “crime” of homosexuality. Harriet Beecher Stowe caused a flurry of activity around the anti-slavery act in the United States. Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita was banned in many different countries, including France (you know it’s controversial when even the French consider it obscene…). In modern day we have parents and schools banning books by authors like Judy Blume and Laurie Halse Anderson because they deal with sex and coming-of-age experiences in young adult fiction. We can only imagine the hell-fire that would begin to burn should any school library choose to keep a holding of The Lover or The Ravishing of Lol Stein on hand! Marguerite Duras, a French novelist, essayist, playwright and film director, could certainly be considered controversial in both work (like the Marquis) and life (like Wilde). Despite the often explicit and controversial themes and plots in her novels, many of which were drawn from her real-life experiences, Duras has been a beloved figure in the field of “serious literature” (a genre I just made up, you’ll be pleased to know) for decades.

Marguerite as a young girl in Indochina, pictured here with her brothers Pierre and Paulo and a friend.

Marguerite Donnadieu (pen name Duras, taken after the French town where her father passed away) was born in Saigon (at that time in an area called Gia-Dinh), French Indochina in April of 1914. Duras’ father died when she was only 4, and Duras and her two brothers were raised in relative poverty by her mother. Duras made frequent allusions to having always wanted to be a writer, though had fewer literary influences on her writing in early life than other children her age. It is very likely that this lack of a compass for creative writing helped shape her singular style later. Duras’ childhood was anything but average, as growing up French but poor in Indochina was far from ideal. According to Duras, her older brother Pierre had a mean streak and bullied his two younger siblings mercilessly. Her younger brother Paulo seemed a touch mentally challenged and was, supposedly, the only thing she cared for as a child and teenager. As a teenager, Duras began an affair with an older Chinese merchant, Huynh Thuy Le, a time in her life that would often be revisted in her later work. Two of the works she is most famous for, in fact, are her novels The Lover and The North China Lover, throughout both of which she uses her minimal style to describe her teen years and her sexual awakening with Huynh Thuy Le.

When Duras was 17 she left Saigon for Paris, where she began studying for a degree in mathematics (before changing her mind and trying political science and law, as well). She was an active supporter of the French Communist Party (the PCF), and in her mid to late twenties she worked representing the colony of Indochina for the French government. A member of the French Resistance during World War II, Duras experienced even further pain and hardship when her brother Paulo died in 1942, and then when her new husband Robert Antelme was deported to Buchenwald concentration camp for his involvement with the Resistance, and scarcely survived the experience.

By the 1950s, Duras had established herself as a writer and has continued to be published ever since. In the 1960s, she began to write plays and film scripts, but also continued writing essays and novels. As Leslie Garis of the New York Times writes, “The form of a typical Duras novel is minimal, with no character description, and much dialogue, often unattributed and without quotation marks. The novel is not driven by narrative, but by a detached psychological probing, which, with its complexity and contradictory emotions, has its own urgency… a chronic underlying panic…” Though often Duras’ work is considered part of the Nouveau Roman literary movement begun in the 1950s, the truth is that, though appreciating and using the conceptual flowing of time as modern literature often did, she was not preoccupied by some of the more grammatical and literary principles as other writers of the movement were. Once again, perhaps this disinterest in contemporary writing styles, fads or “correctness” can be attributed to her meager literary influences as a young girl.

Some of Duras’ other well-known works include Moderato Cantabile (1958), Hiroshima Mon Amour (1960), The Ravishing of Lol Stein (1964), India Song (1976), The Malady of Death (1982), The Lover (1984), and No More (1995 – published just a year before the author’s death). Many of her works deal with sexuality, but a central theme in her works is transition – whether it be the growth of her characters from children to adult, from place to place or even from “normal” to “artist” (one could argue that her novel The Lover encompasses all of these themes). Her film scripts are well-known, the most famous of which is her film adaptation of her own novel Hiroshima Mon Amour, with striking dialogue that not all authors of novels could have produced. Duras felt that words were in constant fluctuation, that words themselves had more power than the author wielding them did, as books and stories of the same writer could be read differently by many. In her novel Summer Rain (1992), Duras writes, “Words don’t change their shape, they change their meaning, their function… They don’t have a meaning of their own any more, they refer to other words that you don’t know, that you’ve never read of heard… you’ve never seen their shape, but you feel… you suspect… they correspond to an empty space inside you… or in the universe.”

Duras struggled with alcoholism her whole life. In October of 1988 at the age of 74, Duras fell into a coma that she miraculously woke up from 5 months later. The author continued to write, and to fight, until she died in 1996 of throat cancer. Her legacy as one of the great writers of the 20th century is not soon to be forgotten, and her stories (of love, lust, awakening, transition, madness and pain) speak to readers across the world.