The Counter-Reformation began with the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and lasted a full century, until the close of the Thirty Years’ War (1648). The movement sparked conflict all over Europe, challenging the very foundations of people’s daily lives. As nationalism fermented, states like Venice began to assert their autonomy–and the Catholic Church often took drastic measures in response. In the case of cleric and statesman Fra Paolo Sarpi, they even hired a hitman. Though Sarpi consistently stood up to the Church in an official capacity, he also chose to publish his greatest work, The History of the Council of Trent, under a pseudonym.

A Complicated Relationship with the Church

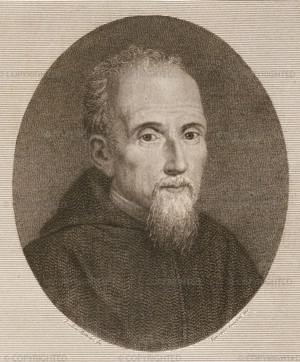

Paolo Sarpi was born in Venice on August 14, 1552. He entered the Servite order in 1566 and was eventually assigned to Mantua, then Milan. He was reassigned to 1588 after a brief stint in Rome to address business related to reforming the Servite order. Sarpi proved an adept scholar and lawyer. In 1601, the Venetian Senate recommended him for the bishopric of Caorle, but the papal nuncio declined. He alleged that Sarpi had denied the immortality of the soul and controverted Aristotle’s authority. This would not be the last accusation of heretical behavior levied against Sarpi. The following year, Sarpi made another bid at the bishopric, but this time Pope Clement VIII himself took offense; Sarpi was known to correspond with heretics, which wasn’t fitting behavior for a church official.

Furthermore, Sarpi had already appeared before the Inquisition in both 1575 and 1594. He would be questioned again in 1607. Sarpi advocated Protestant worship in Venice, as well as the establishment of a Venetian free church autonomous of the Catholic Church. He even admitted that he disliked saying Mass and avoided it whenever he could. Sarpi lived by two maxims, “God does not regard externals so long as the mind and heart are right before Him” and “I never never lie, but I do not divulge every fact to everyone.” By the end of his life, Sarpi had come to favor the Calvinist Contra-Reformists and rejected religious dogma.

Furthermore, Sarpi had already appeared before the Inquisition in both 1575 and 1594. He would be questioned again in 1607. Sarpi advocated Protestant worship in Venice, as well as the establishment of a Venetian free church autonomous of the Catholic Church. He even admitted that he disliked saying Mass and avoided it whenever he could. Sarpi lived by two maxims, “God does not regard externals so long as the mind and heart are right before Him” and “I never never lie, but I do not divulge every fact to everyone.” By the end of his life, Sarpi had come to favor the Calvinist Contra-Reformists and rejected religious dogma.

Embroiled in the Counter-Reformation

In March, 1605, Pope Clement VIII died. His successor, Pope Paul V, had a different attitude toward papal prerogative and exerted even more rigorous authority over the government. The Venetian government responded by attempting to restrict the Pope’s power. The conflict came to a head in January, 1606, when the papal nuncio delivered a brief that demanded the Venetians’ unconditional submission to papal authority. Rather than comply, the Venetian senate promised protection to all ecclesiastics who would defend the republic with their counsel. Sarpi stepped up, penning a memoir that outlined how the Venetians could respond to the censures. The document was so well received that Fra Sarpi was made canonist and theological counsellor to the republic.

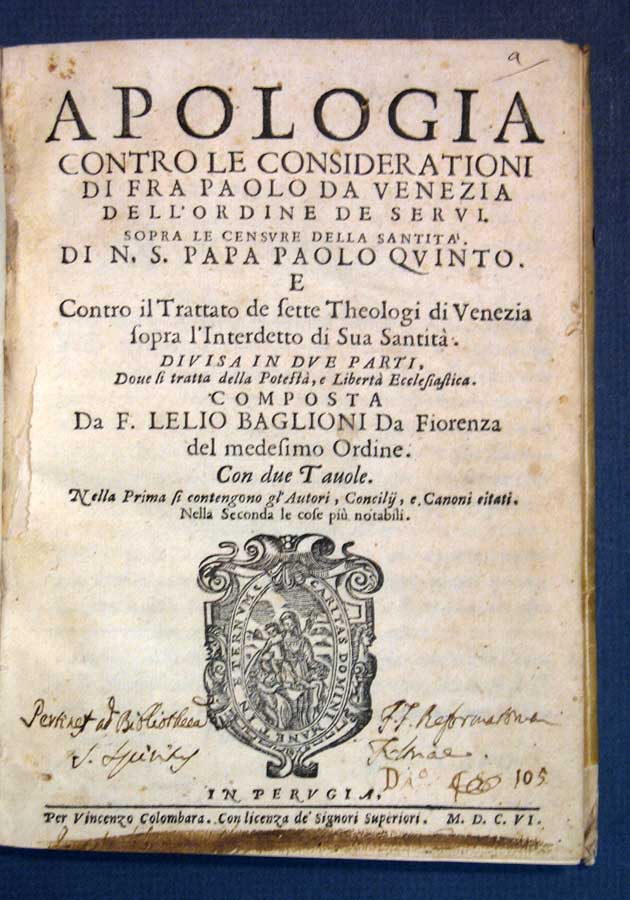

Writing as Paolo Anafesto, papal diplomat Antonio Possevino defended Pope Paul V’s interpretation of ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

