Dr. Blake examines the backside of a broadside, where we often find clues about the document that we can’t glean from the text. This item, which the Folger acquired from Tavistock Books, is the Edinburg edition of the “Regicides” broadside (1660), wherein Charles II commands those involved in the death of Charles I to present themselves, “being deeply guilty of that detestable and bloody Treason.”

This week we’re pleased to welcome our friend and colleague from Rare Book School, Dr. Erin Blake. Dr. Blake is the Curator of Art and Special Collections at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. She was kind enough to sit down with us to talk about her journey to the Folger and her evolving role as the curator of “anything that’s not a book or a manuscript.”

TavBooks: Tell us a bit about your career path. What drew you to art history? And what brought you to the Folger?

Dr. Blake: I started out as a history major and discovered that I really liked studying objects as part of history, as evidence. And art history is where you actually get to delve into that, so I did a double major in history in art history. When I got my PhD, I didn’t want to do that typical art history thing where you pick an artist no one else has “done” before. Instead I ended up studying topographical views designed for the zograscope, which was a viewing device that gained popularity around 1750 in England. You look through a lens and mirror arrangement to get a three-dimensional view of a scene.

This colored print, from the University of Exeter, shows a zograscope in use.

Although these images were often topographical, they weren’t really maps. Nor were they really art. But when the British Museum split into the British Museum and the British Library, the zograscope images went to the map library. The art people didn’t study them because they weren’t art, and the map people didn’t study them because they weren’t maps. So here I was, this art person looking at pictures in a map library!

It was only a matter of time before I began exploring the world of special collections libraries. I always knew that I’d wanted to work in a library, rather than a museum, and that I didn’t want to be an art history professor. When the Folger advertised for a curator, it seemed like the perfect opportunity.

TavBooks: Your original title was Curator of Art, and that has been expanded to include special collections. What are your responsibilities now? And how has your position evolved since you began?

Dr. Blake: My job here is to make the items in our collection available to scholars as primary sources and to acquire new items that complement the research needs of the collection. Our interests in that regard are unusual for art. Museums want rare, pristine, first state prints, but we’d rather have the more common ones. The version of an item most seen and used by people is of most use to researchers. When Mr. and Mrs. Folger were building their collection, they were also interested in things that had been written in, written on, things that had been used. When people come to study the history of readership, that record helps us determine what was important to people as they looked at books and prints.

When I started at the Folger, I was in charge of art. The objective definition of art is “anything that isn’t a book or manuscript.” And special collections is lots of stuff that isn’t really art by other people’s definition. Here, for instance, that includes ephemera like playbills, scrapbooks, and even strange objects.

TavBooks: What’s your favorite item in the collection? Have you discovered anything that inspired you to do more in-depth research for yourself?

Dr. Blake: It’s interesting to explore the degree to which there are fetish objects associated with Shakespeare. For example, there are items made out of Shakespeare’s mulberry tree. The tree grew in his garden, and he supposedly planted it. During the eighteenth century, people would make pilgrimages to Shakespeare’s home. They’d take slips of the tree and use them to grow their own at home.

A 1905 auction catalogue featured a photograph of this “tea-caddy made from the mulberry tree planted by Shakespeare” and called it “an undoubted genuine relic, having Sharp’s own stamp on it.” Thomas Sharp was the most recognized maker of mulberry souvenirs, stamping his products with “Shakespeare’s wood.” This box has no stamp, but rather a place where a stamp appears to have been scraped away.

Eventually the man who owned the property grew tired of the constant stream of visitors, so he cut down the tree and sold it for firewood. But the people who bought it didn’t use it for firewood. Instead, it was made into a wide variety of souvenirs and talismans, such as bookmarks and figurines. We obviously can’t definitively determine whether each of these items actually originated from the tree in Shakespeare’s yard–at least not without destroying the objects themselves–but what’s important is that the people believed these items were associated with Shakespeare.

But my favorite items are the unexpected ones. One is a book of caricatures by the artist Sem. Because of the way the Folger collection was unpacked in 1932, items were sorted into books and manuscripts, or prints and drawings. This volume is more like a scrapbook. The pages have really detailed watercolor caricatures of people from the theater scene, along with handwriting samples from each person, often letters written to the collector who created the book. There’s also a Shakespeare quote with each character. The book was marked “A.L.S.” — autograph letters, signed — and placed with the manuscripts because of the handwriting samples, so it ended up being catalogued as about 60 separate manuscripts. People never knew significant art was there, but this year a summer intern is making preliminary records for the drawings.

