Alexandre Dumas – a bibliophile household name around the world, created some of the most memorable stories of love, adventure, history, revenge and politics in the 19th century. On this, what would be his 217th birthday, we would like to pay homage to this wonderful French author and the adventurous worlds he created for his audiences.

Alexandre Dumas was born on July 24th, 1802 the third child of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, a French nobleman of mixed race (his mother having been a slave in Saint-Domingue, now Haiti) and an innkeeper’s daughter. Dumas (Sr., for all intents and purposes) brought his son to France. The young Dumas was given a thorough education and began writing at a young age and publishing articles for magazines and writing stage plays.

When he was 27 years old, Alexandre Dumas saw his first play produced, entitled Henry III and His Courts, which met with acclaim from the very start. A scant year later his second play, Christine, met with just as much success – and Dumas turned his head to writing full time. After enjoying the success of writing several hit plays, Dumas began to try his hand at writing novels. His first novel, published as a serial (as novels often were at the time) was based on one of his earlier, popular plays! Dumas didn’t stop with a work on his Le Capitaine Paul, however… oh, no. Dumas proved to be a very versatile writer indeed, as in the first years of his writing he wrote both an 8-volume compilation (with friends) on Celebrated Crime in European history and a book on a fencing master’s take on the Decemberist Revolt in Russia. It was almost as if Dumas was testing out the waters in his writing, trying different kinds on for size – except that this behavior lasted his entire writing career! Dumas wrote in a variety of styles and genres, most all of which met with success.

Some of his best known and best loved works include The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Muskateers… both of which happen to have been published in the same year. As if we needed more evidence of this accomplished authors’ capabilities, here are some fast facts about Dumas that you may not have known before:

- Dumas is one of the most read of French authors in history.

- Dumas actually at one point built a large chateau outside Paris, that he named the Chateau de Monte-Cristo, right upon its final serial publication in 1846. Unfortunately due to Dumas’ constant money troubles (he spent more than he made on women, entertainment and pleasure) he was made to sell the chateau a mere two years later.

- He once shot down a racist with class, intelligence and total general badass-ery: “My father was a mulatto, my grandfather was a Negro, and my great-grandfather a monkey. You see, Sir, my family starts where yours ends.” Burn baby burn!

- Dumas wrote over 100,000 pages in all, and more have been found and attributed to him even after his death.

- As Napolean Bonaparte disapproved of the author, Dumas fled France for Belgium in 1851 to escape him (and his debts… a happy coincidence).

- He is accounted for having over 40 mistresses, and fathered at least 4 children between them all. (We had to add in some gossipy news, and ask that we are forgiven for our interest in it all!)

One thing is for sure – Dumas was a man dedicated to two things in life… his writing and pleasure. He lived for the pleasure of writing and the pleasures of life that his popular writing afforded him. On this July 24th, let us all strive to be more like Dumas! Enjoy your day, live to enjoy your day… and have a drink to celebrate this magnificent author’s birthday. Cheers!

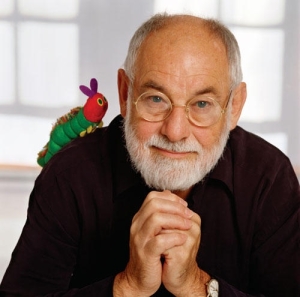

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at  It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.

It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.

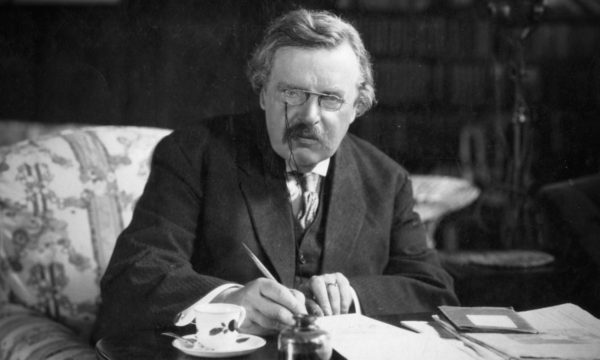

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born on May 29th, 1874, in Kensington, London. His childhood is not elaborately researched, but we do know that he was born to a family of Unitarians, and as a young man was interested in the occult and regularly played (or practiced) with a Quija board with his younger brother (and only sibling) Cecil. He was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, but instead of continuing on to a university as you might have expected, Chesterton attended the Slade School of Art in London – in hopes of eventually becoming an illustrator. Though at Slade Chesterton took lessons in both art and literature, Chesterton left without a degree in either!

