The history of nursing is filled with illustrious figures like Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton. But there are plenty of women whose contributions to this noble vocation are overlooked.

Elizabeth Fry

A Quaker and Christian philanthropist, Elizabeth Fry came to be known as the “angel of prisons.” At eighteen years old, Fry was moved by the sermons of American Quaker William Savey. She immediately took an interest in caring for the poor, sick, and incarcerated. Her efforts led her to Newgate Prison, where she was horrified to find the women’s prison crowded with both women and their children. She soon became an outspoken advocate for improving prison conditions, even spending the night in prisons occasionally herself and inviting members of nobility to do the same.

A Quaker and Christian philanthropist, Elizabeth Fry came to be known as the “angel of prisons.” At eighteen years old, Fry was moved by the sermons of American Quaker William Savey. She immediately took an interest in caring for the poor, sick, and incarcerated. Her efforts led her to Newgate Prison, where she was horrified to find the women’s prison crowded with both women and their children. She soon became an outspoken advocate for improving prison conditions, even spending the night in prisons occasionally herself and inviting members of nobility to do the same.

In 1840, Fry established a training school for nurses. Florence Nightingale later took a group of Fry’s nurses to assist wounded soldiers in the Crimean War, and her experience working with them inspired her to start a similar program. By this time, Fry was quite well known throughout England; even Queen Victoria was an admirer of her work. The monarch granted Fry a few audiences and donated to her causes.

Anna Morris Holstein

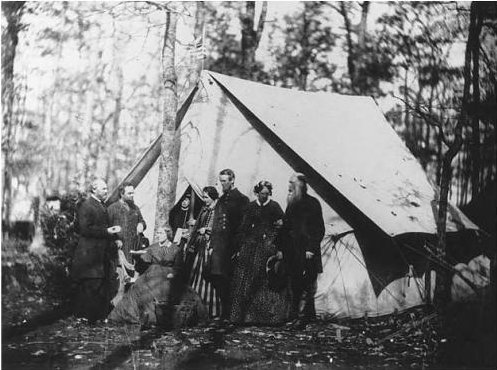

Anna Morris Holstein may have been the last person you’d expect to see traveling with soldiers. She and her husband, William H. Holstein, were quite wealthy. But they still had a strong sense of duty. William had served in the Pennsylvania militia during Lee’s 1862 invasion. And when the couple witnessed the carnage at Antietam, they felt called to serve. Anna noted, “we have no right to the comforts of our home, while so many of the noblest of our land renounce theirs.”

The couple enlisted with the US Sanitation Commission. Anna struggled with the grisly realities of war and later admitted that she was of little use till she could gain control of her composure and stop crying. Even after she was more experienced, Anna would succumb to emotion when she received “earnest thanks” from a soldier. After the war, publisher JB Lippincott capitalized on the hunger for war stories, first with Hospital Sketches, then less successfully with Notes of Hospital Life (1864). Anna’s Three Years in Field Hospitals of the Army of the Potomac fit the bill to continue the trend.

The couple enlisted with the US Sanitation Commission. Anna struggled with the grisly realities of war and later admitted that she was of little use till she could gain control of her composure and stop crying. Even after she was more experienced, Anna would succumb to emotion when she received “earnest thanks” from a soldier. After the war, publisher JB Lippincott capitalized on the hunger for war stories, first with Hospital Sketches, then less successfully with Notes of Hospital Life (1864). Anna’s Three Years in Field Hospitals of the Army of the Potomac fit the bill to continue the trend.

Alice Fisher

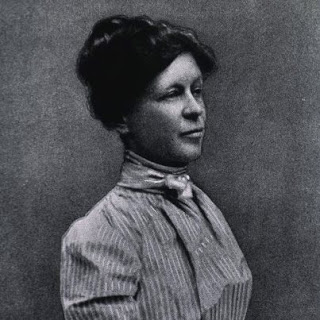

Alice Fisher didn’t immediately embark on a career in nursing. She started out as an author. Fisher penned Too Bright to Last in 1873, and the three-volume His Queen in 1875. But her father, an astronomer and priest, took ill and soon passed away, leaving Fisher to make her own way. She decided to pursue nursing, and went to school at the Nightingale Training School and Home for Nurses, where her mentor was none other than the founder herself. The two corresponded, but no letters are extant.

