NOTE: Please understand that this blog contains heavy subject matter and foul language. You’ve been warned.

Censorship. A hated word in the bibliophile community. The very definition of the word seems off. Too… all encompassing.

Censorship is defined as: “the suppression or prohibition of any parts of books, films, news, etc. that are considered obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security.” Well now, from my own experience I can tell you that anything you write, anything you film, and anything you publish – it can and most likely will be offensive to someone. Someone, somewhere, will read your sentences with disdain. It is inevitable. It is why we have free speech. It is why you shouldn’t believe everything you read on the internet (including blogs). Censorship has won so many times over the centuries. How lucky we are to live in a country and be a generation that incorporates free speech and acceptance into our daily lives. If censorship was still at large, we would not be able to search anything we please on Youtube. We would be reading only what a small group of people we don’t know would be allowing us to read. Our President would not be allowed to post his every thought on Twitter.

Okay wait, perhaps censorship does have a silver lining.

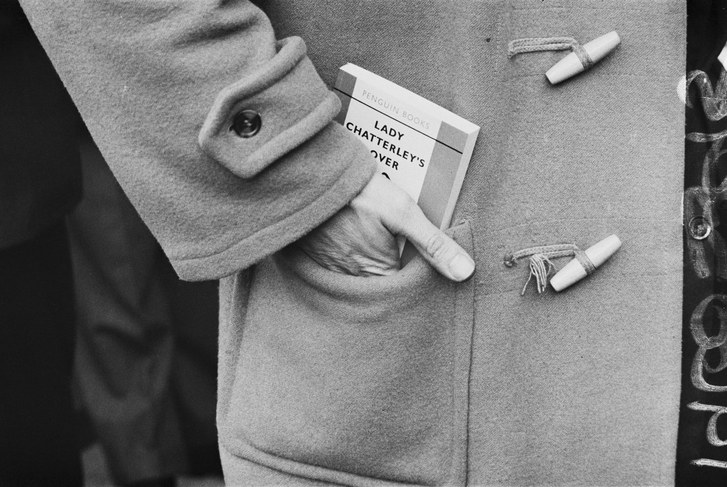

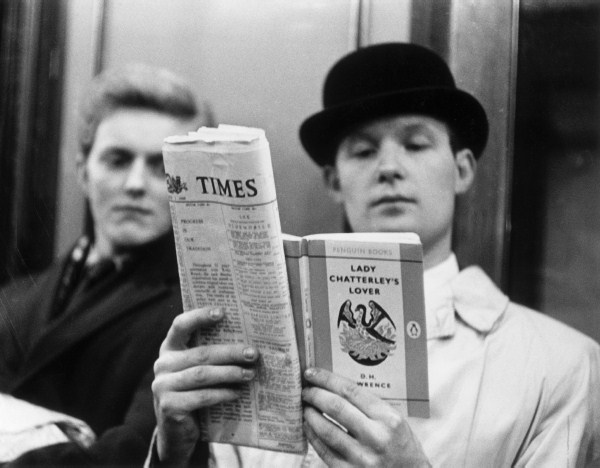

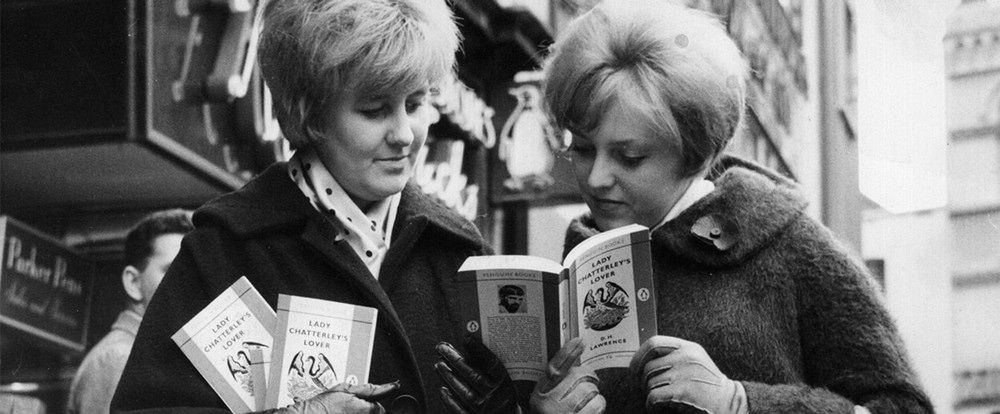

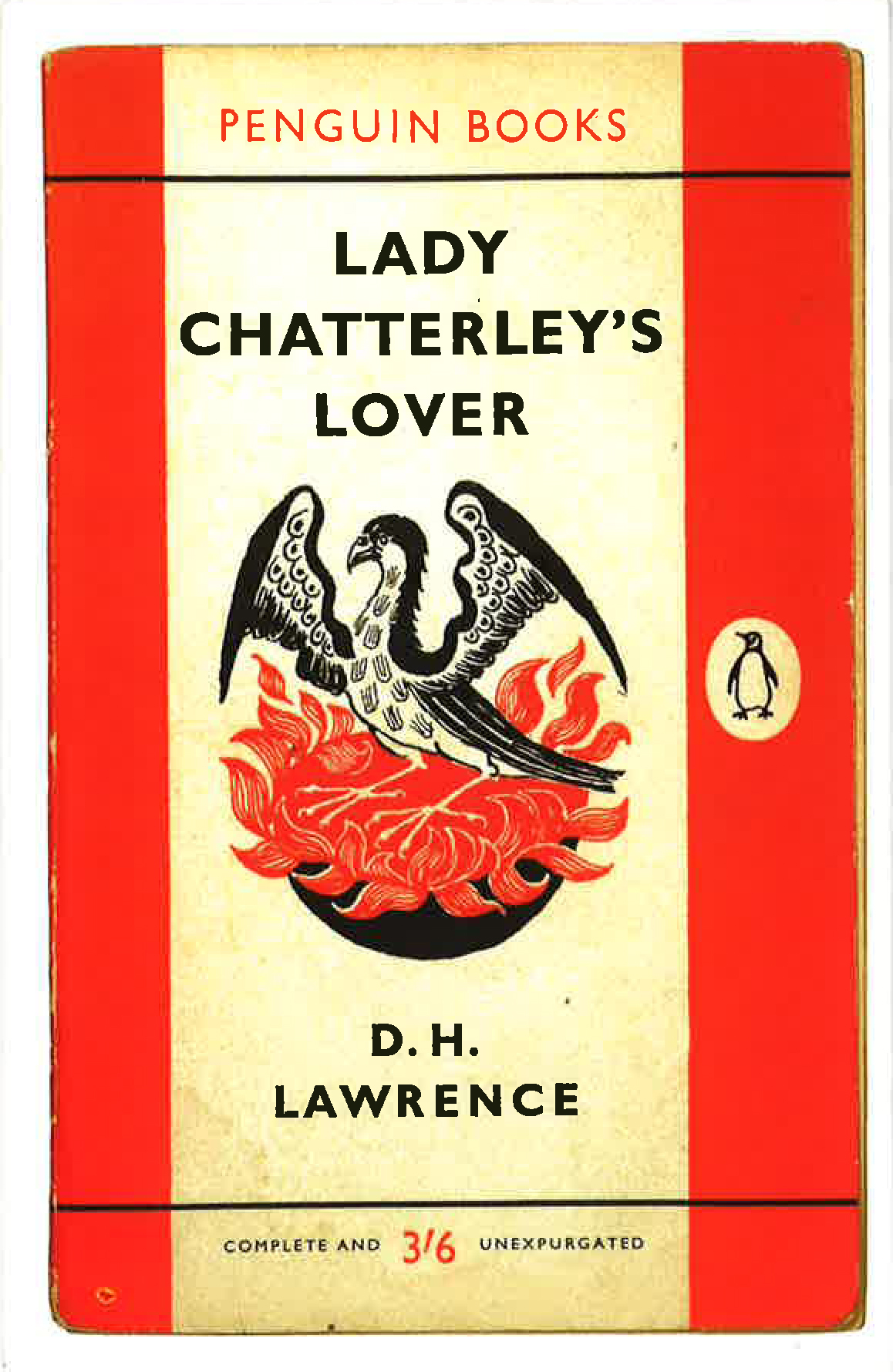

My point is – by and large – a world without censorship (as it has been known) is far superior to a world lived in the dark. On this day in 1960, censorship truly lost an epic battle in London. D. H. Lawrence, Penguin Books, Lady Chatterley and literature won, despite the fact that Lawrence was no longer around to enjoy his success. In one day, Penguin sold 200,000 copies of the title that had been banned since 1928. Over the next few months, over 3 million copies went home with their newly adoring owners. So what did the trial in 1960 truly do? As Geoffrey Robertson for the Guardian states, “No other jury verdict in British history has had such a deep social impact.” Let’s find out why.