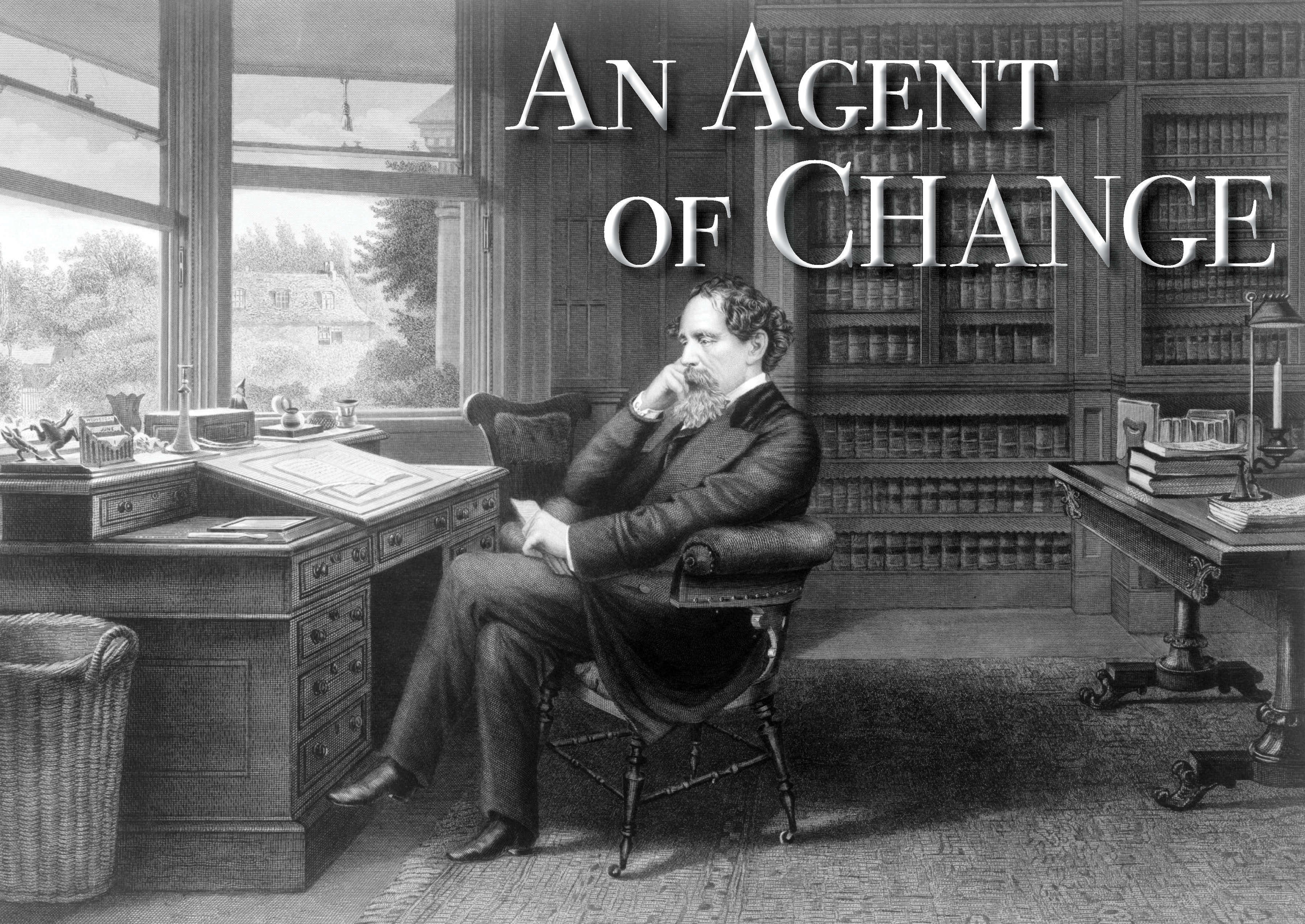

On this auspicious occasion – the 150th Anniversary of Dickens’ death – there is no shortage of notional blog topics. We could discuss the strange diet he had on days when he did his public readings (a raw egg beaten in a glass of sherry was part of it), the curious nicknames he had for his children (“Skittles” was probably a joy – who knows what went wrong with “Lucifer’s Box”), or perhaps the ivory toothpick he once used that sold at auction for $9,000.

