Called both the “Great Arbitress of Passion” and insulted as “Juno of majestic size,” Eliza Haywood occupied a complicated place among her contemporaries. The incredibly prolific author wrote novels, plays, and pamphlets, and her writing incited controversy among her peers. Today scholars appreciate Haywood’s role as a feminist writer, and collectors can build an expansive and diverting personal library around her many works.

A Start on the Stage

Haywood’s origins are obscure, mainly because she gave conflicting accounts of her own life. But experts agree that she was born in or around 1693. Born Elizabeth Fowler, she first appears on the public record in 1715 as “Mrs. Haywood” in Thomas Shadwell’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens; Or, The Man-Hater at Dublin’s Smock Alley Theatre. She shared the stage with bookseller William Hatchett, who would be her companion and lover for over 20 years; the two never married, but Hatchett was the father of Haywood’s second child.

By 1717, Haywood had made her way to Lincoln Inn Fields, where she worked for John Rich. Rich had Haywood write an adaptation of The Fair Captive, but the play ran for only three nights. Rich staged the play for a fourth night, giving the proceeds to Haywood. Haywood’s own first play, A Wife to be Lett was staged six years later in 1723. She would go on to join Henry Fielding at Haymarket Theatre, staging opposition plays. In 1729, Haywood wrote Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lunenburgh to honor George II, the head of Tory opposition to Robert Walpole’s ministry.

More successful, however, was an opera based on of Fielding’s The Tragedy of Tragedies. Called The Opera of Operas (1733), Haywood’s adaptation included an important difference: it includes a reconciliation scene. By this time, George I and George II had reconciled, thanks to Caroline of Ansbach, and Haywood includes this development–along with symbols borrowed from Caroline’s grotto. These hints weren’t lost on Haywood’s audience, and they signaled her shift in politics to support the Tories. Fielding, however, kept up his oppositional activities, and Robert Walpole responded with the Licensing Act of 1737. The legislation effectively stopped all new plays from being produced, leaving Haywood, Fielding, and their contemporaries to pursue other authorial genres.

Amatory Fiction and Parallel Histories

By this time, however, Haywood had already exhibited talent in a variety of genres. Throughout the 1720’s, she wrote the kinds of novels that would today be called “bodice rippers.” Haywood made her debut with Love in Excess; Or, the Fatal Enquiry (1719-1720), which offered a surprisingly positive view of a fallen woman. The novel was published in two separate volumes thanks to the economy of the time; authors were paid flat fees for their work, rather than royalties, so it behooved Haywood and her contemporaries to publish their works in multiple volumes.

Watch an Oxford University lecture on Haywood’s Love in Excess and Defoe’s novels>>

Had she gotten royalties for Love in Excess, she’d have been well off, indeed. The book was reprinted six times over the next decade. To advertise subsequent editions, Haywood’s colleagues wrote in praise of Haywood’s seductive writing. Richard Savage exclaimed that her “soul-thrilling accents all our senses wound” to promote the second printing of the novel’s first edition, and James Sterling wrote in 1725 that Haywood was the “Great Arbitress of Passion.”

Haywood continued penning novels for the next three decades. She, Aphra Behn, and Delarivier Manley came to be known as “the fair triumvirate of wit,” and Haywood contributed fully to the literary life of her era. Her Adventures of Eovaii: A Pre-Adamitical History (1736) mocks the idea that a woman should barter her virginity to obtain a place in society, later popularized by Samuel Richardson in Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740). Henry Fielding would also satirize Richardson’s novel with An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews (1741).

Haywood’s writing evolved considerably over time, as did her evaluations of marriage and relationships between women and men. The History of Betsy Thoughtless (1751) is considered the first novel of female development written in English, and it’s also unusual for its focus on marriage, rather than courtship, which became popular and reached a peak in the nineteenth century with authors like Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë.

Pamphlets and Periodicals

Along with her thrilling novels of the 1720’s, Haywood also published a number of titillating pamphlets about the life and supposed talents of the deaf and mute Duncan Campbell. Campbell allegedly had a gift of prophecy, which was attributed to numerous supernatural sources. Haywood published A Spy Upon the Conjurer (1724) and The Dumb Projector (1725). It’s also conjectured that Haywood wrote, along with Daniel Defoe and William Bond, The History of the Life and Adventures of Mr. Duncan Campbell (1720).

In 1744, Haywood undertook a new and impressive task. She began issuing The Female Spectator, the first periodical written by women, for women. It was Haywood’s response to The Spectator, an incredibly popular periodical issued by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, and she followed the example of John Dunton’s Ladies’ Mercury. In The Female Spectator, Haywood wrote using four personas, rather than her own name. She issued four volumes of the periodical between 1744 and 1746. When Haywood published her conduct book The Wife a decade later, she originally published under the “Mira” persona she’d used in The Female Spectator. But The Wife’s companion piece, The Husband was published shortly thereafter under Haywood’s own name.

