“I am become a sort of great man in my way–all but at the top of the tree; indeed there if truth be known and having a great fight up there with Dickens.”

-William Makepeace Thackeray, in a letter to his mother

Contemporary authors Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray are remembered as preeminent writers of Victorian England. The two traveled in the same social circles and were at first great admirers of each other’s work. Their daughters even grew to be close friends. But a series of literary disputes drove the authors apart. Their feud culminated in the Garrick Club affair, which resulted in a rift that would not be bridged until just before Thackeray’s death.

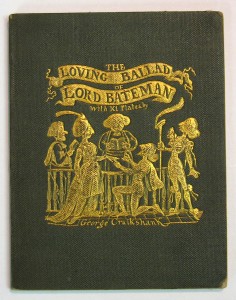

The young Charles Dickens became the darling of both critics and public with Pickwick Papers (1836-1837). Meanwhile, Thackeray slaved away as a hack writer for another decade. Despite their unequal reputations, the two authors enjoyed each other’s work. They even presumably collaborated on The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman, which was initially attributed to Dickens. Now it’s believed that Thackeray wrote the body of the book, while Dickens wrote the preface and notes.

The young Charles Dickens became the darling of both critics and public with Pickwick Papers (1836-1837). Meanwhile, Thackeray slaved away as a hack writer for another decade. Despite their unequal reputations, the two authors enjoyed each other’s work. They even presumably collaborated on The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman, which was initially attributed to Dickens. Now it’s believed that Thackeray wrote the body of the book, while Dickens wrote the preface and notes.

Finally, the publication of Vanity Fair (1847-1848) gained Thackeray the critical attention he sought and freed him from financial struggle. The novel got off to a slow start–multiple publishers rejected the first few chapters–but the novel eventually sold about 7,000 numbers per week. It made Thackeray the talk of London, though still not to the same extent as Dickens.

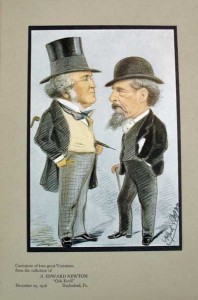

“Caricature of Two Great Victorians, Christmas Greetings for 1916” was published by Oak Knoll Press. It later used as the frontis for Newton’s popular 1918 work, ‘The Amenities of Book Collecting and Kindred Affections.’

Thackeray’s next novel, Pendennis (1849-1850) was published concurrently with Dickens’ David Copperfield, and Thackeray finally earned comparison to the Inimitable, first in North British Review and later in other critical journals. Thackeray knew that he would never equal Dickens in the eyes of the reading public, but he was happy to be equally respected and admired among critics. Dickens, however, was less enthusiastic about sharing the limelight: Dr. John Brown, a friend of both authors, noted that Dickens “could not abide the brother so near the throne.” Thackeray and Dickens would subsequently engage in a number of literary quarrels, notably the “Dignity of Literature” debate.

In 1858, the situation finally reached a head. Dickens had recently separated from his wife, and he was sensitive to public and private opinion about his choice. It especially rankled Dickens when he heard that Thackeray had repeated information about Dickens’ affair with Ellen Ternan. Thus it should come as no surprise that Dickens allowed Edmund Yates to publish an anonymous, slanderous attack on Thackeray in Household Words. Yates was a young journalist whom Dickens had taken under his wing. He was also a member of the Garrick Club, along with Dickens and Thackeray.

When Thackeray learned that Yates had written the Household Words piece, he wrote a letter demanding an apology. Upset that Yates had shared confidential conversations from the Garrick Club, Thackeray took the issue before the Garrick Club. Though Dickens had been overseas when the dispute broke, he quickly jumped to Yates’ aid, writing letters to both Thackeray and to the Garrick Club committee. But Dickens intervention did little to mitigate the situation; the committee decided to cancel Yates’ membership, and he was forbidden to set foot on Club property.

Yates did not consider the matter closed. He continued writing journal articles and pamphlets, fanning the flames of scandal. He even penned Mr. Thackeray, Mr. Yates, and the Garrick Club: The Correspondence and Facts (1859), which was predictably biased in his favor an which he had privately printed by Taylor and Greening. Finally Dickens realized that his support of Yates might damage his own reputation, and he convinced Yates to put the matter to rest.

Yates did not consider the matter closed. He continued writing journal articles and pamphlets, fanning the flames of scandal. He even penned Mr. Thackeray, Mr. Yates, and the Garrick Club: The Correspondence and Facts (1859), which was predictably biased in his favor an which he had privately printed by Taylor and Greening. Finally Dickens realized that his support of Yates might damage his own reputation, and he convinced Yates to put the matter to rest.

The feud certainly weighed on Thackeray. He admitted to Charles Kingsley, “What pains me most is that Dickens should have been his adviser, and next that I should have had to lay a heavy hand on a young man who, I take it, has been cruelly punished by the issue of the affair and I believe is hardly aware of the nature of his own offense and doesn’t even understand that a gentleman should resent the monstrous insult which he volunteered.”

But Thackeray hardly felt compelled to extend an olive branch to either Dickens or Yates. Still close friends, Thackeray and Dickens’ daughters struggled to facilitate a reconciliation between their fathers. Though they got their fathers to relax their opinions, they didn’t manage to effect a meeting between the two men. That happened accidentally, when the two authors bumped into each other on the steps of another London club. The men shook hands and parted ways. Only months later, Thackeray passed away.

Though these literary titans may have bitterly quarreled, they both left behind a rich authorial legacy. Thackeray and Dickens are both central figures in the canon of Victorian literature.