The term “propaganda” has come to have a negative connotation in much of the English-speaking world. But in some places, the word is neutral or even positive. Why this difference? The reasons can be traced through the word’s etymology and the way that this strategy of communication has evolved over the centuries.

Roots in the Catholic Church

The use of propaganda began much earlier than most people would imagine. The Behistun Inscription, from around 515 BCE, details Darius I’s ascent to the Persian throne and is considered an early example of propaganda. And ancient Greek commander Themistocles used propaganda to delay the action of–and defeat–his enemy, Xerxes, in 480 BCE. Meanwhile, Alexander put his image on coins, monuments, and statues as a form of propaganda. Roman emperor Julius Caesar was considered quite adept at propaganda, as were many prominent Roman writers like Livy.

But it was the Catholic Church that both formalized the use of propaganda and gave us the word itself. Pope Urban II used propaganda to generate support for the Crusades. Later, propaganda would become a powerful tool for both Catholics and Protestants during the Reformation. Thanks to the printing press, propaganda could be disseminated to a much wider audience.

The 300th anniversary of the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide was commemorated on Italian currency.

In 1622, Pope Gregory XV established the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith) for the purpose of promoting the faith in non-Catholic countries. The group’s name was often informally shortened to “propaganda,” and the name stuck. As literacy rates grew in subsequent centuries, propaganda became a more and more useful tool around the world. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were both considered adept propagandists during the American Revolution.

Literacy Propagates…Propaganda

By the nineteenth century, propaganda had finally emerged in the form we think of it today. Because most people were literate and had more than passing interest in government affairs, politicians found it necessary to sway public opinion. They turned to (sometimes unscrupulous) propaganda to get the job done.

A notorious propaganda campaign of the 1800’s was that of the Indian Rebellion in 1851. Indian sepoys rebelled against the British East India Company’s rule. The British grossly exaggerated–and sometimes completely fabricated–tales of Indian men raping English women and girls. The stories were intended to illustrate the savagery of the Indian people and reinforce the notion of “the white man’s burden” to rule, induce order, and instill culture in less civilized peoples who could not be trusted to rule themselves.

Abolitionists in both the US and Britain also aggressively used propaganda to support their cause. Certainly the conditions of slavery were heinous, but they often exaggerated or eroticized transgressions, making them more lurid. These efforts were complemented by freed slaves who traveled to speak at public events. The speakers generally made arguments against slavery based on moral, economic, and political grounds. The combination of emotional and rational arguments proved an excellent combination for winning supporters to the abolitionist cause.

Meanwhile another powerful form of communication was emerging in the nineteenth century: the political cartoon. Though illustrated propaganda had been used in the past, the form of the political cartoon was significantly refined during the second half of the century. Thomas Nast is considered one of the forerunners of this format.

Global Conflict Gives Propaganda New Power

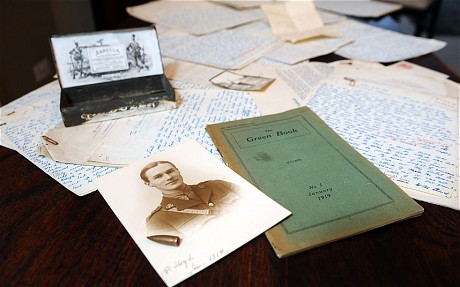

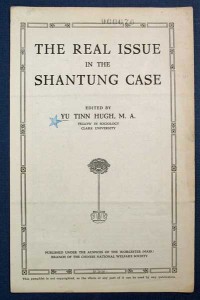

This 1919 propaganda publication assails the Shantung settlement incorporated in the Treaty of Versailles.

World War I saw the first large-scale, formalized propaganda production. Emperor Wilhelm of Germany immediately established an unofficial propaganda machine with the creation of the Central Office for Foreign Services. One of the office’s primary duties was to distribute propaganda to neutral countries.

After the war broke out, however, Britain immediately severed the undersea cables that connected Germany to the rest of the world; Germany was limited to using a powerful wireless transmitter to broadcast pro-German news to other nations. The country also set up mobile cinemas, which would be sent to the troops at the front lines. The films emphasized the power, history, and inevitable victory of the German Volk.