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover was privately printed for the first time in Florence in 1928. Due to illegal copying of the book, Lawrence arranged for a more legitimate publication of the book the following year in Paris. The British government immediately recognized its “disturbing” subject matter and the offensive language contained in the book – the opening prosecuting speech during the 1960 trial stated that “The word ‘fuck’ or ‘fucking’ appears no less than 30 times… ‘Cunt’ 14 times; ‘balls’ 13 times; ‘shit’ and ‘arse’ six times apiece; ‘cock’ four times; ‘piss’ three times, and so on.” Now, if you ask me… that’s just a list of dirty words. Perhaps the prosecution should have been censored, no? At least Lady Chatterley’s Lover had plot descriptions surrounding these words. In any case, Britain had spent the previous 30 years putting energy into keeping the book out of the country. So how did Penguin books win this battle in 1960?

The defense was aided in part due to the previous year’s 1959 Obscene Publications Act, which Parliament passed saying that in order for censorship to take place, the work in question would need to be considered as a whole – without singular focus on the dirtier bits. The prosecution did not fare well anyway, as, despite a conservative following not wishing to see the book in print and in the hands of anyone, lawyer Mervyn Griffith-Jones called no witnesses to support his argument (as no one agreed to stand for the prosecution) and merely suggested that the book had no literary merit. The defense, led by Gerald Gardiner (who would a mere four years later become Labour Lord Chancellor), had rather a different angle. He stated that the book did have merit, that Lawrence wasn’t simply writing smut, but attacking the “impersonality of the industrial age and loss of personal relationships… he was extolling the life-giving importance of romantic and sexual intimacy” (The Telegraph). Gardiner called 35 witnesses to his side – big wigs in academia and literary worlds. He even had a Bishop – the Bishop of Woolwich, who wrote that, though Lawrence was not a Christian himself, he was “portraying the act of sex as something valuable and sacred – as an act of communion” – he went so far as to say that Christians could easily read this title.