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born on May 29th, 1874, in Kensington, London. His childhood is not elaborately researched, but we do know that he was born to a family of Unitarians, and as a young man was interested in the occult and regularly played (or practiced) with a Quija board with his younger brother (and only sibling) Cecil. He was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, but instead of continuing on to a university as you might have expected, Chesterton attended the Slade School of Art in London – in hopes of eventually becoming an illustrator. Though at Slade Chesterton took lessons in both art and literature, Chesterton left without a degree in either! When Chesterton was 27 years old, he married Frances Alice Blogg – an author herself, who would prove to be a major influence on Chesterton’s writing and religious life throughout the years. As www.chesterton.org mentions, Frances was in charge of all aspects of Chesterton’s life – kept his schedule for him, kept house, and kept him in check. According to the site, Chesterton often “had no idea where or when his next appointment was. He did much of his writing in train stations, since he usually missed the train he was supposed to catch. In one famous anecdote, he wired his wife, saying, ‘Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?’” To which Mrs. Chesterton would almost inevitably respond with “Home.” The Chesterton’s were perhaps the epitome of the phrase “Behind every great man is an even greater woman.”

When Chesterton was 27 years old, he married Frances Alice Blogg – an author herself, who would prove to be a major influence on Chesterton’s writing and religious life throughout the years. As www.chesterton.org mentions, Frances was in charge of all aspects of Chesterton’s life – kept his schedule for him, kept house, and kept him in check. According to the site, Chesterton often “had no idea where or when his next appointment was. He did much of his writing in train stations, since he usually missed the train he was supposed to catch. In one famous anecdote, he wired his wife, saying, ‘Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?’” To which Mrs. Chesterton would almost inevitably respond with “Home.” The Chesterton’s were perhaps the epitome of the phrase “Behind every great man is an even greater woman.”