Meanwhile, the British propaganda machine was regarded as an “impressive exercise in improvisation.” It was rapidly brought under government control as the War Propaganda Bureau. Journalist Charles Masterson led the organization. On September 2, 1914, Masterson invited Britain’s leading writers to a meeting to discuss potential messaging. Attendees included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, GK Chesterton, Ford Madox Ford, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, and HG Wells. Winnie-the-Pooh author AA Milne would later be recruited to covertly write propaganda.

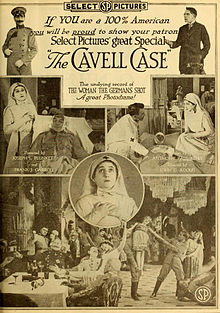

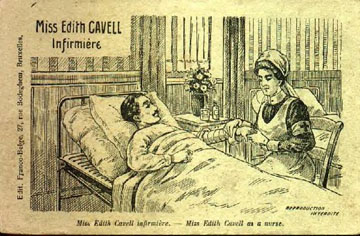

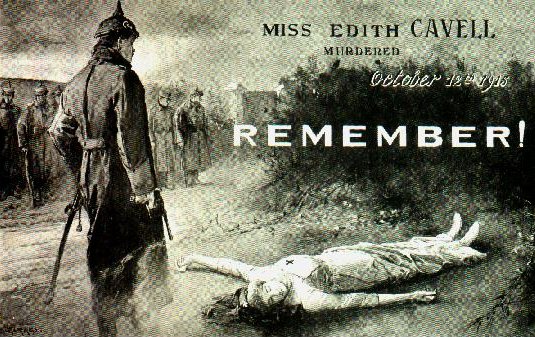

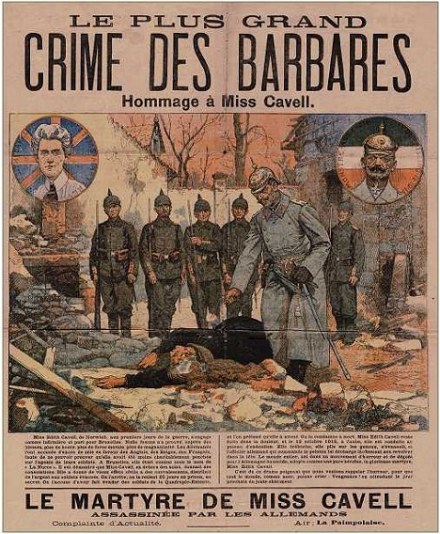

The propaganda of World War I was frequently based on complete exaggeration or misinformation. For example, nurse Edith Cavell was executed for treason after using her position as a nurse to help soldiers escape from behind German lines. The episode was used to exaggerate German atrocities, and it was even made into a movie. (Read more here.) Indeed, by the end of the war, people had begun to tire of propaganda.

Yet the British propaganda machine was quite effective. It is frequently credited with persuading the United States to enter the war in the first place. Adolf Hitler actually studied British propaganda after the war, declaring it both brilliant and effective. He would later enlist Joseph Goebbels to help with propaganda during World War II, and the two proved an indomitable team. They masterminded multiple campaigns to justify eugenics programs, extermination of target populations, and other atrocities. The Allies countered with propaganda that vilified the Germans.

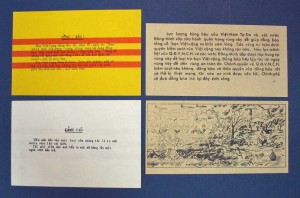

This collection of South Vietnamese GVN propaganda were probably air drop leaflets. Though usually dropped in mass quantities, few survive.

When the true horrors of Nazi Germany came to light, the extreme power of propaganda was terribly apparent. The word “propaganda” soon developed a negative connotation, one that it still carries to this day in the English-speaking world. Airdrop leaflet campaigns during unpopular engagements like the Korean War and Vietnam War often brought the communication even lower.

Now it’s common for a government authority to regulate propaganda, and it may be used for more innocuous purposes like public health and safety campaigns. But in non-democratic countries, propaganda continues to flourish as a means for indoctrinating citizens, and this practice is unlikely to cease in the future.

Related Posts:

Edith Cavell: Nurse, Humanitarian, and Traitor?

AA Milne: Legendary Author and Ambivalent Pacifist

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.