Many men born in the states during and after the revolution were more die-hard Americans than any of the foam fingered MAGA supporters we see today. After all, they were the children of the revolution… either they or their fathers fought hard to ensure our country’s freedom, and they weren’t about to let us forget it. They used whatever skills they had – political? They wrote the Constitution. Physical? They fought in battles. Academic? They wrote Declaration of Independence, or essays on our rights… or a dictionary of the American English language. Today we’d like to discuss one such man – who wrote the first American dictionary. With its over 70,000 entries it was more conclusive than ever before, and included words specific to America.

We may be young… but we invented the word “hickory.” So there.

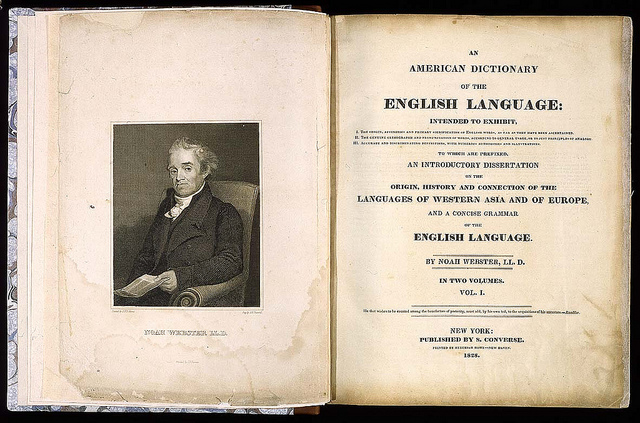

Noah Webster was born in 1758 in West Hartford, Connecticut. His father, though a farmer by trade, was at the same time a deacon of their local church, captain of the town’s small militia, and a founder of the local book society (which later because the local public library). Though his father did not have extensive educational knowledge, Webster (Sr.) did have a thirst for learning, comprehension, and understanding. His wife began teaching her son to read and write at a young age, and after attending small, dilapidated schools in the region and using a private tutor, and after his father mortgaged their family farm to pay the tuition fees, Noah Webster was able to enroll at Yale College when he was 16 years old… during the height of revolutionary unrest, and he continued studying during the Revolutionary War.

After graduating from Yale, Webster began teaching, then quit to study law, and finally passed the bar exam in 1781. One can imagine it was trying times to be finding a job and earning a living, what with the Revolutionary War still raging on. He began a small private school in Western Connecticut that he closed shortly thereafter, then he wrote essays for local papers praising the Revolution, and then he opened yet another school, but this time for the wealthy of New York. It was at this establishment that he began work on his first “speller” – a grammar and reader for use in elementary classes. The revenue from this first venture is what enabled Webster to spend the next years working on his infamous dictionary.

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

Over these years, Webster focused on one specific way he personally could help his beloved new country. He wanted to promote an American approach to educating our children, and wanted to “rescue our native tongue from the ‘clamour of pedantry’ that surrounded English grammar and pronunciation.” He said that the English language had suffered the British aristocracy’s approach to spelling and pronunciation – an outdated and elite way of speaking and teaching. He eventually began work on his lifetime’s achievement… The Webster Dictionary.

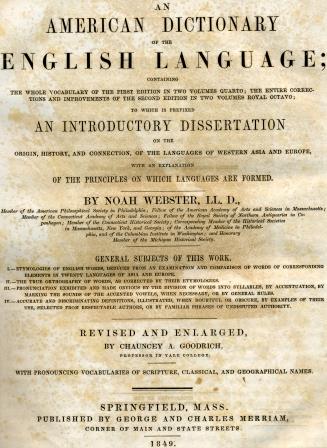

In 1806 Webster published the first attempt – A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language – the first actual American dictionary of its kind, but knew immediately it was not enough. He continued working on his opus. He learned somewhere between 26-28 languages in evaluate their importances and meanings, and connected with people around the east coast of the new America in order to gather words and meanings from around the “country.” At the tender age of 70, Webster published his dictionary in 1828. Though at first it only sold 2,500 copies, and Webster ended up re-financing his home to pay for a second edition… we all know the eternal significance his dictionary would play on us all… as the Webster (now Webster-Merriam, after rights were granted to the publishing brothers in 1843) Dictionary is still used in schools and households across the United States today.

This week we celebrate its publication (as the copyright was registered by Webster on April 14th, 1828) and the lasting impact it has had on America… just as Noah Webster wished it to.

Credit: University of Washington libraries.