TavBooks: How has our perception of art changed since Shakespeare’s time?

Dr. Blake: The status of artists has changed quite a bit, a shift which really started around Shakespeare’s time. There was a movement to elevate artists to the status of intellectuals; art was not a craft, and not a trade. But for a long time art sat astride two worlds. The people who did theater scenery might also show at the Royal Academy.

For some time, book illustrators were excluded. Illustrations were not seen as fine art. But we find a whole lot of primary source information in book illustrations. But there’s been a shift in the past ten to fifteen years. Researchers used to come to the Folger and say, “I’ve written a book. Now I need illustrations to go with it.” Now it’s the other way around. They say, “I’m writing a book, and I need to examine the visual evidence.” We’ve learned that evidence can also be visual, not just verbal.

The collection includes many drawings and sketches of costumes and scenery, such as this one. Charles Hamilton Smith and his daughter, Emma drew these watercolor drawings and tracings of theatrical costumes, banners, shields, and arms especially for Charles Kean’s productions at the Princess and Haymarket theaters.

TavBooks: What do you love about working at the Folger Shakespeare Library?

Dr. Blake: One of the great things about working here is the flexibility for people to do things they particularly enjoy. I’ve become much more involved in descriptive cataloguing. I’ve been helping to develop a new edition of guidelines for libraries to catalogue pictures. The manual, Descriptive Cataloguing of Rare Materials (Graphics), will be published later this year.

TavBooks: Why are you particularly interested in descriptive cataloguing?

Dr. Blake: That goes back to why I was so interested in working in a library. When I was doing dissertation research in the 1990s, web-based online catalogues were brand new. I was doing research at Northwestern when they got their new online system, and I noticed that one of the tabs on the search results was “Staff View.” I wondered what that was, so I clicked on it. It was an encoded version of all the information displayed elsewhere in the record. All this information was hidden from scholars, but it meant much more sophisticated searching strategies for those who knew.

I’ve always been interested in systems, how they’re constructed, and how they work. What I enjoyed was building a database, seeing how things broke down, and figuring out how to make the data accessible to the people who needed to use it. The methodology of descriptive cataloguing certainly fits into that. And I wanted to help create a system for something that’s often perceived as subjective.

TavBooks: You’ve also done some interesting work in the field of preservation. Tell us a little bit about your discoveries.

Dr. Blake: We received an NEH grant for developing a sustainable preservation environment with the help of the Image Permanence Institute. The long-received wisdom was that the best way to maintain your library was a straight-line temperature and relative humidity: 70 degrees Fahrenheit and 50% RH. It turns out that this guideline, which had long been the convention, was actually a provisional guideline that wasn’t meant to be widely applied. In most cases cooler and dryer is actually better. But there’s also a greater range of acceptable conditions. As an analogy, think of flexing a piece of cardboard: it has quite a bit of give; it’s only if it’s bent past a certain point that it gets permanently creased.

For libraries, maintaining an absolute flat line at 70 degrees and 50% RH is expensive. It’s also damaging to the environment. So our goal was to define more flexible parameters and make preservation more sustainable. If we’re preserving a collection, but destroying the environment, then why bother? Ultimately we upgraded key air handlers to maintain a cooler, dryer environment while consuming less energy. We also now shut off air handlers for underground spaces at night; the conditions are relatively stable, and books don’t require constant air circulation. We did face a problem with humidity in the summer, but have figured out how to handle that.

TavBooks: You’re responsible for items that are made of basically everything except paper–and probably some paper, too. What preservation challenges do you face as a result?

Dr. Blake: The most difficult things are objects that aren’t entirely one material or another, but that are made of multiple materials. A painting on wood in a metal frame…these materials expand and contract at different rates, the frame could rust, etc.

TavBooks: As a curator, you’re responsible for deciding the direction and scope of an extensive collection. Individual book collectors are also curators, albeit on a smaller scale. What advice would you offer them?

Dr. Blake: Be sure to collect something that interests you. Don’t collect because you think it will be worth money in the future. And come up with a clear theme for your collection–and stick to it! You build a strong collection around a core idea. There’s a phrase in libraries, “build to strength.” We don’t want a few random things, but the best collection of X, whatever X may be. Consider your collection as something you’re building for the future, and that you’re telling a story with your collection. What you choose to collect illustrates what’s important to you and to someone of your era.

