“Broadsides are the most legitimate representatives of the most ephemeral literature, the least likely to escape destruction, and yet they are the most vivid exhibitors of the manners, arts, and daily life, of communities and nations. They imply a vast deal more than they literally express, and disclose visions of interior conditions of society, such as cannot be found in formal narratives.”

-Samuel F Haven

Samuel F Haven, former librarian for the American Antiquarian Society, presided over one of the largest collections of broadsides in the world. Historians and rare book collectors alike cherish broadsides because they offer snapshots of moments in time, helping us to understand the zeitgeist of that era. Broadsides make ideal complements to a rare book collection, granting the collection greater depth and context.

What a Broadside Is (and Isn’t)

Broadsides are single-sheet documents that are printed on only one side. They’re sometimes also called broadsheets. They’re different from handbills, which are smaller and printed on both sides. Broadsides should also not be confused with leaflets or booklets, which are folded from a single sheet of paper. The size of broadsides varies greatly, but they are generally smaller than posters and billboards.

Early broadsides didn’t include illustrations. They were simple documents printed in black ink. As printing processes got more sophisticated over time, the broadside also evolved. They began to include stock illustrations done from copper or wood engravings and eventually bore more intricate and relevant illustrations.

The Emergence and Decline of Broadsides

In Europe, broadsides came into use almost as soon as the printing press was invented. They first appeared in the United States during the seventeenth century, which the technology of moveable type and the printing press finally made its way to the colonies. For centuries, the broadside was the preferred format for delivering public announcements. They were also a cost effective way to distribute poetry, songs, and satire.

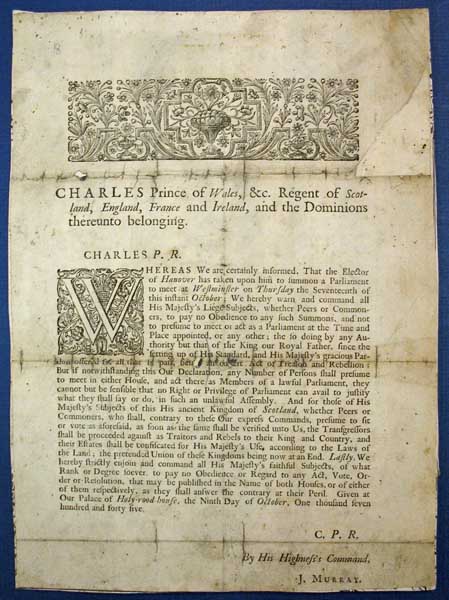

Bonnie Prince Charlie declares the illegitimacy of Parliament and calls all its attendees traitors. A fantastic artifact from the Jacobite rebellion.

Perhaps the most famous broadside in the United States is the broadside version of the Declaration of Independence published by John Durham on July 4 and 5, 1776. Thanks to this document, news of the declaration swept through the colonies. The John Durham broadside is a perfect example of how these artifacts can encapsulate a pivotal moment in history. Only a few decades earlier, Prince Charles of Wales had used a broadside to make a truly shocking announcement. He declared Parliament illegitimate and branded its participants as traitors. The broadside captures the heat of the Jacobite rebellion.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, broadsides had begun to fall into disuse. They’d been replaced by newspapers and radio for delivering news. Posters and billboards had replaced broadsides as advertisements. Today the occasional fine press artist produces a broadside, but the form has been rendered obsolete by technology.

Preserving and Collecting Broadsides

Broadsides fall into the category of ephemera because they weren’t made to last long. They were intended for quick consumption and therefore were often printed on cheap paper. Few people thought to keep broadsides, and the ones that did get saved are often in less than ideal condition. They may have folds and rips, or they may have been poorly repaired using the wrong materials. To protect broadsides from further damage, it’s important to protect them with a mylar sheath. Your broadsides can then be stored flat in a climate controlled environment.

The broadside edition of Macdonald’s “A Song for Chistmas” is incredibly rare. This is an inscribed presentation copy.

Meanwhile the ephemeral nature of broadsides is what makes them so valuable to rare book collectors. Some people actually specialize in broadsides. But the avid collector may supplement works by a favorite author with related broadsides. For example, a collector of George Macdonald would be interested in the broadside edition of Macdonald’s poem “A Song for Christmas.” Published around 1887, the broadside is the first appearance of the poem. It’s not published again until the 1890’s, when it appears in a collected volume. Macdonald’s “A Song for Christmas” broadside is now extremely rare; OCLC and KVK document only one other copy, at the Library of Scotland.

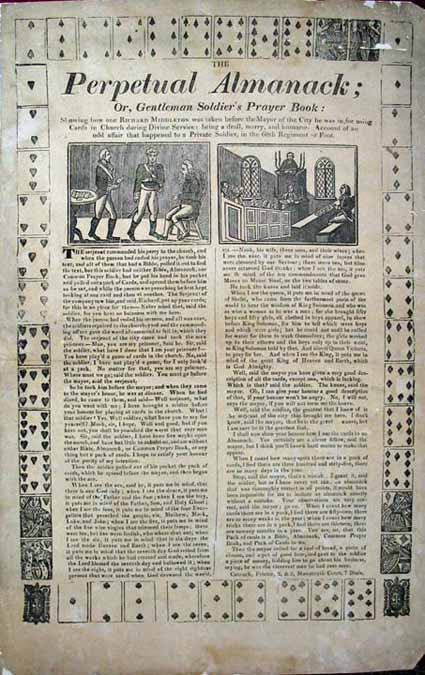

Chatto referred to this very broadside in his “Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards”

Sometimes broadsides even served as sources for authors. William Andrew Chatto wrote about leisurely pursuits such as fly-fishing, smoking, and playing cards. In his 1848 Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards, Chatto cites a Catnatch broadside called “The Perpetual Almanack; or, Gentleman Soldier’s Prayer Book.” The broadside tells the tale of Richard Middleton, who was taken before the mayor for using cards during a church service. Chatto notes that his own cards have been a “moral monitor and help to devotion.”

As your rare book collection progresses, incorporating broadsides is an excellent step to broaden the scope of the collection. What was the first broadside in your collection? And why did it appeal to you?