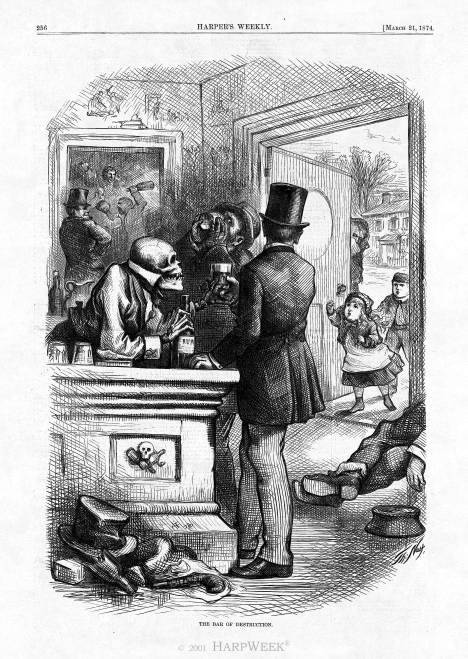

The above cartoon by Thomas Nast appeared in Harper’s Weekly on March 21, 1874. The following page bore another temperance cartoon by Michael Angelo Woolf called “The Social Juggernaut.” The issue also included a story of a temperance demonstration at a New York bar and an illustrated poem called “Like Father, Like Son,” which tells the story of a father and son who both fall into alcoholism. The back page cartoon depicts a bottle of rum in prison for “manslaughter in the greatest degree.”

Interest in temperance and prohibition continued to grow over the next several decades, culminating in the ratification of the 18th Amendment on January 16, 1919. By this time, the temperance movement had been around for over a century. In 1784, Benjamin Rush wrote An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind. His treatise blamed alcohol for a wide range of physical and psychological problems. By 1789, a group of Connecticut farmers formed a temperance association and applied Rush’s work, banning the production of whiskey in their county. By 1800, Virginia also had a temperance association, and New York followed in 1808.

Most activists at this time supported moderation, rather than complete abstinence. But as the movement grew, leaders tried to use their increased audience to promote other issues like attending church on Sundays. That approach backfired. The movement splintered and fell apart completely by 1820. Despite a lack of cohesive support, the idea of temperance had taken hold. Many states, counties, and cities were dry. That didn’t mean that alcohol consumption had waned; in fact, from 1800 to 1830, per capita alcohol consumption reached its highest level in American history. It was three times today’s rate, and most of that consumption was hard liquor drunk undiluted. One historian actually labeled the US at this time the “alcoholic republic.”

To garner support, temperance leaders modeled their rallies after religious revivals. They primarily relied on moral and religious arguments, and some began lobbying for the regulation and/or prohibition of alcohol. In 1826, the American Temperance Society was founded, lending the movement new momentum. By 1838, the organization had over one million members and more than 8,000 local groups. This time, there was a definitive split between moderates (who supported drinking in moderation) and radicals (who believed in complete prohibition of all alcohol).

The radicals were, predictably, much more vocal and soon dominated the movement. By the early 1850’s, thirteen states had banned the manufacture and sale of alcohol. Alcohol consumption had fallen significantly, and more people were opting for beer instead of hard liquor–a preference that some culinary historians attribute in large part to the influx of German immigrants.

But the Civil War derailed the temperance movement completely. Both the North and the South struggled to fund the war, and they turned to distillers and brewers for financial support. Drinking also became a sort of bonding activity for soldiers, who were away from their wives and families. Support for temperance and prohibition dried up.

After the war ended, the nation experienced an explosion in the retail liquor industry. The number of dealers went up 17% between 1864 and 1873…even though the population grew only 2.6%. It wasn’t until the end of the Reconstruction that prohibitionism gained steam again. First, it took root in the South; the ideals of prohibition and protecting the home dovetailed with “traditional Southern values,” such as traditional gender roles and even racial stereotypes.

Soon prohibitionism had entered politics. Most temperance advocates were Republicans, but leaders of both parties tried to distance themselves from the most divisive issues. Ultimately prohibition advocates decided that neither political party adequately represented their interests, and the Prohibition Party was born. The party still exists today and has nominated a presidential candidate for every election since 1872. Though it faded into obscurity with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the Prohibition Party is the oldest third political party in the United States.

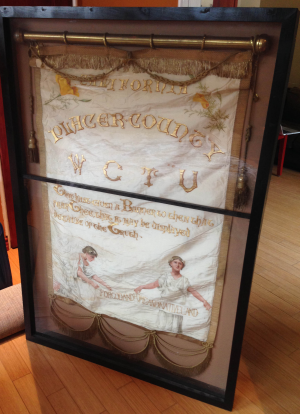

Unfortunately, women were still excluded from politics, so they sought other ways to support the movement. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union all began with Dr. Dio Lewis. A prominent proponent of temperance, Dr. Lewis traveled the country for decades, telling a story about how his mother and other women had inspired local business owners to turn away from alcohol sales with prayer and scripture.

Inspired by Dr. Lewis in December 1873, a group of women banded together to take direct action against saloons and liquor sales in what came to be known as the Women’s Crusade of 1873-1874. At first, women would gather at saloons and drop to their knees-for pray ins. They would sing hymns and demand that the establishment stop serving alcohol. With these grassroots demonstrations, they managed to halt alcohol sales in 250 communities. Then in the summer of 1874 at a pre-organizational meeting in Chautauqua, members decided to hold a national convention in Cleveland, Ohio.