It’s also important to document your collection and why it’s particularly interesting to you. Record when and where you got each object, and why you chose to acquire it. Otherwise, that object dies because its story isn’t being told. Ask yourself, “What else can this object tell us about people in the 21st century?”

A terrific example of a large and meaningful collection is the Babette Craven Theatrical Memorabilia collection. Mrs. Craven collected objects across all media from late eighteenth-century to early nineteenth-century England. The way she collected reflected her intention that the collection would be a legacy. It included not only prints and playbills, but also figurines and other memorabilia. Most institutions wanted only one category of items, rather than the collection as a whole. But we saw the value in the whole body of work, and our enthusiasm for the collection has inspired others to build similar legacies.

Three items from the Craven collection: Bilston enamel bodkin case of Dorothy Jordan and the Duke of Clarence (ca. 1795) (verso); enamel patch box of Dorothy Jordan and the Duke of Clarence( late 18th century); turned wooden box with a Bilston enamel portrait medallion of Dorothy Jordan(ca. 1790).

TavBooks: It seems like eventually the Folger would own a pretty comprehensive and complete collection. Has it become more difficult to find and acquire new, unique objects over time?

Dr. Blake: It seems that there’s always some private collection that’s been unexplored and no one’s paid attention to. So things are constantly coming to the market. We’re sometimes amazed that they haven’t been discovered before, but no one was looking for it!

We thank Dr. Blake for her time! If you’re in Washington,DC we also encourage you to stop by the Folger Shakespeare Library. Currently on exhibit is “A Book behind Bars: The Robben Island Shakespeare.” Nelson Mandela served eighteen years as a political prisoner at Robben Island. A fellow prisoner smuggled in a copy of the complete works of Shakespeare, and prisoners–including Mandela–signed and dated their favorite passages. The book is on display along with a series of sketches Mandela made reflecting his life in prison.

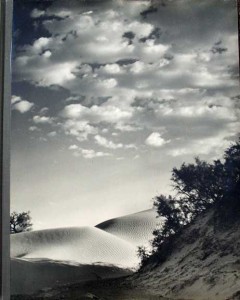

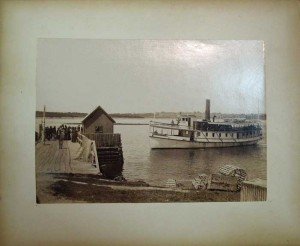

Common enemies of antiquarian books include direct sunlight, humidity, and vermin, along with substances like adhesives–and even other paper. The same holds true for antiquarian photographs and photo albums. But due to their more complex composition, these items often require even more specialized care.

Common enemies of antiquarian books include direct sunlight, humidity, and vermin, along with substances like adhesives–and even other paper. The same holds true for antiquarian photographs and photo albums. But due to their more complex composition, these items often require even more specialized care. Larger photographs can be placed into individual polyethylene bags. If you’d prefer to display them, the best approach is to attach each photograph (and the original mounting board, if present) to 100% rag acid-free mat board with a window-mat of the same material hinged to fold over it. You can use acid-free linen tape to hinge the two mats together. This way, the photograph won’t come in contact with the frame’s glass, and you’ll hide the imperfections of the original mat.

Larger photographs can be placed into individual polyethylene bags. If you’d prefer to display them, the best approach is to attach each photograph (and the original mounting board, if present) to 100% rag acid-free mat board with a window-mat of the same material hinged to fold over it. You can use acid-free linen tape to hinge the two mats together. This way, the photograph won’t come in contact with the frame’s glass, and you’ll hide the imperfections of the original mat. Albumen prints are a special case. They tend to curl when removed from deteriorating albums. To combat curling, you have a few different options. A number of institutions embrace the practice of hinging albumen prints on all four corners, and this is a perfectly viable option. But the American Photographic Museum uses a different approach: they slip each print into its own clear polyester envelope and attach the envelope to a mat board with a hinged over-mat. Treated this way, the photos can then be framed if desired. This technique can be used with virtually any fragile item, not only photographs but also prints, maps, and ephemera.

Albumen prints are a special case. They tend to curl when removed from deteriorating albums. To combat curling, you have a few different options. A number of institutions embrace the practice of hinging albumen prints on all four corners, and this is a perfectly viable option. But the American Photographic Museum uses a different approach: they slip each print into its own clear polyester envelope and attach the envelope to a mat board with a hinged over-mat. Treated this way, the photos can then be framed if desired. This technique can be used with virtually any fragile item, not only photographs but also prints, maps, and ephemera.