“I’ll be a poet, a writer, a dramatist. Somehow or other I’l be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be infamous.” –Oscar Wilde

Born on October 16, 1854 in Dublin, Ireland, Oscar Wilde is perhaps remembered more for his sparkling wit, larger-than-life personality, and historic trial than for his literary achievements. But the author made his mark on the literary world not only through his prolific career as a journalist, novelist, and dramatist, but also through his sometimes bizarre relationships with other literary figures. These interactions make collecting Wilde an even more engaging pursuit.

Born on October 16, 1854 in Dublin, Ireland, Oscar Wilde is perhaps remembered more for his sparkling wit, larger-than-life personality, and historic trial than for his literary achievements. But the author made his mark on the literary world not only through his prolific career as a journalist, novelist, and dramatist, but also through his sometimes bizarre relationships with other literary figures. These interactions make collecting Wilde an even more engaging pursuit.

Love Lost between Wilde and Bram Stoker

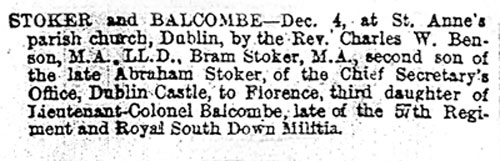

Wilde’s mother, Lady Jane, was a formidable author in her own right. She often kept literary company, and her circle of friends soon came to include Bram Stoker. Stoker soon met Florence Balcombe, a legendary beauty who had previously been involved with Wilde. Accounts of Balcombe’s relationship with Wilde vary; he claimed the two had been engaged. At any rate, Wilde was less than pleased when he learned that Stoker had proposed to Balcombe. He wrote to Balcombe, stating that he would never return to Ireland again. Wilde mostly kept to his word, returning to Ireland only for brief visits.

But Stoker and Wilde’s relationship stretched beyond this inopportune love triangle. The two had gone to school together; Stoker even recommended Wilde for membership into the university’s Philosophical Society. And after Stoker and Balcombe had been married and Wilde had had sufficient time to lick his wounds, Stoker reinitiated the relationship. After Wilde was convicted of sodomy, Stoker even visited him. Yet Stoker also fastidiously removed all mention of Wilde from his published and unpublished texts, and it’s only recently that critics have begun to see Wilde’s influence in Stoker’s great novel Dracula.

Wilde Rejects Dickens’ Legacy…Or Does He?

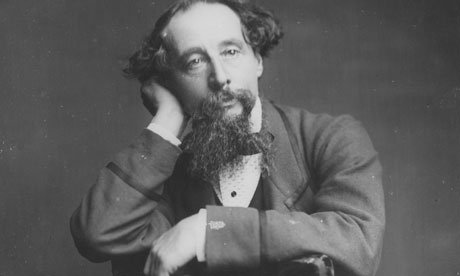

Wilde heaped praise upon Matthew Arnold, Robert Browning, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. He even called Aurora Leigh “the greatest work in our literature.” But he was less than complimentary when it came to the great Charles Dickens; Wilde is famous for saying of Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop, “One would have to have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell and not to dissolve into tears…of laughter.” Wilde found Dickens overly sentimental and wished to separate himself from this aspect of Dickens’ Victorian England. Yet he never fully succeeded in escaping Dickens’ shadow (indeed, few authors of the century did).

Wilde heaped praise upon Matthew Arnold, Robert Browning, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. He even called Aurora Leigh “the greatest work in our literature.” But he was less than complimentary when it came to the great Charles Dickens; Wilde is famous for saying of Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop, “One would have to have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell and not to dissolve into tears…of laughter.” Wilde found Dickens overly sentimental and wished to separate himself from this aspect of Dickens’ Victorian England. Yet he never fully succeeded in escaping Dickens’ shadow (indeed, few authors of the century did).

Critics have pointed to similarities in the ways that Wilde and Dickens portray London, and Wilde even makes allusions to Dickens’ works–most notably Little Dorritt. Little Dorritt’s Mrs. General repeats the phrase “Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism” to her young charges, and the phrase “prunes and prism” soon became closely associated with her character. Is it any coincidence, then, that Wilde chooses the name “Ms. Prism” for the proper governess in The Importance of Being Earnest? Even though Wilde didn’t subscribe to Dickens’ sentimental style, it’s likely that he had great respect for Dickens, as Wilde himself aspired to the same international acclaim that the Inimitable One had achieved.