Given everything going on in the world at the moment, we decided to give whimsy a pass and focus on a single, defining aspect of Dickens. Relevance.

As an author – arguably the most famous in the world during his lifetime – Dickens was well-known and widely read. But that can be said of many authors in many times. Part of what continues to make Dickens fascinating was how he leveraged both his literary gifts and the attention they commanded. Despite his many faults, Dickens was a force for positive social reform and change. One might even argue that for his time, he was a radical agent for social change. It seems a good time to talk about how one man used his pen to give voice to those without one, to infuse entertainment with informing empathy, and to leverage personal fame to help others less fortunate than himself.

It is impossible to look at Dickens’ interest in the poverty-stricken, down-trodden members of society without a brief introduction to his early life. Charles John Huffam Dickens was born on the 7th of February, 1812 into a modest Portsmouth household that boasted his mother, father, and an older sister. Dickens’ father was a clerk in the Navy Pay Office, and for a time the family enjoyed a modest but happy life – a lifestyle some have referred to as “gentile poverty”. At just three years old, the young Charles and his family relocated to bustling London, where his father was transferred after the end of the Napoleonic War. London proved to be a difficult life for the constantly growing family, and the charismatic John Dickens began to fall into serious debt.

At the age of twelve, young Charles was packed off to Warren’s Blacking – a boot polish manufacturer. For a time, the young boy would work from early morning until late into the night. However, soon after Charles began work his father was arrested and the entire family moved into debtor’s prison. It was only after John Dickens’ mother died, leaving behind a small inheritance for the family to pay their debts and survive on, that they were able to leave Marshalsea Prison. This period would have an immense impact on Charles Dickens’ view of the world and on his writing. He would never forget the way being so unspeakably poor had opened his eyes to the world. In short, Charles Dickens lived a truly “Dickensian” childhood, surviving in extremely poor social conditions. Though the term may have been coined based on the living conditions of characters in his books, we can see that Charles did not invent the lifestyle – nor did he have to imagine it.

Skipping ahead, after Dickens achieved success with his writing (after all, the point of this blog is to bring attention to his efforts in social reform, not to his literary successes), we see Dickens becoming an advocate for many of the less fortunate. The Victorian period in England saw many advances in industry and technology – creating a rising tide of urbanization. Industrialism was at its height, but the division of wealth between the wealthy aristocracy and the poor was beyond considerable. The working class was on the rise, true, but the poverty stricken lower class life experience would be considered untenable today in the western world. The extortion of child labor, abuse of labor practices in general, homelessness and/or a lack of sanitation in housing, prostitution and general squalor were only some of the problems facing the lower classes in Victorian England. Though many upper class citizens remained ignorant of these many difficult subjects, Dickens chose to write about them. And because he did so with compelling craft and deeply engaging stories, he was able to command attention that no conventional soapbox could rival.

Combining his skills of humor and satire with a keen observation of society at large, Dickens brought attention to the many injustices against the downtrodden in Victorian England. He did not just write about them fictionally, however. When he could, he donated his own money. When he couldn’t, or wanted to do more than simply contribute cash, he pushed the wealthy to donate their time and resources. Most often, however, he used his fame and celebrity, but most of all talent to aid charitable institutions. Dickens was no stranger to giving speeches, performing readings, or writing articles for causes he believed in. Over his lifetime, he in some way supported at least 43 charitable institutions. Some of these included the Poor Man’s Guardian Society, the Birmingham and Midland Institute, the Metropolitan Sanitary Association, The Orphan Working School, the Royal Hospital for the Incurables, and the Hospital for Sick Children.

One of Dickens’ most well-known and sustained philanthropic efforts was his work with the notable (and extremely wealthy) Miss Angela Burdett Coutts. The two met and became close friends in 1839, and were in contact for many years before Dickens approached her with an idea – a home for homeless and “fallen” women. Dickens wanted to get these women off the streets – many of whom had turned to a life of prostitution to survive – and teach them skills to make a living or marry and have a family. Dickens oversaw every part of this project – from finding the home to helping pick out candidates. Urania Cottage, as it was called, provided safety, a home and support to homeless and fallen girls and turned out dozens of recharged women over a ten year period. Until a rift with Coutts developed in 1859, Dickens worked tirelessly on behalf of his charity for women.

