Independence Day commemorates the American colonies’ declaring their intention to gain independence from British rule. These items from our inventory illuminate critical moments in history, both before and after the Revolution.

An Account of the European Settlements in America

Published in six parts and two volumes, An Account of the European Settlements in America was written by Edmund Burke and William Burke. The work is most often attributed to Edmund, who was considered a friend of the Americans during the Revolutionary War. That interpretation is an oversimplification, however; though Burke sympathized with the Americans’ dissatisfaction with British rule, he also hoped they’d strive to avoid war. In 1769, Burke published a pamphlet criticizing the British for stirring up conflict with their policies. Five years later, he spoke out against American taxation. Edmund and William were questionably related but referred to one another as “cousins.” The two published their Account in 1757, and Howes lauds it as the “best contemporary account” of the colonies. Details>>

Published in six parts and two volumes, An Account of the European Settlements in America was written by Edmund Burke and William Burke. The work is most often attributed to Edmund, who was considered a friend of the Americans during the Revolutionary War. That interpretation is an oversimplification, however; though Burke sympathized with the Americans’ dissatisfaction with British rule, he also hoped they’d strive to avoid war. In 1769, Burke published a pamphlet criticizing the British for stirring up conflict with their policies. Five years later, he spoke out against American taxation. Edmund and William were questionably related but referred to one another as “cousins.” The two published their Account in 1757, and Howes lauds it as the “best contemporary account” of the colonies. Details>>

The Pennsylvania Evening Post, Vol I No 1 (Tuesday, January 24, 1775)

Published by Benjamin Towne, The Pennsylvania Evening Post initially came out tri-weekly through 1784 with hiatuses during the Revolutionary War. In 1783, Towne modified the paper’s name to The Pennsylvania Evening Post, and Daily Advertiser”–the first daily paper in the United States. On July 6, 1776, the paper was also the first to publish the print the Declaration of Independence. Bingham notes 11 institutional holdings of this first appearance, making it uncommon in the trade. Details>>

Published by Benjamin Towne, The Pennsylvania Evening Post initially came out tri-weekly through 1784 with hiatuses during the Revolutionary War. In 1783, Towne modified the paper’s name to The Pennsylvania Evening Post, and Daily Advertiser”–the first daily paper in the United States. On July 6, 1776, the paper was also the first to publish the print the Declaration of Independence. Bingham notes 11 institutional holdings of this first appearance, making it uncommon in the trade. Details>>

The Naval Atalantis, Parts I & II

Joseph Harris used the pseudonym Nauticus Junior when he published The Naval Atalantis, which makes sense given the critical commentary he offers therein. Harris offers character sketches of  91 British officers, many of whom played a role in the American Revolution. Howes notes than many of the officers “are unmercifully criticised or lampooned by Harris, notably Viscount Wililam Howe, Lord of the Admiralty.” This is a fair assessment; Harris says of Howe “his Lordship’s conduct on the coast of North America, rather served to throw a shade over the laurels he had acquired in his youth.” Harris was reportedly the secretary to Admiral Milbanke, whom Harris features in Part I. Harris’ tone is often quite caustic toward his fellow soldiers. No copies of this edition have been at auction for over thirty years, making it relatively rare in the trade. Details>>

91 British officers, many of whom played a role in the American Revolution. Howes notes than many of the officers “are unmercifully criticised or lampooned by Harris, notably Viscount Wililam Howe, Lord of the Admiralty.” This is a fair assessment; Harris says of Howe “his Lordship’s conduct on the coast of North America, rather served to throw a shade over the laurels he had acquired in his youth.” Harris was reportedly the secretary to Admiral Milbanke, whom Harris features in Part I. Harris’ tone is often quite caustic toward his fellow soldiers. No copies of this edition have been at auction for over thirty years, making it relatively rare in the trade. Details>>

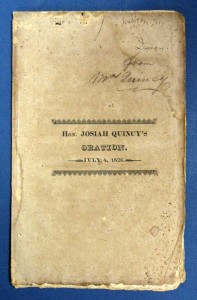

Independence Day Orations of Josiah Quincy III

Josiah Quincy was a soldier in the Revolutionary War, and his namesake would earn the nickname “the Patriot” as principal spokesman for the Sons of Liberty. Thus Josiah Quincy III inherited a legacy of patriotism. He served as a member of the US House of Representatives and as Mayor of Boston before becoming president of Harvard University. Quincy III delivered multiple Independence Day orations to the city of Boston, including one on July 4, 1789 and another on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1826. Details>>

