AA Milne with son, Christopher Robin (1925). Christopher later resented having been the inspiration for the eponymous character in Milne’s classic ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ tales.

Alan Alexander Milne came to regret that his beloved Winnie-the-Pooh series overshadowed his other works. Yet some of his most interesting pieces were never even attributed to him. An outspoken pacifist during World War I, Milne secretly served in Britain’s M17b unit, writing pro-war propaganda. But by World War II, Milne’s views on war had changed, creating a rift between him and beloved author PG Wodehouse.

Born on January 18, 1882 in Scotland, Milne spent his childhood in London. His tutor, the young HG Wells, was, according to Milne “a great writer and a great friend.” Milne went on to Westminster School and Trinity College. He edited Granta for a year, and his preliminary literary efforts appeared in Punch magazine. Just after his 24th birthday, Milne became the assistant editor of Punch. He held the post until World War I began.

An Outspoken Pacifist

At the start of World War I, Milne enlisted in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He served as a signalling officer and did a brief stint in Paris before being discharged due to trench fever. Milne never even fired at an enemy; indeed, his most notable service remained a complete secret until recently. Thanks to a set of long-lost documents secretly saved from destruction, we now know that Milne was part of the classified M17b unit.

Established in 1916, the unit included twenty of Britain’s top writers of the time. Their mission: to produce propaganda that would sustain support for the war at a time when the number of casualties was rapidly rising and anti-war movements were sprouting all over Europe. The unit not only wrote accounts of Victoria’s Cross winners and other war heroes, but they also focused on the atrocities perpetrated by the Germans.

Captain James Lloyd

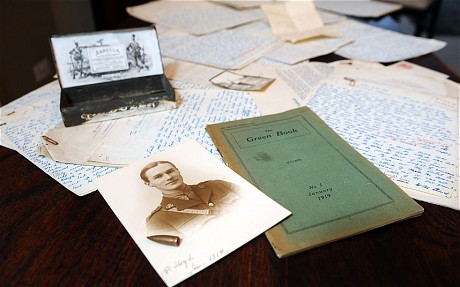

Alongside Milne were Cecil Street, the author of the Dr. Priestley novels; “the Navvy Poet” Patrick MacGill; Roger Pocock, the world-traveling author; JP Morton, who earned his fame with The Bystander; and Captain James Lloyd, who was recruited to join the unit after being wounded in combat. It was Captain Lloyd who defied orders and took about 150 of the unit’s classified documents home. They were discovered last year by his great nephew Jeremy Alder, who discovered them just before they were going to be thrown away.

Among the documents recovered was The Green Book, which is marked “for private circulation.” There were likely no more than twenty copies ever published. The pamphlet included contributions from the unit’s authors and poked fun at the task of creating government propaganda. Milne’s own contributions illustrate how onerous he found the task. In “Captain William Shakespeare, of a Cyclist Battalion,” Milne writes:

In M17b

who loves to lie with me

About atrocities

And Hun corpse factories

Come hither, come hither, come hither,

Here shall we see

No enemy

But sit all day and blather

In “Some Early Propagandists,” also compiled in The Green Book, Milne writes about Paul von Hindenburg, the German Field Marshal. Hindenburg would go on to become Germany’s President and to appoint Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany.

Captain Lloyd’s cache of M17b documents, which included ‘The Green Book’

After the war ended, Milne went on to great success, largely due to his Winnie-the-Pooh series. He also published Peace with Honour: an Enquiry Into the War Convention, which was an overtly pacifist work. Milne said that he wrote it because “I want everybody to think (as I do) that war is poison, and not (as so many think) an overstrong, extremely unpleasant medicine.”

World War II Brings a Change of Heart

But by World War II, Milne had changed his mind. In 1940, he even went so far as to publish War with Honour, in which he states, “War is something of a man’s own fostering; and if all mankind renounces it, then it is no longer there.” Soon Milne inflicted his newfound hawkishness on PG Wodehouse, an author with whom he’d previously enjoyed mutual admiration.