In April, the Pope summarily excommunicated all Venetians. Sarpi again entered the controversy, an unprecedented move for someone of his stature. He openly argued that the power of the clergy should be secondary to the power of the state. Sarpi first republished the anti-papal republican opinions of canonist Jean Gerson (1363-1429). He also anonymously published Risposta di un Dottore in Teologica, which was promptly added to the Church’s index of banned books. Cardinal Bellarmine roundly lambasted Gerson’s works, and Sarpi responded with an Apologia. By this time, Sarpi was censor of all materials written in defense of the Venetian republic, and multiple tracts either inspired or controlled by him were published in quick succession. Only the Jesuits, the Theatines, and the Capuchins really abided by the papal decrees and were expelled from Venetian territories; the rest of Venice simply continued business as usual, and

The Catholic powers in France and Spain had tried to avoid becoming embroiled in Italian affairs, but they finally had to step in. They arranged a weak compromise in 1607: the Church acknowledged that interdicts and excommunications had lost their force. This admission did little to mitigate the animosity between the Church and the state of Venice. Indeed, the Church actually commissioned an assassination attempt on Fra Sarpi. They hired Rotillo Orlandini, a brigand and unfrocked friar, along with his two brothers-in-law to kill Fra Sarpi for 8,000 crowns. But the plot was discovered, and the would-be assassins were taken into custody before they could follow through.

On October 5, 1607, however, Sarpi was stabbed fifteen times with a stiletto and left for dead. His attackers returned to papal territory in what was described as a “triumphant march.” The enthusiasm of papal authorities was quashed when Sarpi survived the attack, but the failed assassins eventually settled in Rome and received a pension from the Viceroy of Naples. Their leader, Poma, said that he’d committed the crime for religious reasons. Sarpi would continue to be the subject of assassination plots for the rest of his life, and he occasionally considered relocating to England.

Instead, he passed his years quietly at the monastery, preparing state papers and pursuing scientific studies. He corresponded with a number of prominent scholars, including Galileo Galilei, and his documents suggest that he first encountered a telescope in November, 1608–perhaps before Galileo. The following year, the Venetian government had a telescope on approval for military use. Sarpi advised them to decline it, anticipating Galileo’s superior model. Sarpi also claimed to have anticipated William Harvey’s discovery of the human circulatory system, but the only anatomical discovery that can definitively be attributed to Sarpi is the contractibility of the iris.

The History of the Council of Trent

In 1619, Sarpi anonymously published Istoria del Concilio Tridentiro. It was printed in London under the pseudonym Pietro Soave Polano (an anagram of “Paolo Sarpi, Veneto,” with an extra “o”). Sarpi never admitted authorship during his lifetime, even under pressure from Louis II of Bourbon, the Prince of Conde. Sarpi’s editor, Marco Antonio de Dominis, was soon accused of falsifying parts of the text, but a look at Sarpi’s own manuscripts show that Dominis’ changes were minor. Nathaniel Brent published a translation, The History of the Council of Trent, in 1629. It would also be translated into French and German. The book presents an unofficial history, one that’s clearly hostile toward the papacy. Sarpi addressed ecclesiastical history as a matter of politics, so his work was especially popular among Protestants. John Milton even called Sarpi “the great unmasker.”

In 1619, Sarpi anonymously published Istoria del Concilio Tridentiro. It was printed in London under the pseudonym Pietro Soave Polano (an anagram of “Paolo Sarpi, Veneto,” with an extra “o”). Sarpi never admitted authorship during his lifetime, even under pressure from Louis II of Bourbon, the Prince of Conde. Sarpi’s editor, Marco Antonio de Dominis, was soon accused of falsifying parts of the text, but a look at Sarpi’s own manuscripts show that Dominis’ changes were minor. Nathaniel Brent published a translation, The History of the Council of Trent, in 1629. It would also be translated into French and German. The book presents an unofficial history, one that’s clearly hostile toward the papacy. Sarpi addressed ecclesiastical history as a matter of politics, so his work was especially popular among Protestants. John Milton even called Sarpi “the great unmasker.”

Sarpi argued in The History of the Council of Trent that the settlement wasn’t intended to foster compromise, but rather to incite further conflict. Critics have never denied the literary merits of Sarpi’s masterpiece, but they do acknowledge the numerous liberties Sarpi took with history (as did Cardinal Pallavicini, who refuted Sarpi’s history on behalf of the Catholic Church). Historian Hubert Jedin was particularly critical of Sarpi’s scholarship, but it has since come to light that the cleric probably used sources that haven’t survived.

Related Posts:

Astrology, Astronomy, Potato, Po-tah-to?

The Millerites and the Great Disappointment

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.