“Is it tolerable that besides being robbed and rifled, an author should be forced to appear in any form – in any vulgar dress – in any atrocious company – that he should have no choice of his audience – no controul [sic?] over his distorted text – and that he should be compelled to jostle out of the course, the best men in this country who only ask to live, by writing?”

-Charles Dickens, to Henry Austin (May 1, 1842)

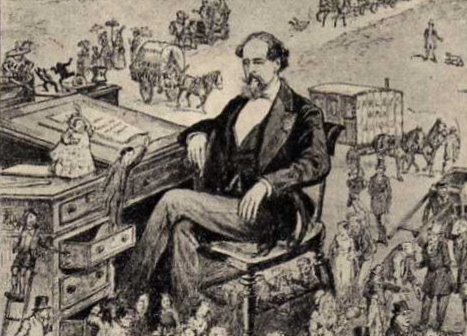

By the time Charles Dickens made his first visit to America, the country was deeply embroiled in a publishing battle with Britain. His repeated pleas for international copyright law would eventually spark the “Dickens Controversy” and bring new accountability to the world of American publishing.

A Legal Loophole

In Dickens’ day, American copyright law provided no protection for non-citizens’ intellectual property. The result hit both British and American authors in the pocketbook: British authors received no royalties on pirated editions of their works, and their authorized editions were hardly appealing at many times to price of the pirated copies. Meanwhile, American authors like Edgar Allan Poe, Washington Irving, and Walt Whitman lost money because American readers would purchase 25-cent pirated British literature instead of one-dollar American books.

While such a publishing problem might seem inconsequential in the grand scheme of foreign relations, it actually caused significant tension. American publishers sent employees to scour the docks of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, in hopes of intercepting manuscripts from popular authors that were bound for pirated editions. Meanwhile, British officials frequently confiscated as contraband American pirated copies of British books.

Thus Dickens faced quite a copyright conundrum. The pirated editions severely cut into his profits, but they also increased his circulation and popularity, leading to more demand for his work. But ultimately Dickens knew that more rigorous copyright laws would benefit authors on both sides of the Atlantic. He began openly advocating international copyright law. By the time Dickens arrived in the United States for the first time on January 22, 1842, he already planned to enlist American authors to support his cause.

A Triumphant Arrival in Boston

Dickens’ fans in Boston greeted him like a rock star. He later wrote to a friend, “there never was a king or Emperor upon the Earth, so cheered, and followed by crowds.” Thanks to all those pirated copies of Dickens’ novels, the author had an incredible fan base in the United States. Dickens clearly loved the attention and adulation. He could also identify with the American ideals of democracy, liberalism, and equality. He’d pulled himself from poverty to become a celebrated author, personifying those ideals. And the American press glommed on to Dickens’ story. One paper called him “Boz, the gay personification of youthful genius on a glorious holiday.”

Dickens was received by preeminent scholars and authors of Boston, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Richard Henry Dana, and Daniel Webster. On February 1, 1842, Dickens was the guest of honor at a “Young Men of Boston” dinner. He used the event to give his first speech to an American audience on the subject of international copyright law. This move proved poorly calculated; while Dickens had expected to receive support from fellow authors, he instead encountered resistance. America’s economy was flagging, and authors were reluctant to come across as demanding more money from the reading public.

Public Opinion Turns for the Worse

Dickens had also underestimated the power and priorities of the American press. Countless newspapers filled their pages with free British content, so international copyright law posed a significant threat to their profits. The newspapers immediately accused Dickens of being a “hired agent” for Britain, a mercenary out to fleece the American public. Dickens’ reputation was quickly tarnished.

Even Walt Whitman, who’d always been fascinated with Dickens, got in on the action, publishing “Boz’s Opinion of Us” in the New York Evening Tattler, where he was the editor. The paper ran a forged letter, supposedly from Dickens, outlining the “dark spots of American character.” Even though Whitman actually defended Dickens’ words, praising passages of the letter, the whole episode deeply damaged Dickens’ image. The editor of one New York newspaper reprinted the letter and said, “it will ruin Mr. Dickens’ personal popularity altogether with us.”

Dickens Strikes Back

Although Dickens was initially quite taken with the United States, his account of the trip, “American Notes,” was relatively dry. He was harsh, however about slavery and the “abject state” of the American press. It was with Martin Chuzzlewit that Dickens really lashed out. The eponymous protagonist, a young man, travels to America to seek his fortune, only to be disappointed with American customs, manners, and publishing. Martin Chuzzlewit was published (unauthorized, of course) by the very papers that Dickens insulted in the novel.

Soon after, Dickens gave up lobbying for international copyright law. He realized it was a lost cause. But he didn’t give up his position entirely. Dickens stopped negotiating with American publishers for advance sheets of his novels, effectively removing their advantage of printing his books first. While this refusal wasn’t controversial, it was extremely unusual for the time period.

Finances Spur a Return

By the 1860’s, Dickens was an established celebrity. By all accounts, he should have been quite comfortable financially. But after much marital strife, Dickens’ wife, Catherine had been removed from the Dickens’ Rochester estate. A divorce would have sullied Dickens’ image, so he settled for relocating his wife to London and giving her a monthly stipend. And Dickens was still supporting his adult children–all six of his surviving sons were still receiving support from him by the mid-1860’s, despite being of age to support themselves.

Dickens’ resources were stretched thin. He wrote to his sister-in-law Georgiana, “Expenses are so enormous, that I begin to feel myself drawn towards America, as Charles Darnay in Tale of Two Cities is drawn toward Loadstone Rock, Paris. He believed enough time had passed that the American public would have forgotten about the publicity debacle of his first visit to the States.

Meanwhile, Dickens had perfected his readings, and British audiences flocked to see him perform. American theatre managers promised a second American tour would be even more lucrative than the first. They were correct. Dickens made £38,000 for 76 readings. His managers strutted around with paper bags full of cash. When Dickens passed away, the profits from this American tour constituted a full twenty percent of his estate.

An Unexpected Move

In 1867, Dickens made a bold proclamation. He announced that Fields, Osgood, and Co, the publishers who’d sponsored his tour, would have exclusive rights to his next novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. This was a truly unprecedented maneuver, and it spurred discussions that have since become known as the “Dickens Controversy.” Dickens knew that he would never stop piracy of his works altogether, but he made an impassioned moral plea to the American public to buy authorized editions.

The tactic–perhaps surprisingly–worked quite well. Even the most notorious pirating firms were forced to reconsider their practices in light of Dickens’ campaign. Alas, Dickens passed away before finishing The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and the changes he promoted for international copyright law weren’t adopted until 1891. But Dickens contributed to a new era of cultural balance between Britain and the United States.

Related Posts:

Charles Dickens Does Boston

Irving and Dickens: The Authors Who Saved Christmas

Why Did Charles Dickens Write Ghost Stories for Christmas?

The Two Endings of Charles Dickens’ ‘Great Expectations

Oscar Wilde: Dickens Detractor and “Inventor” of Aubrey Beardsley

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.