In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Juliet says, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” In Numerous authors have taken that sentiment to heart, choosing to publish under pseudonyms for a host of reasons. Charles Dickens famously wrote as “Boz,” and Samuel Clemens is better known as Mark Twain. Here’s a look at three more overlooked authors who also took pen names.

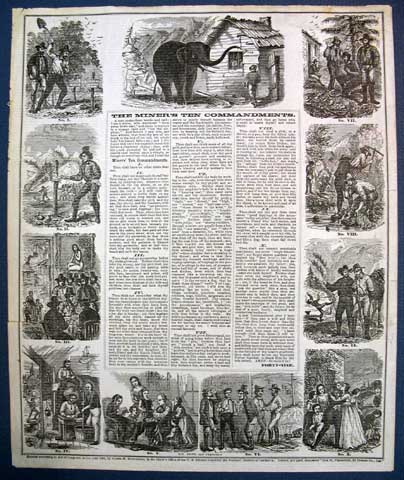

James Mason Hutchings, AKA “Forty Nine”

Born in England, James Mason Hutchings immigrated to the United States in 1848. He headed to California to find his fortune during the Gold Rush. In 1853, he published “The Miner’s Ten Commandments” under the pseudonym “Forty Nine.” Though he indeed struck it rich, Hutchings lost everything in a bank failure. He would later rebuild with a career in publishing. However he’s known not for his contributions to publishing, but for his promotion of Yosemite. Hutchings came to the region after reading Lafayette Bunnell’s evocative description of waterfalls in the region.

On July 5, 1855, Hutchings set out on one of the most historic trips to the area: he led the second tourist expedition into Yosemite (the first, led by Robert C Lamon, occurred in 1854, but there’s no known written record). Hutchings had been one of the earliest settlers in the area, and his Hutching’s Illustrated California Magazine did much to publicize the natural wonders of Yosemite. And in 1869, Hutchings hired John Muir–at the time an itinerant sheepherder–to build a sawmill on park land. Muir would become Yosemite’s greatest champion.

When Yosemite was dedicated as a state park in 1864, Hutchings refused to leave his land. Essentially a squatter, he alleged that preemption laws meant he was entitled to 160 acres of land in the valley. The case dragged on for years and went all the way to the US Supreme Court, which was unswayed by Hutchings’ argument. He would not get his land, though he did get a generous payment from the state. That satisfied him only temporarily. Hutchings continued to push legal limits, constantly challenging the prohibition of constriction of buildings on public lands. By 1875, Hutchings’ demands and arguments had worn thin; he was banished from Yosemite Valley altogether.

Metta Victoria Fuller Victor, AKA “Seeley Regester”

Metta Victoria Fuller Victor, the wife of publishing pioneer Orville James Victor, broke new ground herself with the publication of The Dead Letter (1864). The novel, which Victor published as Seeley Regester, is considered the first detective novel in the United States. Prior to that, Victor had penned Alice Wilde (1860), an early dime novel. And her abolitionist novel Maum Guinea, and Her Plantation “Children” was read and enjoyed by Abraham Lincoln himself. Victor frequently used pseudonyms, including Corrine Cushman, Eleanor Lee Edwards, Walter T Gray, and Rose Kennedy.

Victor proved an extremely prolific author, writing poetry, fiction, short stories, social issue novels, and even cookbooks. She’s notable for her adaptability; while other writers would fall out of fashion, Victor would adapt her style or genre to remain relevant. Thus, her earlier works are more sentimental, but she happily made her stories more sensational as public demand shifted. Her inventiveness drew attention from The New York Weekly, which offered Victor a $25,000 contract for the exclusive rights to her stories for five years. Such an income was quite impressive for the time period–consider, for instance that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a rockstar of his time, earned about $3,000 in eighteen months (between roughly July 1835 and January 1837).