Alice Fisher didn’t immediately embark on a career in nursing. She started out as an author. Fisher penned Too Bright to Last in 1873, and the three-volume His Queen in 1875. But her father, an astronomer and priest, took ill and soon passed away, leaving Fisher to make her own way. She decided to pursue nursing, and went to school at the Nightingale Training School and Home for Nurses, where her mentor was none other than the founder herself. The two corresponded, but no letters are extant.

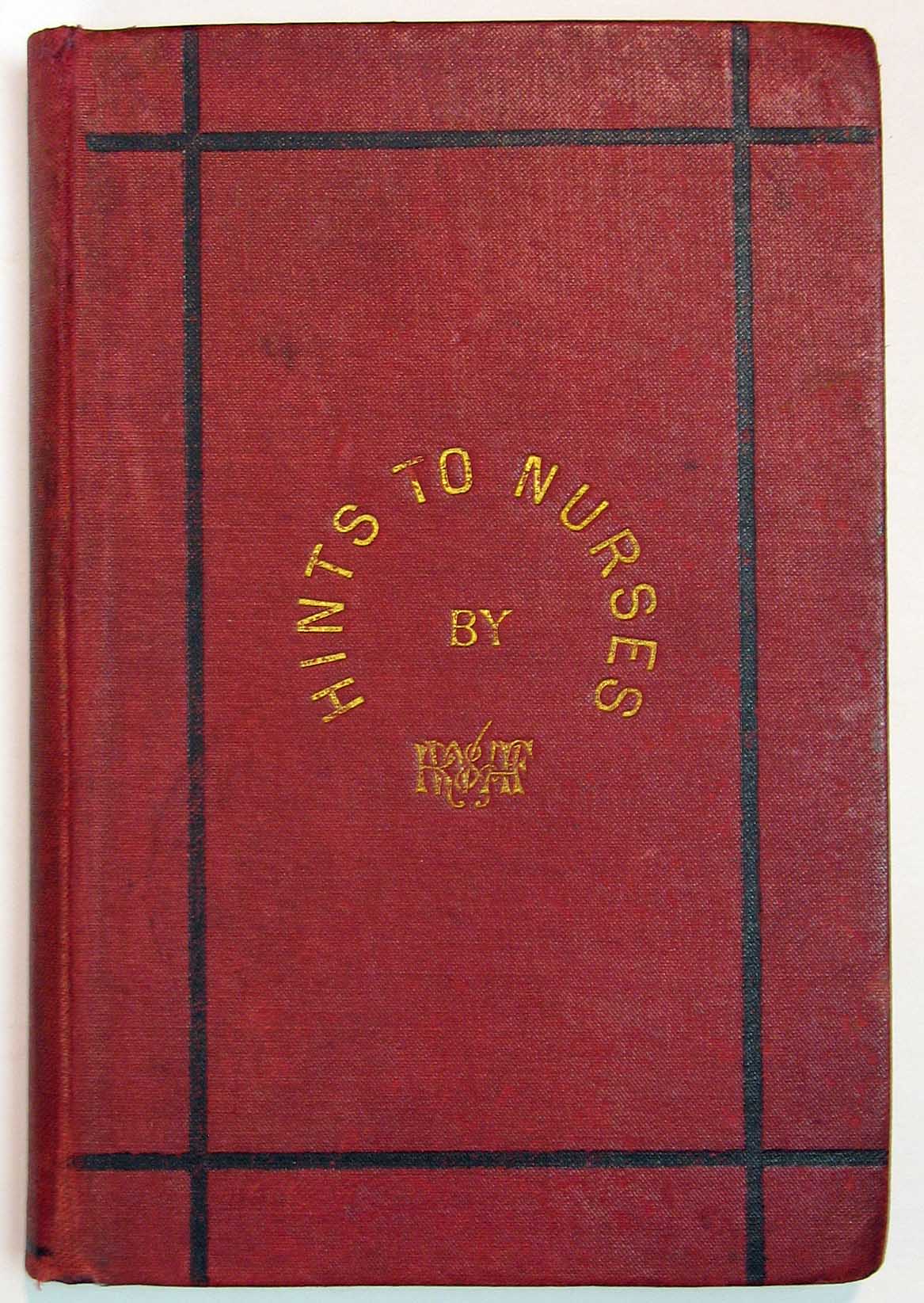

Fisher came to the US in 1884 as the superintendent of Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH), then more commonly known as Buckley Hospital. Fisher made sweeping changes to the hospital. Her approach was a sterling example of the benefits of standardized training for nurses. Along with fellow Nightingale nurse Rachel Williams, Fisher edited Hints for Hospital Nurses (1877).