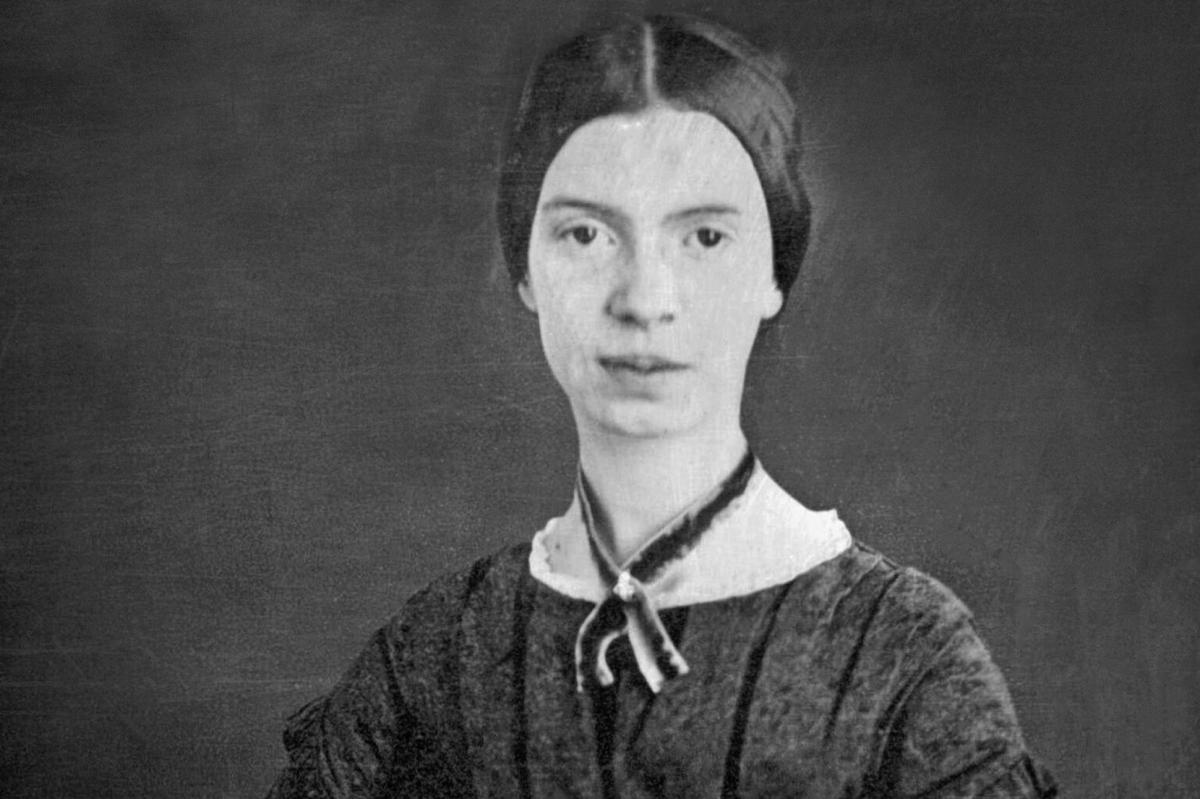

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of. Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