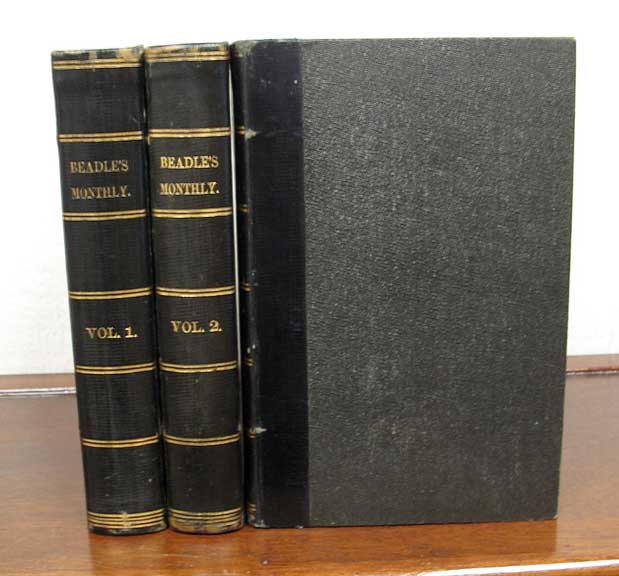

When Victor’s contract with The New York Weekly expired, she worked mostly for Beadle & Adams, still using pen names. Eventually her husband would also work at Beadle & Adams as an editor. He became one of the most respected editors in the dime novel business, making the Victors a true literary power couple of the era. Despite Victor’s multitude of contributions to fiction and literature, she remains relatively unknown today.

William Taylor Adams, AKA “Oliver Optic”

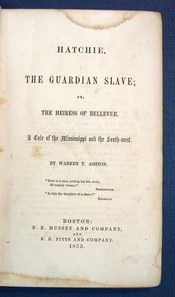

While the majority of authors who adopt pseudonyms prefer to hide their true identities, William Taylor Adams never denied responsibility for his books and stories. On the contrary, Adams frequently used his real name on the title page or at the end of the preface. Though his favorite nom de plume was Oliver Optic, Adams also used Warren T Ashton, Gayle Wintertown, Brooks McCormick, Irving Brown, and Clingham Hunter, MD. By the end of his career, he’d published 126 novels and over 1,000 stories.

When Adams published his first work, Hatchie, the Guardian Slave, in 1853, he’d been teaching in Boston Public Schools for over a decade. The book met with only moderate success, but Adams persevered. His effort paid off two years later with The Boat Club. The book was so successful, Adams decided to expand it into a series of six volumes. From then on, Adams would often write multi-volume series. Adams also acted as editor of Oliver Optic’s Magazine, Our Boys and Girls starting in 1867. It grew to be the most popular juvenile magazine in the United States.

Adams’ works were, for the most part, enthusiastically received by children and critics alike. Both action packed and lively, they still imparted moral lessons. Only Louisa May Alcott openly disapproved, possibly out of jealousy. In her “Eight Cousins,” the character Mrs. Jessie criticizes her son’s reading material for its use of slang and focus on lowlifes like bootblacks and newsboys. She says, “I have read about them…I am not satisfied with those optical delusions, as I call them now.” Adams responded line by line, and the two authors never put aside their animosity for one another.

Unfortunately Adams would later draw ire from the American Library Association. At the annual conventions of 1876 and 1879, the ALA debated the value of “sensational” fiction like that of Adams, and for some time Adams’ works were not allowed in some public libraries. Modern critics and scholars view Adams as a true pioneer in juvenile fiction. When he began writing for children, the usually available stories were the moralistic tales of the Sunday School library, books by Jacob Abbot, and others of that ilk. These tales were hardly appealing to little boys; they lacked relevance and vigor. Adams changed all that, writing stories that were full of action and adventure.

Regardless of what names they affixed to their publications, James Mason Hutchings, Metta Victoria Fuller Victor, and William Taylor Adams all made incredible contributions to the history of American literature.

Related Reading:

The Inimitable Boz and the Delightful Phiz

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post!.