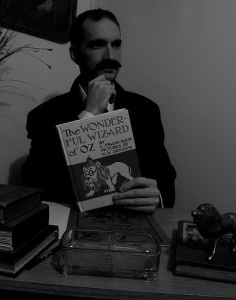

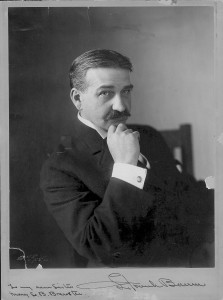

L Frank Baum is best remembered as the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), but writing was certainly not his first occupation. Baum was, like many men of his generation, a jack of all trades and a master of none; he’d pursued a number of careers–all with little success. He went to Aberdeen, South Dakota looking for a fresh start…only to find himself running a new baseball club, the Hub City Nine.

L Frank Baum is best remembered as the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), but writing was certainly not his first occupation. Baum was, like many men of his generation, a jack of all trades and a master of none; he’d pursued a number of careers–all with little success. He went to Aberdeen, South Dakota looking for a fresh start…only to find himself running a new baseball club, the Hub City Nine.

A Nascent Metropolis

When Baum arrived in Aberdeen in 1888, the town was rapidly growing, and it wasn’t much like the stereotypical frontier town. Founded in 1881, Aberdeen was populated not with farmers and cowboys, but with college educated citizens who’d come West for cheap land. They arrived by train and immediately set about reestablishing life as they’d known it back East. Aberdeen’s citizens went to local events in full dinner dress. They enjoyed champagne and other delicacies. By 1885, assessment reports show that there were 135 pianos for a town of 2,500 people. Electric lights were available the following year.

Baum and his family moved to Aberdeen because Baum’s wife, Maud desperately missed her family. Her brother, TC Gage, had already settled in Aberdeen, and her sisters lived relatively close by. Baum had read reports of the town’s burgeoning prosperity in the June 2, 1888 edition of the Aberdeen Daily News. Overly impressed, he wrote to his brother-in-law, “In your country, there is an opportunity to be somebody, to take a good position, and opportunities are constantly arising where an intelligent man may profit.” He confided that he planned to open a novelty store, “not a 5¢ store, but a Bazaar on the same style as the ‘Fair’ in Chicago…and keeping a line of goods especially saleable in that locality.”

Baum opened up Baum’s Bazaar on October 1, 1888. Over 1,000 people attended the grand opening. He’d stocked up on all kinds of luxury goods, from amateur photography equipment to sporting goods. There was no shortage of interest in his wares: the Christmas crowd numbered over 1,200. On December 3, 1888, the Aberdeen Daily News reported, “Baum’s Bazaar is an [Aladdin’s] chamber of wonders and beauty.”

Aberdeen Gets a Baseball Club

As far as Baum was concerned, Aberdeen lacked only one important thing: a baseball team. Though Baum had never been a great athlete, he’d undoubtedly played the sport casually and watched local club teams play in upstate New York. However he encountered the game, Baum was an enthusiastic “crank,” as baseball fans were then called. As soon as he settled into Aberdeen, he went about rallying support to start a club team.

Baum reasoned that the sport would be great for the community and for his business; he hoped to sell plenty of Spalding sporting equipment during the baseball season. Meanwhile, larger cities like Omaha, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Des Moines, and Sioux City already had baseball teams. Getting a baseball club could put Aberdeen on the map in a new way. The Aberdeen Daily News spoke positively, saying “Nothing creates enthusiasm like base ball, and nothing will draw a crowd so continuously as the national game closely contested and honorably played.”

Baum convinced a group of Aberdeen businessmen that the city needed a baseball club. Baum so impressed the men with his enthusiasm, they named him secretary of the club and appointed him to the constitution and by-laws committee. They named the club the Hub City Nine, a reference to Aberdeen’s nickname as the Hub City because seven rail lines converged there. The first 210 shares sold at at $10 each in three days, and the remaining 90 sold shortly thereafter. Baum also spearheaded an effort to sell advertising space on the baseball field’s back fence.

The group was so industrious and successful in their fundraising, it drew the attention of nearby communities. In the Fargo Daily Argus, baseball club manager Con. Walker complained, “The citizens of Aberdeen contributed $3,000 to their base ball team this season. The Fargo people have done nothing for the club in the last two years.” Walker entreated the town to support the home team if they wanted the club to continue and flourish.