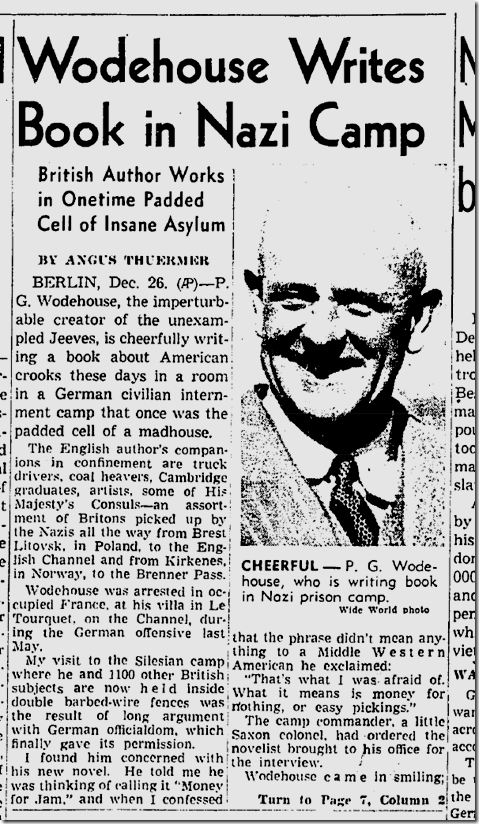

Milne had long enjoyed Wodehouse’s writing–he even read it to his own son, Christopher Robin, instead of his own stories. But as Wodehouse’s career took off in the 1930’s, Milne’s was burning less brightly. When Wodehouse began doing radio broadcasts for the Nazis, Milne was first in line to accuse the imprisoned author of treason, possibly out of jealousy. Wodehouse and his wife were in France when the Nazis invaded in 1940. They were taken to an internment camp. A few Nazis had known Wodehouse thanks to his Hollywood projects, and they asked Wodehouse to do radio broadcasts detailing his experiences at the camp.

Wodehouse likely had little say in the matter; after all, did one really argue with the Nazis? Wodehouse complied, though his broadcasts were probably far from what the Nazis had in mind; with characteristic wit, Wodehouse made sport of the Nazis. After reading the transcripts, one British Air Marshal marveled that the Nazis had permitted Wodehouse to complete five broadcasts; “Why the Germans let him say all this I cannot think,” he observed, “They have either got more sense of humor than I credit them with,or it just slipped past the censor. Wodehouse has probably been shot by now.”

When Wodehouse’s countrymen found out about the broadcasts, they were furious. Even though they’d never head them, they were confident that Wodehouse had agreed to the task in exchange for favored treatment. People vociferously excoriated Wodehouse, and Milne was chief among his detractors. The furor soon grew into hysteria. Milne dismissed the possibility that Wodehouse had simply been naive, calling the author irresponsible. He said that Wodehouse “has encouraged in himself a natural lack of interest in ‘politics’–‘politics’ being all the things grown-ups talk about at dinner while one is hiding under the table. Things, for instance like the last war, which found and kept him in America, and post-war taxes, which chased him back and forth across the Atlantic.”

Wodehouse was released in 1941. He was cleared of any wrongdoing but was unable to overcome the stigma that had tarnished his reputation. Wodehouse would exact some revenge in “The Mating Season” and “Rodney Has a Relapse,” where he mocks the literary insignificance of Milne’s work and points out that Milne had exploited his own young son to attain literary fame. Wodehouse also once admitted, “Nobody could be more anxious than myself…that Alan Alexander Milne would trip over a loose bootlace and break his bloody neck.”

Milne and Wodehouse never spoke again, and all evidence suggests that Milne held on to the grudge till the end of his life. Wodehouse, on the other hand, was able to let go. When he learned that Milne was ailing, he expressed regret and noted that Milne was “about my favorite author.” Regardless of how they felt about each other, both AA Milne and PG Wodehouse remain beloved figures in modern British literature.

Related Posts:

Edith Cavell: Nurse, Historian, and Traitor?

The Man Behind the Beloved ‘Freddy’ Series

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.