By Margueritte Peterson

So begins my favorite poem. I was never much of a poetry buff – having to read out badly handwritten poems in the 5th grade and then being the last one in the class to be chosen to be published in a strange Florida Kids Poetry Book pretty much nipped any dreams I might have had of being the next Emily Dickinson in the bud. In any event, I didn’t learn to appreciate poetry for a long, long time. Often I had trouble deciphering the meanings of the poems. In high school, a teacher would mark you wrong if you thought the poem had a different meaning than what she had thought. I always thought to myself, “how can that be right?” My English teacher wasn’t a close personal friend of Emily’s. Who is to say that what an academic somewhere decided was the meaning of Emily Dickinson’s poems is 100% what she meant. Isn’t a little part of poetry and literature in general interesting in that everyone reads it a bit differently?

But I digress.

Often, poetry can be a bit difficult for the average reader. (Especially if they are being graded on their feelings… okay, okay… I really will drop it now.) The poetry I have always preferred, given my lack of poetry deciphering skills, were the straight forward ones. The ones whose meanings were clear, which spoke to you in a way where you felt like the author was sharing a secret with you and only you. Poets like… Miss Elizabeth Bishop.

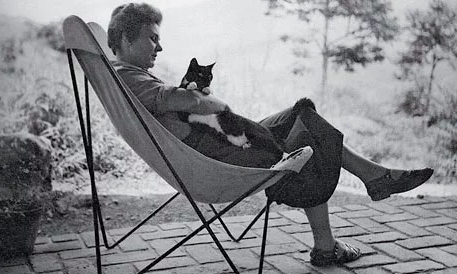

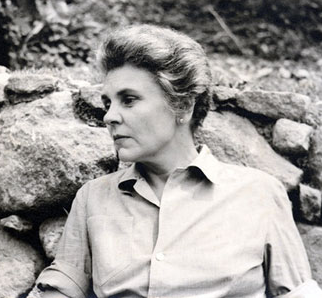

Elizabeth Bishop was born on February 8th (Happy Birthday!) in 1911, in Worcester, Massachusetts. She would have a sad childhood, however, as her father died before her first birthday and her mother went mad and was institutionalized in 1916 when Bishop was only 5 years old. She would never be reunited with her mother, and went to live with her maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia. Despite being ill often and developing asthma, Bishop wrote of her time in Nova Scotia as one of the happiest in her childhood. Custody of Bishop was then gained by her wealthier paternal grandparents a bit later in her childhood, and she was moved back to Worcester. Unfortunately she was unhappy with her paternal grandparents, and they could tell. In 1918, her grandparents sent Bishop to live with her mom’s eldest sister, Maud and her husband, and paid them for her upkeep. This was an important time for Elizabeth, as it was her aunt Maud who introduced her to poetry, reading her the works of the Victorian poets, including Tennyson, Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Thomas Carlyle. Without her knowledge, the seed to become a poet had been planted.

Bishop’s high schooling was a tad erratic, as she attended three different high schools until settling at Walnut Hill School, where she studied music with the idea of becoming a composer. At Walnut Hill her first poems were published in a student magazine. However, Bishop was still convinced that her future lay in music, not literature. She entered Vassar College in the fall of 1929 with these hopes – though they soon gave way when the fear of actually performing became too great for the shy Bishop. Instead, she threw herself into academia – focusing on her English classes and co-founding (with author Mary McCarthy) the underground university literary magazine Con Spirito. When she graduated in 1934, Bishop focused on traveling the world. She spent time living in Paris and in Key West, and wrote of her travels in poems, essays, and short stories. In fact, much of her writing done in Key West would be included in her first published book of poems, North and South (1946) – a book which won the Houghton Mifflin Prize for Poetry. Despite her popularity, however, Bishop wouldn’t publish another book of poetry for another 9 years. She still had enough money from the inheritance from her father to flourish in these locales, writing more for pleasure than for necessary income.

Bishop’s high schooling was a tad erratic, as she attended three different high schools until settling at Walnut Hill School, where she studied music with the idea of becoming a composer. At Walnut Hill her first poems were published in a student magazine. However, Bishop was still convinced that her future lay in music, not literature. She entered Vassar College in the fall of 1929 with these hopes – though they soon gave way when the fear of actually performing became too great for the shy Bishop. Instead, she threw herself into academia – focusing on her English classes and co-founding (with author Mary McCarthy) the underground university literary magazine Con Spirito. When she graduated in 1934, Bishop focused on traveling the world. She spent time living in Paris and in Key West, and wrote of her travels in poems, essays, and short stories. In fact, much of her writing done in Key West would be included in her first published book of poems, North and South (1946) – a book which won the Houghton Mifflin Prize for Poetry. Despite her popularity, however, Bishop wouldn’t publish another book of poetry for another 9 years. She still had enough money from the inheritance from her father to flourish in these locales, writing more for pleasure than for necessary income.

Her writing became more and more popular throughout the years, and almost 15 years later she would be elected as the Consultant in Poetry for the Library of Congress. Once her year as a consultant ended, Bishop began her travels once again and set out for South America in 1951. She intended to stay for two weeks, but fell in love with the female (and terribly gifted) Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares, and lived with her in Brazil for 15 years. Obviously at this time same-sex relationships were kept under wraps, which worked out just fine for the shy Bishop. During her time in Brazil, Bishop published a follow-up to her poetry collection North and South, and released Poems: North and South – A Cold Spring in 1955, and one year later won the Pulitzer Prize for this second book of poetry. Bishop enjoyed (or possibly didn’t enjoy, given her introverted nature) notoriety in both Brazil and the US over the next decade spent in Brazil with her lover. Unfortunately, over the years their relationship became strained and was tainted by Bishop’s alcoholism and heated fights. Soares committed suicide in 1967, after which Bishop would spend most of her days in the United States, away from the country that inspired much of her writing for so long.

Her writing became more and more popular throughout the years, and almost 15 years later she would be elected as the Consultant in Poetry for the Library of Congress. Once her year as a consultant ended, Bishop began her travels once again and set out for South America in 1951. She intended to stay for two weeks, but fell in love with the female (and terribly gifted) Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares, and lived with her in Brazil for 15 years. Obviously at this time same-sex relationships were kept under wraps, which worked out just fine for the shy Bishop. During her time in Brazil, Bishop published a follow-up to her poetry collection North and South, and released Poems: North and South – A Cold Spring in 1955, and one year later won the Pulitzer Prize for this second book of poetry. Bishop enjoyed (or possibly didn’t enjoy, given her introverted nature) notoriety in both Brazil and the US over the next decade spent in Brazil with her lover. Unfortunately, over the years their relationship became strained and was tainted by Bishop’s alcoholism and heated fights. Soares committed suicide in 1967, after which Bishop would spend most of her days in the United States, away from the country that inspired much of her writing for so long.

Her third publication, Questions of Travel, was published in 1965, and was unquestionably influenced by her time spent in South America. After this, she published a book of The Complete Poems in 1969, and then her last book to appear in her lifetime, Geography III, in 1977. Geography III won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, a prize which no woman had ever won and no American has won since. Bishop remained unbelievably popular throughout her life, until her sudden death in 1979 from a cerebral aneurysm.

Her third publication, Questions of Travel, was published in 1965, and was unquestionably influenced by her time spent in South America. After this, she published a book of The Complete Poems in 1969, and then her last book to appear in her lifetime, Geography III, in 1977. Geography III won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, a prize which no woman had ever won and no American has won since. Bishop remained unbelievably popular throughout her life, until her sudden death in 1979 from a cerebral aneurysm.