Fisher came to the US in 1884 as the superintendent of Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH), then more commonly known as Buckley Hospital. Fisher made sweeping changes to the hospital. Her approach was a sterling example of the benefits of standardized training for nurses. Along with fellow Nightingale nurse Rachel Williams, Fisher edited Hints for Hospital Nurses (1877).

Lavinia Dock

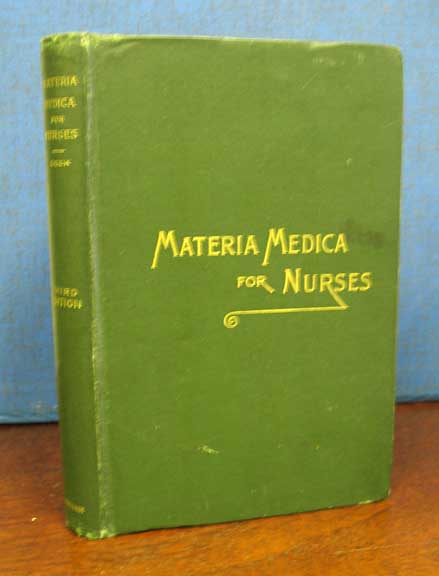

Lavinia Dock graduated from the Bellevue Hospital School of Nursing in 1886. Two years later, she was in Florida during a yellow fever outbreak. Dock served alongside Jane Delano, who went on to found the American Red Cross Nursing Service. Dock was a contributing editor to American Journal of Nursing and authored a number of books on the subject, including a four-volume history of nursing and a nurse’s drug manual that was the standard reference for years. Dock served as the assistant superintendent of Johns Hopkins School of Nursing under Isabel Hampton Robb. Dock, Robb, and Mary Adelaide Nutting would go onto found to organization that evolved into the National League for Nursing.

Lavinia Dock graduated from the Bellevue Hospital School of Nursing in 1886. Two years later, she was in Florida during a yellow fever outbreak. Dock served alongside Jane Delano, who went on to found the American Red Cross Nursing Service. Dock was a contributing editor to American Journal of Nursing and authored a number of books on the subject, including a four-volume history of nursing and a nurse’s drug manual that was the standard reference for years. Dock served as the assistant superintendent of Johns Hopkins School of Nursing under Isabel Hampton Robb. Dock, Robb, and Mary Adelaide Nutting would go onto found to organization that evolved into the National League for Nursing.

After Dock retired from nursing, she turned her attention more fully to the issue of women’s rights. She became active in the National Woman’s Party, leading numerous protests–including a picket of the White House. Dock was actually arrested on three separate occasions for militant protesting. But her efforts paid off, and she was instrumental in the passage of the 19th Amendment. This wasn’t Dock’s only political concern; she also lobbied for legislation that would allow nurses to control their own profession, rather than being overseen by doctors.

After Dock retired from nursing, she turned her attention more fully to the issue of women’s rights. She became active in the National Woman’s Party, leading numerous protests–including a picket of the White House. Dock was actually arrested on three separate occasions for militant protesting. But her efforts paid off, and she was instrumental in the passage of the 19th Amendment. This wasn’t Dock’s only political concern; she also lobbied for legislation that would allow nurses to control their own profession, rather than being overseen by doctors.

This month we’re pleased to offer works by these four women, along with a number of other select acquisitions on nursing. We invite you to peruse the entire list. Should you have a question about an item, please don’t hesitate to contact us!

Related Posts:

Edith Cavell: Nurse, Historian, and Traitor?

Famous Figures in the History of Nursing (Part One)

Clara Barton: Heroine of Civil War Nursing and Record Keeping

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.