By Margueritte Peterson

“[Menken] is a sensitive poet who, unfortunately, cannot write.” -Charles Dickens

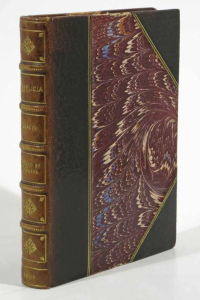

Adah Isaacs Menken died in Paris on August 10, 1868, only eight days before her collection of poems, Infelicia would be published. Dedicated to Charles Dickens, Infelicia highlights Menken’s complicated relationship with her literary contemporaries—and, perhaps, her unfailing talent for generating publicity. Details about Menken’s early life are difficult to corroborate because Menken herself told so many different versions of her story. Most experts agree that she was born on June 15, 1835 in Memphis, and that her given name was Adah Bertha Theodore. She moved to Lousiana as a young child, grew up there, and launched her acting career there. From Louisiana, Menken traveled throughout the South and West. Meanwhile, she launched her writing career with “Fugitive Pencillings,” which appeared in Texas’ Liberty Gazette and the Cincinatti Israelite.

Adah Isaacs Menken died in Paris on August 10, 1868, only eight days before her collection of poems, Infelicia would be published. Dedicated to Charles Dickens, Infelicia highlights Menken’s complicated relationship with her literary contemporaries—and, perhaps, her unfailing talent for generating publicity. Details about Menken’s early life are difficult to corroborate because Menken herself told so many different versions of her story. Most experts agree that she was born on June 15, 1835 in Memphis, and that her given name was Adah Bertha Theodore. She moved to Lousiana as a young child, grew up there, and launched her acting career there. From Louisiana, Menken traveled throughout the South and West. Meanwhile, she launched her writing career with “Fugitive Pencillings,” which appeared in Texas’ Liberty Gazette and the Cincinatti Israelite.

The year 1856 brought the first of Menken’s multiple marriages, to Alexander Isaacs Menken. The two were (supposedly) divorced already when Menken entered her next marriage with prizefighter John Heenan in 1859. But Heenan and Menken separated shortly thereafter; Heenan was scandalized to find that his new wife was still legally married to her first husband. By this time, Menken had already begun traveling in bohemian and literary circles. A regular at Pfaff’s, Menken met Walt Whitman, who greatly influenced her work.

Soon Menken was “not known for her talent, but rather for her frenetic energy, her charismatic presence, and her willingness to expose herself.” Indeed, Menken’s primary claim to fame was her performance in Mazeppa. Menken played the role of a man, and in one scene she was lashed to the back of a running horse…wearing nothing but a flesh-colored body stocking.

The play debuted in Albany in June, 1861. Menken’s manager, Edwin James was a sports reporter for the New York Clipper (and a former lawyer who’d inspired the character of Striver in Tale of Two Cities.) James managed to get reporters from all six of New York’s daily papers to attend, along with reporters from three weeklies and two monthlies. Although the Civil War had already broken out, Menken’s performance grabbed headlines. Mark Twain saw Mazeppa at Tom Maguire’s Opera House in San Francisco. Though he had formerly dismissed Menken as a “shape actress,” her performance changed his mind. On September 13, 1863, he wrote a column called “The Menken—Written Especially for Gentlemen.” His assessment of Menken was less than sterling:

“Here every tongue sings the praises of her matchless grace, her supple gestures, her charming attitudes. Well, possibly, these tongues are right. In the first act, she rushes on the stage, and goes cavorting around after ‘Olinska’; she bends herself back like a bow; she pitches headforemost at the atmosphere like a battering ram; she works her arms, and her legs, and her whole body like a dancing-jack: her every movement is as quick as thought; in a word, without any apparent reason for it, she carries on like a lunatic from the beginning of the act to the end of it. At other times she ‘whallops’ herself down on the stage, and rolls over as does the sportive pack-mule after his burden is removed. If this be grace then the Menken is eminently graceful.”

At any rate, Menken continued to bring crowds to theatre after theatre. Always the shrewd self-promotor, she would arrive in a new city and immediately ensure that her photograph was hanging in every shop window. By now Menken had also gotten into the habit of inventing stories about herself. She also frequently exaggerated the extent of her relationship with famous figures, particularly those in the literary world.

Mazeppa opened in London on October 3, 1864. Charles Dickens attempted to attend an early performance, only to find that the show was already sold out. The ticket manager recognized Dickens and offered him a private box, but Dickens declined. It’s long been rumored that Menken used the incident as an excuse to meet Dickens, but it’s likely that Menken started that rumor herself. The two traveled in the same social circles, and Dickens may even have attended some of Menken’s “literary salons” at her rooms in the Westminster Hotel. But there’s little evidence to suggest a deeper relationship, and even the rumor of an association with Dickens would have bolstered Menken’s reputation.

Meanwhile, Menken’s connection to Dickens’ contemporary Algernon Charles Swinburne was anything but a rumor. Fearing that Swinburne had lost his interest in the opposite sex, his associates set him up with the sexy Menken. After Menken’s death, Swinburne would say of her, “She was most loveable as a friend, as was as as a mistress.”

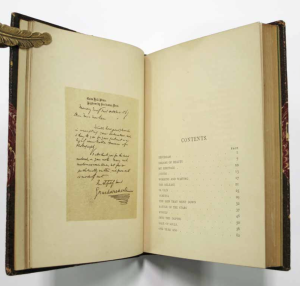

A shot of the inserted facsimile letter in our holding of Felicia.

By 1868, Menken had published more than enough poems to publish a collection, which she titled Infelicia. Menken made another probably-calculated move: she dedicated the book to Charles Dickens, who by now enjoyed the Victorian equivalent of rockstar status in both England and America. The first edition included an engraved portrait of Menken on the frontispiece, along with a poem that Swinburne had written for her. It also included a facsimile of a letter that Dickens had supposedly written to Menken, thanking her for the dedication.

While Dickens did indeed thank Menken for the dedication, the facsimile was actually comprised of two different letters Dickens had sent to Menken. Thus this first edition was quickly suppressed, and subsequent editions don’t include the facsimile. This only added to the sensation that already surrounded the book. The dedication to Dickens left many speculating about the true nature of their relationship, and Menken’s untimely death had catapulted her back into the headlines.

Meanwhile, her relationship with Swinburne and the fact that the frontispiece bore a Swinburne poem led some to suggest that Swinburne or his assistant, John Thomson, had actually authored Infelicia. Critics soon pointed out, however, that the poems were riddled with flaws and simply weren’t that good. They eventually accepted the work as Menken’s, arguing that Swinburne was too talented to write it.

Infelicia went through a number of editions in England and America, mostly pirated. The book made its last appearance in 1902. It’s now quite rare to find a copy of Infelicia that bears that facsimile letter from Charles Dickens.