Now, Urania Cottage is just a single example of Dickens’ generosity. He gave to organizations, institutions, and even to families and individuals as often as he could. We have already mentioned how he was able to use his talents in both writing and readings to bring attention and awareness to difficult subjects. He also put forth tireless efforts into the Field Lane Ragged School – a school for destitute children, run by Evangelicals. Though Dickens had reservations about the religious leader of the school, he enthusiastically gave his time, money and resources into creating a safe space for these children to learn “religious instruction, elementary education, training in trades and food” (J. Don Vann) through volunteers in evening classes. He believed in free education, and thought that through equal (and therefore free) tuition throughout England, crime and destitution would decrease. He was not wrong.

The take away from these stories is this… here was arguably the most famous writer in the world since Shakespeare, scouting homes and schools himself for the poor and the homeless, using his time and influence to gain money and support, and keeping involved in the running of the charities even after they were set up. Dickens was not simply an armchair philanthropist. He put himself in the thick of it and wanted desperately to make a difference. Though scholars have occasionally thought it impossible to legitimately trace any direct reform legislation to Dickens’ work, there can be no doubt that he opened up discussions and used intelligence and humor to bring attention to social abuses and system deficiencies. Charles Dickens showed us one path that could be used to direct change – not the only path.

Though as Dickens scholars and purveyors of his work we adore the satire and intelligence of his literature, we realize this does not absolve him of any wrong doings in his personal life and sphere. We are not, under any circumstances, promoting Dickens as the perfect humanitarian. As we stated earlier, he certainly had his faults. But what we can learn from Mr. Dickens, especially in a time such as this – a time of radical positive change, but also of confusion and pain – is that nothing at all will happen if we don’t first put forth the effort.

As actor and Dickens scholar Simon Callow once said: “The reason I love him so deeply is that, having experienced the lower depths, he never ceased, till the day he died, to commit himself, both in his work and in his life, to trying to right the wrongs inflicted by society, above all, perhaps by giving the dispossessed a voice… From the moment he started to write, he spoke for the people, and the people loved him for it, as do I.”

Further Dickens reading & information:

Dickens in a Crisis 150th Anniversary YouTube video

Bleecker Street Media

Denton Dickens Fellowship

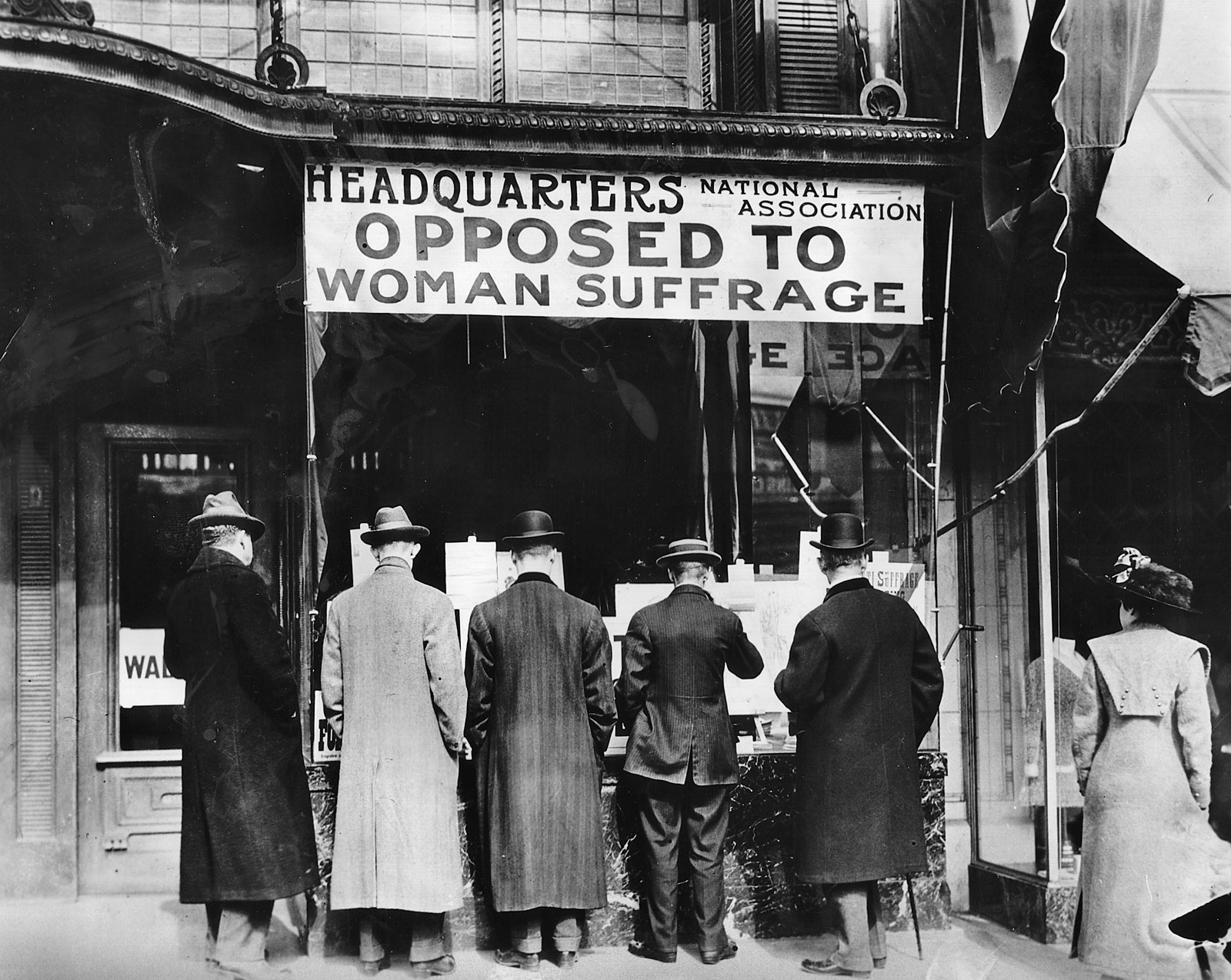

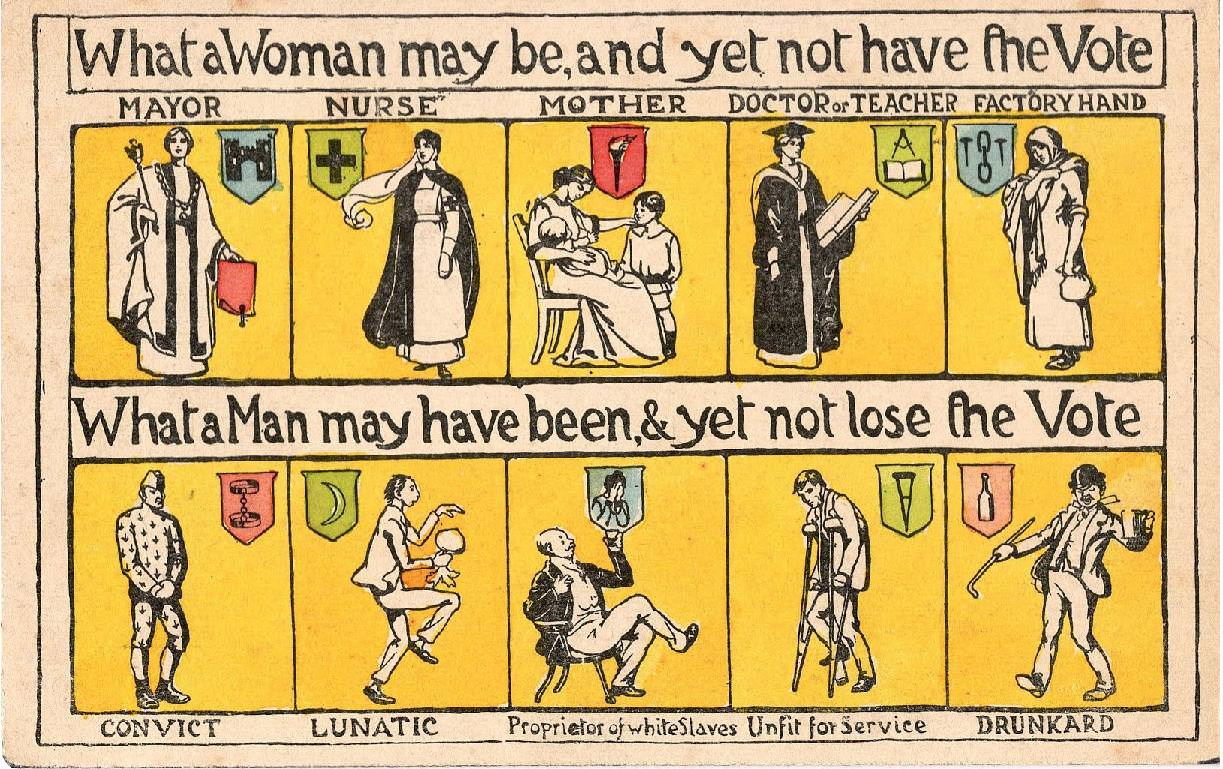

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.