Haywood again ran into trouble for expressing her political views with The Parrot (1746) and A Letter from H__ G__g, Esq (1750). She created fictional accounts of the exploits of Bonnie Prince Charlie, which proved an ill advised topic to address on the heels of the Jacobite uprising. A stack of the pamphlets was found in her home, and Haywood was arrested and charged with seditious libel–as was Hatchett.. Haywood argued that she hadn’t written or printed the pamphlets, but that someone had left them at her home. Neither Haywood nor Hatchett ever went to trial.

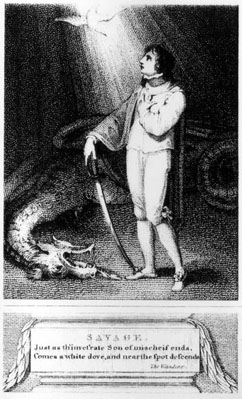

Haywood’s Appearance in Pope’s Dunciad

Ever interested in politics, Haywood published a series of parallel histories, notably Memoirs of a Certain Island, Adjacent to Utopia (1724) and The Secret History of the Present Intrigues of the Court of Caramania (1727). In the former, Haywood not only picks a fight with her contemporary Martha Fowkes, but she also not so subtly alludes to her one-time affair with Richard Savage–and to Savage’s lack of proper pedigree. Savage claimed that he was the illegitimate heir of a wealthy family, and many details of his claims have been corroborated. He also murdered a man but managed to dodge the death penalty.

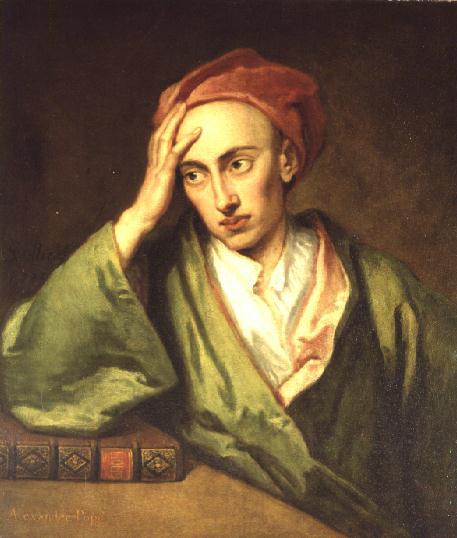

Savage’s purported lowly origins only served to heighten his notoriety. A poet (and the father of Haywood’s first child), Savage became a famous figure, so much so that Samuel Johnson deemed him worthy of biography. The success of Johnson’s Life of Savage (1744) pushed both Johnson and Savage to even greater prominence. Savage’s celebrity would soon present a challenge for Haywood. Intimately familiar with the hacks of Grub Street whom Alexander Pope so openly despised, Savage fed Pope plenty of details for the Dunciad Variorum (1729). Savage undoubtedly aided Pope in excoriating Haywood, who unabashedly wrote to feed her two children. Pope found Haywood absolutely “vacuous.” He refers to her as the “phantom priestess,” an allusion to Fantomina and calls her “Juno of majestic size, with cow-like udders, and ox-like eyes.”

Richard Savage

Savage’s sycophancy paid off with years patronage from Pope, and he enjoyed several years of prosperity. But one by one, his patrons dropped away until Pope was the last remaining. In 1743, even Pope wrote to cut off ties, and Savage soon found himself penniless. He died in debtor’s prison. Though at the time Savage enjoyed a strong reputation as a poet, today his works are mostly overlooked in favor of his more illustrious contemporaries.

Unfortunately for Haywood’s legacy, for centuries she was remembered primarily for her appearance in the Dunciad. It’s only in the last several decades that scholars have begun to recognize Haywood’s varied contributions–and more remain to be discovered, since Haywood so frequently published anonymously. Today, experts see Haywood’s novels as a pivotal transition between lurid novels like those of Aphra Behn and the more plain spoken works epitomized by Frances Burney.

For collectors, Eliza Haywood offers limitless opportunities to build a rich collection. A truly prolific author, Haywood could keep the dedicated completist busy for a lifetime! And her fascinating relationships with other authors offer numerous directions to extend a collection.

Further Reading

Williams, Kate. ‘The Force of Language, and the Sweets of Love’: Eliza Haywood and the Erotics of Reading Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa. Lumen: Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies/ Lumen:travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d’étude du dix-huitième siècle, vol. 23, 2004, p. 309-323

Wilmouth, Traci. A Savage Spy: The Role of Richard Savage in Composing Pope’s Dunciad. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 2007.