The defense was aided in part due to the previous year’s 1959 Obscene Publications Act, which Parliament passed saying that in order for censorship to take place, the work in question would need to be considered as a whole – without singular focus on the dirtier bits. The prosecution did not fare well anyway, as, despite a conservative following not wishing to see the book in print and in the hands of anyone, lawyer Mervyn Griffith-Jones called no witnesses to support his argument (as no one agreed to stand for the prosecution) and merely suggested that the book had no literary merit. The defense, led by Gerald Gardiner (who would a mere four years later become Labour Lord Chancellor), had rather a different angle. He stated that the book did have merit, that Lawrence wasn’t simply writing smut, but attacking the “impersonality of the industrial age and loss of personal relationships… he was extolling the life-giving importance of romantic and sexual intimacy” (The Telegraph). Gardiner called 35 witnesses to his side – big wigs in academia and literary worlds. He even had a Bishop – the Bishop of Woolwich, who wrote that, though Lawrence was not a Christian himself, he was “portraying the act of sex as something valuable and sacred – as an act of communion” – he went so far as to say that Christians could easily read this title.

Let’s face it… Griffith-Jones did not stand a chance.

The trial began on October 20th, 1960 in the Old Bailey’s Court No. 1. The jury held nine men and three women, and though the judge offered the defense to remove the women from the jury and the court, Gardiner refused and wished the women to stay. The entire trial lasted only 13 days (ending on November 2nd), and deliberation lasted only 3 hours. Penguin Books and Lady Chatterley’s Lover came out on top. Fifteen minutes after Penguin Books was found not guilty, Foyle’s bookshop in London had taken in orders for over 3,000 copies. On November 10th, 200,000 copies sold. As the Telegraph muses, “The result of the trial was an instant liberalization of attitudes toward publishable material. But its impact went much further. It started the process of breaking down taboos around sex – a movement that would culminate in the sexual liberation of the 1970s – and it changed the stuffy and outdated prism through which the class system was viewed” (The Telegraph).

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves, and we are so glad that we have the ability to report on this case, and celebrate the fact that due to this novel, due to this trial, we all live in a more liberated and free world.