An Outlandish Claim Spurred by Public Rivalry

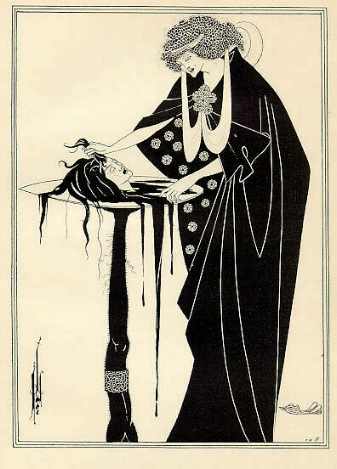

In April 1893, an up and coming artist was moved by the French publication of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. He drew Salome with St. John’s head, and the illustration became one of several that would accompany Joseph Pennell’s article on him in the first number of The Savoy. The artist, Aubrey Beardsley, contacted Wilde about illustrating the translation of Salome. Wilde responded in kindness, sending Beardsley an inscribed edition that read “For Aubrey: for the only artist who knows what the dance of seven veils is, and can see that invisible dance. Oscar” It wasn’t outright rejection, but it wasn’t an enthusiastic invitation, either.

In April 1893, an up and coming artist was moved by the French publication of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. He drew Salome with St. John’s head, and the illustration became one of several that would accompany Joseph Pennell’s article on him in the first number of The Savoy. The artist, Aubrey Beardsley, contacted Wilde about illustrating the translation of Salome. Wilde responded in kindness, sending Beardsley an inscribed edition that read “For Aubrey: for the only artist who knows what the dance of seven veils is, and can see that invisible dance. Oscar” It wasn’t outright rejection, but it wasn’t an enthusiastic invitation, either.

Then Beardsley was contracted to illustrate Lord Alfred Douglas‘ English translation of Salome. Wilde initially called Beardsley’s illustrations for the work “too Japanese,” pointing out that the work was more Byzantine. Wilde then took his criticism a step further, saying that Beardsley’s art resembled “naughty scribbles a precocious boy makes on the margins of his copybook.” The rivalry exploded; Beardsley published caricatures of Wilde, and Wilde made the preposterous claim that he had “invented Aubrey Beardsley.” In reality, Wilde had simply worried all along that Beardsley’s brilliance would overshadow his own.

Mutual Admiration from a Distance

In November 1879, George Bernard Shaw met Oscar Wilde at Lady Jane’s London home. The two had trouble interacting, though Wilde clearly had good intentions toward Shaw. A few years later, on July 6, 1888, Wilde attended a meeting of the Fabian Society, likely at Shaw’s invitation. Artist Walter Crane spoke on “The Prospects of Art under Socialism,” which soon moved Wilde to write The Soul of Man under Socialism. Meanwhile over the years Shaw and Wilde maintained a pleasant relationship, albeit from a distance. They frequently exchanged books and letters and openly complimented each other’s works.

Shaw frequently defended Wilde against his critics, and he again rallied to Wilde’s defense when he was arrested for sodomy. Shaw was adamant that “never was there a man less an outlaw” than Wilde. Shaw and other writers put together a petition for Wilde’s early release, but it found surprisingly little support and was eventually dropped. As public opinion turned against Wilde and eventually forgot him entirely, Shaw still insisted on reminding people of Wilde’s greatness. He regularly mentioned him in drama reviews and remained fascinated with Wilde’s work for the rest of his life. When Frank Harris undertook his (somewhat controversial) biography of Wilde, Shaw edited it with the assistance of Lord Douglas.

Collecting Oscar Wilde

For collectors, Oscar Wilde is the ideal case study in how a single-author collection can–and should–come to include materials by a variety of other authors. A comprehensive Oscar Wilde collection would encompass the works of Wilde, not only his major literary pieces, but also the articles he penned as a journalist and critic. And a truly comprehensive collection would have a second layer: other authors’ reactions to and interactions with Wilde. For example, Shaw’s reviews mentioning Wilde are scarce because they were printed in periodicals on cheap paper, making them a challenging item for collectors to acquire. And Aubrey Beardsley’s caricatures of Wilde are sought after by both Beardsley and Wilde collectors alike, making them a desirable addition to an Oscar Wilde collection.

Oscar Wilde certainly left his mark on the world as an author and public figure. He will undoubtedly remain a popular figure among rare book collectors for generations to come.