The opposition of female public speaking wasn’t simply a hurdle. Much of the opposition was so strong that it led to violence. Many female conventions and rallies were disrupted with extreme forcefulness and cruelty, inciting suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to state this: “No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized.” Her statement cemented the fact that it was not so much the idea of women voting that bothered their contemporaries, but rather it was women breaking out of the cages they had for so long been held and standing up for themselves publicly that was the problem.  In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (two of the main “heavy hitters” in the suffrage movement) joined forces to create the National Woman Suffrage Association, and began the fight for a “universal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution” (History.com). It was Stanton’s belief early on that the only way to change the way women were treated was through government political reform. While some believed that though women deserved rights, support, protection (from domestic abuse) and equal pay – they did not necessarily require the right to vote, Stanton believed the right to vote was integral to all the other matters listed. And she was not wrong. The same year, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). These two leagues were enmeshed in a bitter feud that would last decades, their participants disagreeing on the Fifteenth Amendment – allowing African American men the right to vote. Some, like Stanton and Anthony, rejected the Amendment, believing that woman’s suffrage was more important, and mistakenly believing that African American men opposed women’s suffrage and would fight against their cause. Stone and other members of AERA, on the other hand, supported their previously oppressed fellow citizens and supported their victories, in hopes they would help support the women’s movement in return. This is not to say that racial bias did not exist in both organizations, as it most definitely did, despite both groups being strongly associated with the abolitionist movement. Their rivalry would last until 1890.

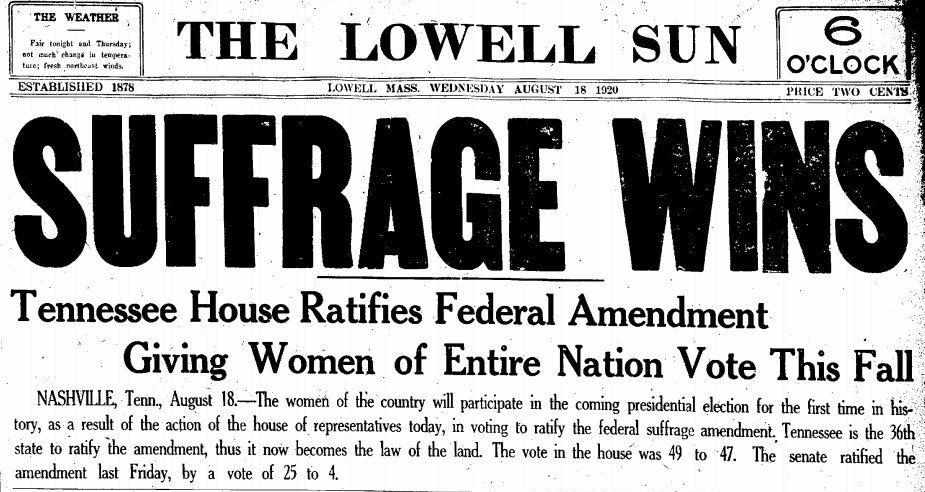

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

In 1910, some of the Western states slowly began extending the vote to their female citizens. State by state, women were gaining rights (though there was still a significant ways to go). States in the South and the Northeast resisted. WWI once again slowed the momentum of the party, but women’s work in the war effort helped to engender support for their intelligence and abilities in the long run. Their aid proved their patriotism and that they were as deserving of rights as men were. A parade for women’s rights in 1917 in New York City consisted of hundreds of women, carrying placards with over 1 million female signatures on them… a far cry from where they started out, with less than 1% of the population’s support.

Carson eventually got a temporary position with the United States Bureau of Fisheries, a job which she had been on the fence about but was persuaded to take by one of her college mentors. She spent her time there writing radio copy for “weekly educational broadcasts entitled Romance Under the Waters.” With 52 programs in the series, Carson had her work cut out for her. The episodes focused on aquatic life and was meant to prompt interest in biology of fish and the work the Bureau did. During this time, Carson’s interest in marine life grew, and soon she was submitting articles on aquatic life in the Chesapeake Bay to local newspapers and magazines. She impressed her superiors with her dedication and knowledge to the point where they offered her the first full-time position that became available, as a junior aquatic biologist.