A Promising Start

Baum and the other board members believed that organizing a league was critical to their success, so Baum headed up efforts to organize the South Dakota League. When the league was formalized on June 7, 1889, all the participating teams contributed $100. The Hub City Nine also strove to legitimize itself further by adopting the National League Rules. At the time, the rules of baseball had yet to be normalized, and the National League, Western Association, and American Association all had different rules. The National League, founded in 1876, was the oldest and most powerful of these organizations.

When it came time to recruit players, the Hub City Nine offered $50 per month, plus room and board. To sweeten the pot, club president Jewett offered a box of cigars to the first man to hit a ball over the center field fence. Baum threw in another box for the player who hit the first home run. And local grocers Thompson and Kearney promised $25 to anyone who hit a ball into the “Hit Me for $25” box on the fence where they advertised.

The National League forbade gambling or selling liquor on the premises, along with holding games on Sundays. The Hub City Nine took these rules a step further because they wanted the games to be family- and (more importantly) female-friendly. Profanity was prohibited. Both players and spectators were to treat the opposing team with the utmost respect, and “no unseemly or ungentlemanly conduct [was] allowed on the ball grounds.”

On May 29, 1889, the Hub City Nine players gathered for their first practice. The event was free to attend, and a healthy number of spectators showed up to observe the proceedings. The first game, a warm-up against Redfield, sold over 1,000 tickets. There was not enough room in the stands to hold them all! Baum later managed to get the St. Paul Indians to come to town for a game. The club raised admission to 50 cents, from 25, and though people grumbled, they still purchased tickets for the game. The Milwaukee railroad ran three extra trains to bring the fans into town. The game brought sorely needed funds back to the club.

A Baseball Feud

Indeed, the Hub City Nine games were so popular, “half as many people perched on the fence and on buildings and elevations surrounding as there were in the enclosure,” according to the Aberdeen Daily News. The paper called this a “detestable practice.” Lester J. Ives, in particular, drew the ire of the paper’s editors. Ives’ house was directly across the street from the baseball field, and he would sell rooftop seats for a dime each. Ives was vilified in the local paper: “The antics of this individual…have thoroughly disgusted the people without exception. He is evidently a baseball crank–but of the hog species–without shame or self-respect.”

These interloping spectators robbed the club of vital revenue. So the club installed latticework on top of the fence. Ives responded by outfitting his roof with higher chairs. Infuriated, team manager Henry Marple threatened to turn the stream of a railroad hose on the unauthorized spectators. Finally, the club had to hang canvas over the latticework.Yet Baum came to Ives’ defense. In an article for the newspaper, he argued that “Mr. Ives is not so black as he has been painted” and said that he didn’t deserve insult. Thanks to Baum’s conciliatory efforts, the conflict was resolved by July 25, 1889: Ives agreed to give the club jurisdiction over his property during baseball games.

Short-Lived Success

That inaugural season, the Hub City Nine were the unofficial champions of the Dakotas; they defeated every team in North Dakota and South Dakota. Unfortunately the players still struggled to work as a team, and fans failed to show up in sufficient numbers. Although some of the Ives fans came and bought full-price tickets, the Hub City Nine games didn’t draw enough fans to keep their coffers full. The first season, the club lost about $1,000. Baum was perhaps most disappointed with the season’s outcome; he’d been convinced that Aberdeen could easily support a baseball club. Dejected, he said, “If we are to have a baseball team next year, I am of the opinion that someone else will have to do the work.”

Baum’s Bazaar suffered the same fate. After scarcely a year in business, Baum suffered the “temporary embarrassment” of handing his business over to his creditors. He purchased a newspaper and renamed it the Saturday Pioneer. While the citizens of Aberdeen enjoyed Baum’s writing, the newspaper also folded after only a year. Baum could not handle the stress of being a business owner, and his health suffered. He took a job in Chicago working for a newspaper. The move would set in motion a series of events that resulted in one of the most iconic and beloved stories of the twentieth century, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Related Posts:

L Frank Baum’s Forgotten Foray into Theatre

Rare Books about Baseball Are a Home Run!

The Rare Books of Baseball

Irwin and Erastus Beadle, Innovators in Publishing Popular Literature

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.