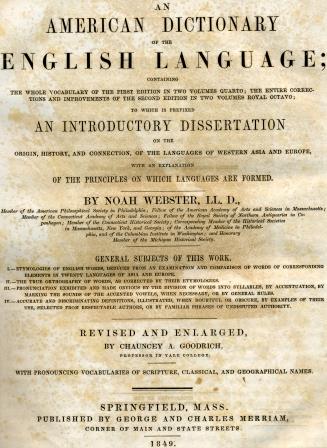

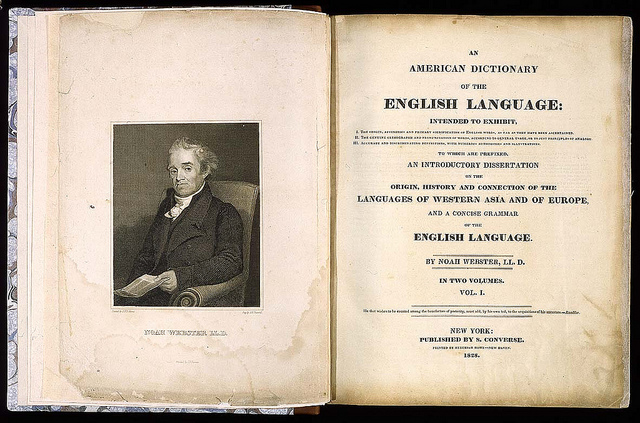

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

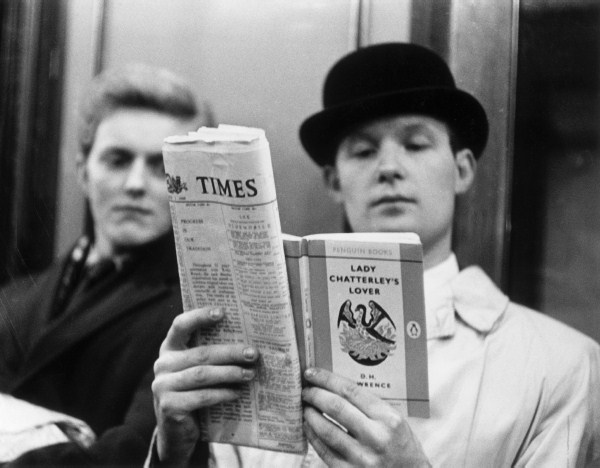

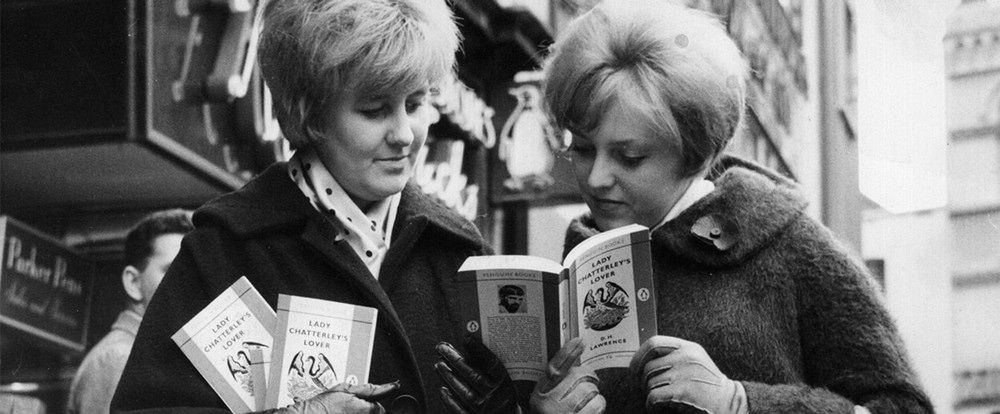

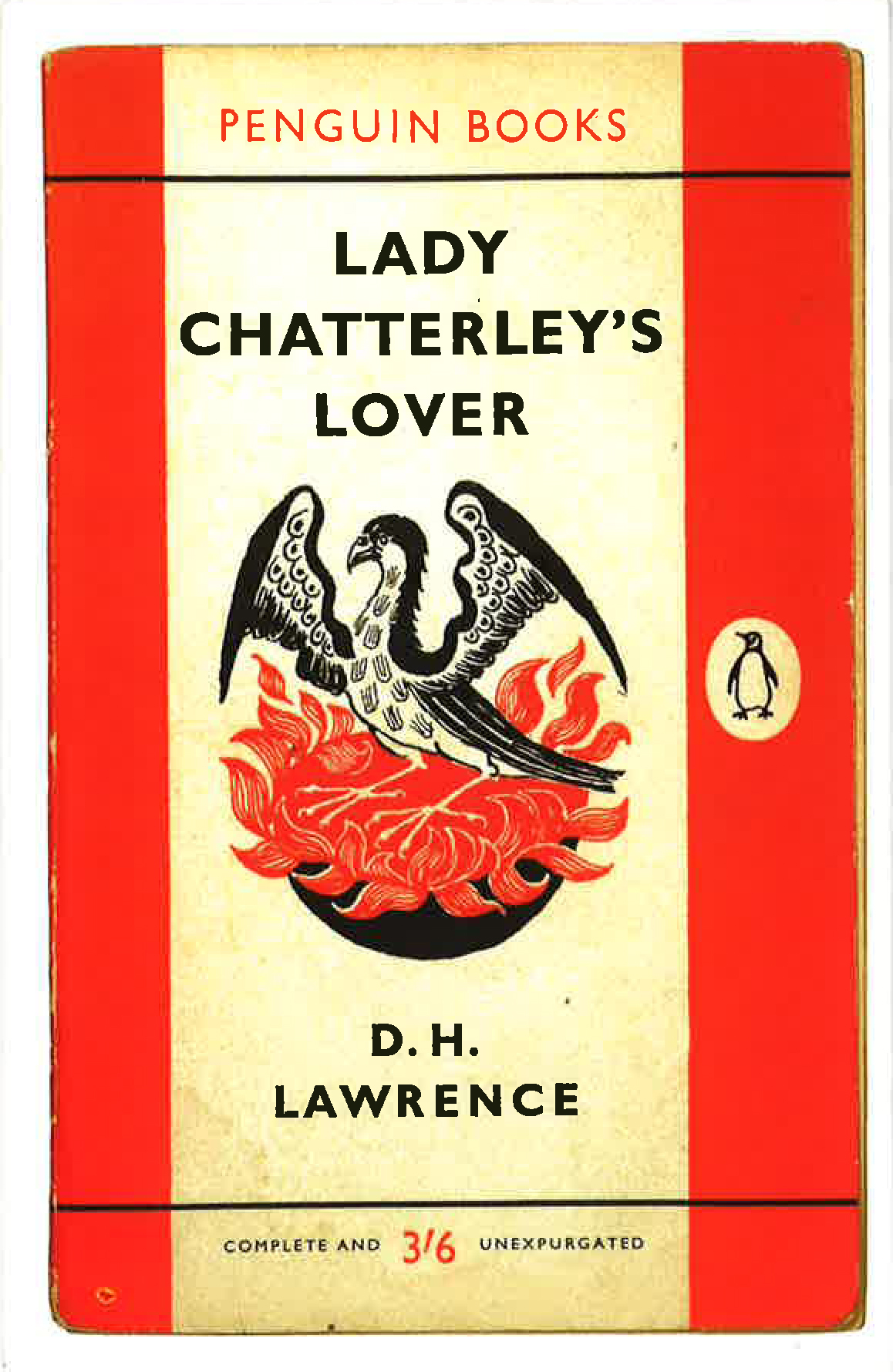

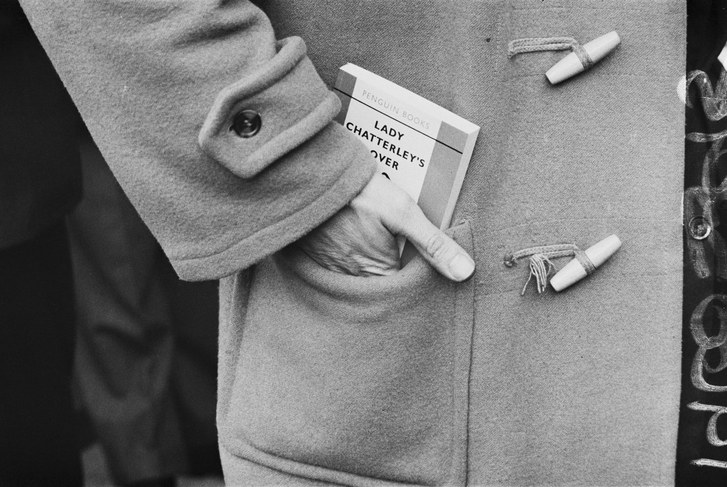

The defense was aided in part due to the previous year’s 1959 Obscene Publications Act, which Parliament passed saying that in order for censorship to take place, the work in question would need to be considered as a whole – without singular focus on the dirtier bits. The prosecution did not fare well anyway, as, despite a conservative following not wishing to see the book in print and in the hands of anyone, lawyer Mervyn Griffith-Jones called no witnesses to support his argument (as no one agreed to stand for the prosecution) and merely suggested that the book had no literary merit. The defense, led by Gerald Gardiner (who would a mere four years later become Labour Lord Chancellor), had rather a different angle. He stated that the book did have merit, that Lawrence wasn’t simply writing smut, but attacking the “impersonality of the industrial age and loss of personal relationships… he was extolling the life-giving importance of romantic and sexual intimacy” (The Telegraph). Gardiner called 35 witnesses to his side – big wigs in academia and literary worlds. He even had a Bishop – the Bishop of Woolwich, who wrote that, though Lawrence was not a Christian himself, he was “portraying the act of sex as something valuable and sacred – as an act of communion” – he went so far as to say that Christians could easily read this title.

The defense was aided in part due to the previous year’s 1959 Obscene Publications Act, which Parliament passed saying that in order for censorship to take place, the work in question would need to be considered as a whole – without singular focus on the dirtier bits. The prosecution did not fare well anyway, as, despite a conservative following not wishing to see the book in print and in the hands of anyone, lawyer Mervyn Griffith-Jones called no witnesses to support his argument (as no one agreed to stand for the prosecution) and merely suggested that the book had no literary merit. The defense, led by Gerald Gardiner (who would a mere four years later become Labour Lord Chancellor), had rather a different angle. He stated that the book did have merit, that Lawrence wasn’t simply writing smut, but attacking the “impersonality of the industrial age and loss of personal relationships… he was extolling the life-giving importance of romantic and sexual intimacy” (The Telegraph). Gardiner called 35 witnesses to his side – big wigs in academia and literary worlds. He even had a Bishop – the Bishop of Woolwich, who wrote that, though Lawrence was not a Christian himself, he was “portraying the act of sex as something valuable and sacred – as an act of communion” – he went so far as to say that Christians could easily read this title.

4. We think this quote by Vidal needs no explanation (but everyone please remember that this is Vidal’s quote – not necessarily ours): “There is only one party in the United States, the Property Party … and it has two right wings: Republican and Democrat. Republicans are a bit stupider, more rigid, more doctrinaire in their laissez-faire capitalism than the Democrats, who are cuter, prettier, a bit more corrupt – until recently … and more willing than the Republicans to make small adjustments when the poor, the black, the anti-imperialists get out of hand. But, essentially, there is no difference between the two parties.” Ouch!

4. We think this quote by Vidal needs no explanation (but everyone please remember that this is Vidal’s quote – not necessarily ours): “There is only one party in the United States, the Property Party … and it has two right wings: Republican and Democrat. Republicans are a bit stupider, more rigid, more doctrinaire in their laissez-faire capitalism than the Democrats, who are cuter, prettier, a bit more corrupt – until recently … and more willing than the Republicans to make small adjustments when the poor, the black, the anti-imperialists get out of hand. But, essentially, there is no difference between the two parties.” Ouch!