Josiah Quincy was a soldier in the Revolutionary War, and his namesake would earn the nickname “the Patriot” as principal spokesman for the Sons of Liberty. Thus Josiah Quincy III inherited a legacy of patriotism. He served as a member of the US House of Representatives and as Mayor of Boston before becoming president of Harvard University. Quincy III delivered multiple Independence Day orations to the city of Boston, including one on July 4, 1789 and another on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1826. Details>>

Monody on Major Andre

Anna Seward was a prominent woman of letters in her day, having, for example, the admiration of Wordsworth and Scott, and whose disapproval of Dr. Johnson is as well chronicled as her support of young writers of the era is, perhaps, under appreciated. This title, her second published, by the ‘Swan of Lichfield’ [as this poet is known] is a tribute to the suitor of her friend, Honoria Sneyd (stepmother to Maria Edgeworth); the suitor had been executed, as a courier of information from Benedict Arnold to General Clinton, during the Revolutionary War by the Americans. The work’s publication reportedly “brought her an apology from General Washington.” Details>>

Anna Seward was a prominent woman of letters in her day, having, for example, the admiration of Wordsworth and Scott, and whose disapproval of Dr. Johnson is as well chronicled as her support of young writers of the era is, perhaps, under appreciated. This title, her second published, by the ‘Swan of Lichfield’ [as this poet is known] is a tribute to the suitor of her friend, Honoria Sneyd (stepmother to Maria Edgeworth); the suitor had been executed, as a courier of information from Benedict Arnold to General Clinton, during the Revolutionary War by the Americans. The work’s publication reportedly “brought her an apology from General Washington.” Details>>

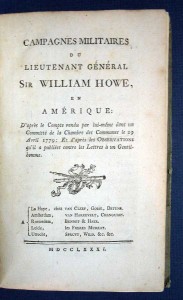

Campagnes Militaires de Lieutenant General Sir William Howe en Amerique

William Howe was the British Commanding General during the Revolutionary War, and here he offers his account. It’s an interesting and scarce edition, with no copies at auction in the last 25 years; OCLC lists only three institutions with this edition. It has a preface not present in the English edition: “‘Twenty times,” exclaims the translator (in this preface dated Amst. 25 Nov. 1780), “have the English encouraged the idea and flattered themselves with it of putting a speedy termination to the war, yet after six years they are no farther advanced in the conquest or reconciliation than they were on the first day.’ [Sabin]. Details>>

William Howe was the British Commanding General during the Revolutionary War, and here he offers his account. It’s an interesting and scarce edition, with no copies at auction in the last 25 years; OCLC lists only three institutions with this edition. It has a preface not present in the English edition: “‘Twenty times,” exclaims the translator (in this preface dated Amst. 25 Nov. 1780), “have the English encouraged the idea and flattered themselves with it of putting a speedy termination to the war, yet after six years they are no farther advanced in the conquest or reconciliation than they were on the first day.’ [Sabin]. Details>>

The Adventures of Christopher Hawkins

During the American Revolution, prisoners of war were treated and managed very differently than they are today; in the eighteenth century, each army was expected to provide supplies and provisions for their own POW’s. Meanwhile, King George III had declared all American soldiers to be traitors, which negated their status as POW’s. Initially, captured American soldiers were simply hanged for treason. However, once the Continental Army caught a large number of British soldiers at the Battle of Saratoga, this practice seemed risky; the British feared reciprocal treatment for their own soldiers. The British resorted to holding their prisoners in dilapidated war ships and prisons. Conditions were deplorable, and many POW’s died as a result. One soldier, Christopher Hawkins was captured and imprisoned on the HMS Jersey off the shore of New York. Hawkins managed to escape, and the details of his captivity were published much later, in a privately printed account. Details>>

During the American Revolution, prisoners of war were treated and managed very differently than they are today; in the eighteenth century, each army was expected to provide supplies and provisions for their own POW’s. Meanwhile, King George III had declared all American soldiers to be traitors, which negated their status as POW’s. Initially, captured American soldiers were simply hanged for treason. However, once the Continental Army caught a large number of British soldiers at the Battle of Saratoga, this practice seemed risky; the British feared reciprocal treatment for their own soldiers. The British resorted to holding their prisoners in dilapidated war ships and prisons. Conditions were deplorable, and many POW’s died as a result. One soldier, Christopher Hawkins was captured and imprisoned on the HMS Jersey off the shore of New York. Hawkins managed to escape, and the details of his captivity were published much later, in a privately printed account. Details>>