Carson eventually got a temporary position with the United States Bureau of Fisheries, a job which she had been on the fence about but was persuaded to take by one of her college mentors. She spent her time there writing radio copy for “weekly educational broadcasts entitled Romance Under the Waters.” With 52 programs in the series, Carson had her work cut out for her. The episodes focused on aquatic life and was meant to prompt interest in biology of fish and the work the Bureau did. During this time, Carson’s interest in marine life grew, and soon she was submitting articles on aquatic life in the Chesapeake Bay to local newspapers and magazines. She impressed her superiors with her dedication and knowledge to the point where they offered her the first full-time position that became available, as a junior aquatic biologist. Over ten years at the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (as it was by then called) were good to Carson – she had become the chief editor of publications. Years after the first interest shown by publishers, Carson was once again on the book-publishing path. This time, Oxford University Press expressed interest in a life history of the ocean. Her completed work would eventually become The Sea Around Us. Several chapters were published serially in the Yale Review, Science Digest and The New Yorker, until it was finally published as a book in July 1951. It was an immediate bestseller, remaining at the top of the New York Times Bestseller List for 86 weeks straight. This success gave Carson the ability to give up her job at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and focus on her writing full time.

Over ten years at the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (as it was by then called) were good to Carson – she had become the chief editor of publications. Years after the first interest shown by publishers, Carson was once again on the book-publishing path. This time, Oxford University Press expressed interest in a life history of the ocean. Her completed work would eventually become The Sea Around Us. Several chapters were published serially in the Yale Review, Science Digest and The New Yorker, until it was finally published as a book in July 1951. It was an immediate bestseller, remaining at the top of the New York Times Bestseller List for 86 weeks straight. This success gave Carson the ability to give up her job at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and focus on her writing full time. Her books on the ocean life continuing to be popular, best selling works across the country, Carson began focusing much of her research on pesticide use in the United States, something she had been interested in for over a decade, but finally had the time and space to work on it. By 1957, the USDA was proposing widespread pesticide spraying – to eradicate fire ants and other pests. Carson was suspicious of some of the toxic chemicals they were proposing using, including DDT – a now known carcinogen. She worried what kind of effect the runoff from this activity would have on coastal life, and for good reason. Carson would spend the rest of her life focusing her efforts on conservation, with a great emphasis on “the dangers of pesticide overuse.” In September 1962, Houghton Mifflin published what would become Carson’s best-known book, Silent Spring. This work described in detail the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment, and is credited worldwide with helping begin the modern environmental movement. “Carson was not the first, or the only person to raise concerns about DDT, but her combination of “scientific knowledge and poetic writing” reached a broad audience and helped to focus opposition to DDT use.” She also poetically noted the dangers of human nature on the environment, a verifiable fact . Carson was, truly, ahead of her time. Unfortunately taken from us much too soon (passing away at the age of only 56 after a battle with breast cancer), Rachel Carson will live on with every moment that we choose to put the good of the planet above ease of our lives.

Her books on the ocean life continuing to be popular, best selling works across the country, Carson began focusing much of her research on pesticide use in the United States, something she had been interested in for over a decade, but finally had the time and space to work on it. By 1957, the USDA was proposing widespread pesticide spraying – to eradicate fire ants and other pests. Carson was suspicious of some of the toxic chemicals they were proposing using, including DDT – a now known carcinogen. She worried what kind of effect the runoff from this activity would have on coastal life, and for good reason. Carson would spend the rest of her life focusing her efforts on conservation, with a great emphasis on “the dangers of pesticide overuse.” In September 1962, Houghton Mifflin published what would become Carson’s best-known book, Silent Spring. This work described in detail the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment, and is credited worldwide with helping begin the modern environmental movement. “Carson was not the first, or the only person to raise concerns about DDT, but her combination of “scientific knowledge and poetic writing” reached a broad audience and helped to focus opposition to DDT use.” She also poetically noted the dangers of human nature on the environment, a verifiable fact . Carson was, truly, ahead of her time. Unfortunately taken from us much too soon (passing away at the age of only 56 after a battle with breast cancer), Rachel Carson will live on with every moment that we choose to put the good of the planet above ease of our lives.