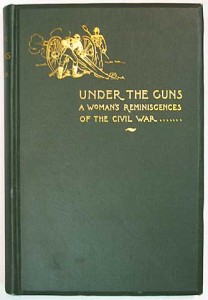

In Cleveland, Annie Wittenmyer was elected the first president of the WCTU. Wittenmyer had been a nurse during the Civil War and would go on to author Under the Guns about her experience. Under her guidance, the WCTU took up temperance as a “protection of the home.” The organization’s watchwords were “Agitate-Educate-Legislate.” Local chapters were called unions, and they were largely autonomous. The WCTU quickly became the largest women’s organization in the country.

In Cleveland, Annie Wittenmyer was elected the first president of the WCTU. Wittenmyer had been a nurse during the Civil War and would go on to author Under the Guns about her experience. Under her guidance, the WCTU took up temperance as a “protection of the home.” The organization’s watchwords were “Agitate-Educate-Legislate.” Local chapters were called unions, and they were largely autonomous. The WCTU quickly became the largest women’s organization in the country.

The WCTU’s protest against alcohol was ultimately much more than that: it was a means of protesting women’s lack of civil rights. At the time, women couldn’t vote. Domestic abuse and rape cases almost never found their way to prosecution. Women had no right to property or custody of their children if they got divorced. And in some states, the age of consent was still as low as seven. Meanwhile, most political meetings were held in saloons, which informally excluded women from participation in politics.

In 1879, Frances Willard became president of the WCTU. Her personal motto was “Do everything,” and she believed that the organization should expand its scope to address a full range of social problems, which were, after all, interconnected. Use of substances like drugs and alcohol was really just a symptom of greater societal ills. By 1894, the WCTU had taken up the cause of women’s suffrage and had become one of the first organizations to keep a professional lobbyist in Washington, DC.

The WCTU undertook a number of initiatives to promote temperance. People often opted to drink beer or liquor because there was no access to clean drinking water. So the WCTU advocated the installation of public drinking fountains. And in cooperation with Mary Hunt, the WCTU established a curriculum for formal temperance instruction in classrooms across the nation. Their goal: “teach that alcohol is a dangerous and seductive poison; that fermentation turns beer and wine and cider from a food into poison; that a little liquor creates by its nature the appetite for more; and that degradation and crime result from alcohol.”

When the 18th Amendment was finally ratified, the WCTU continued to advocate temperance, but shifted its focus to other social issues. The repeal of the amendment sparked another shift in focus. Today, the WCTU addresses the abuse of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco, along with gambling and pornography.

Related Books

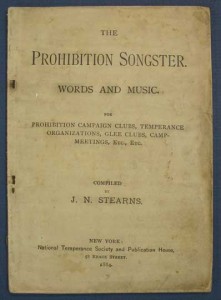

The Prohibition Songster

Compiled by John Newton Stearns, The Prohibition Songster was intended for “Prohibition Campaign Clubs, Temperance Organizations, Glee Clubs, Camp Meetings, Etc, Etc.” It was first published in 1884 by the National Temperance Society and Publication House. Such items were frequently produced for use during political campaigns, and the National Temperance Society says of this particular publication, “This is a new collection of words and music for Temperance Gatherings, with some of the most soul-stirring songs ever published. Music by some of the best composers, and words by our best poets.” One hundred copies could be purchased for $12. OCLC records five institutional copies. Details>>

Compiled by John Newton Stearns, The Prohibition Songster was intended for “Prohibition Campaign Clubs, Temperance Organizations, Glee Clubs, Camp Meetings, Etc, Etc.” It was first published in 1884 by the National Temperance Society and Publication House. Such items were frequently produced for use during political campaigns, and the National Temperance Society says of this particular publication, “This is a new collection of words and music for Temperance Gatherings, with some of the most soul-stirring songs ever published. Music by some of the best composers, and words by our best poets.” One hundred copies could be purchased for $12. OCLC records five institutional copies. Details>>

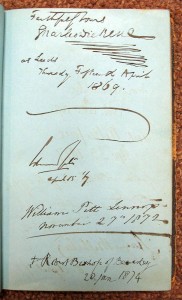

Autograph Album-Leeds Town Hall (1861-1895)

This rare album contains the autographs of visitors to the Leeds Town Hall. The album was owned by a J. (or F.) N. Dickinson who has signed the ffep and added the date Oct 9th 1861. Each of the 59 pages (beginning on the verso of the ffep) contain numerous autographs, primarily of musicians who we assume were performing there on the dates noted. Among the dignitaries to sign the autography book are Charles Dickens, Charles Stratton (aka, Tom Thumb), Scottish explorer John MacGregor (better known as Rob Roy). Lady Isabella Somerset, former president of the British Women’s Temperance Association, also signed. All in all it’s a truly fascinating artifact. Details>>

This rare album contains the autographs of visitors to the Leeds Town Hall. The album was owned by a J. (or F.) N. Dickinson who has signed the ffep and added the date Oct 9th 1861. Each of the 59 pages (beginning on the verso of the ffep) contain numerous autographs, primarily of musicians who we assume were performing there on the dates noted. Among the dignitaries to sign the autography book are Charles Dickens, Charles Stratton (aka, Tom Thumb), Scottish explorer John MacGregor (better known as Rob Roy). Lady Isabella Somerset, former president of the British Women’s Temperance Association, also signed. All in all it’s a truly fascinating artifact. Details>>

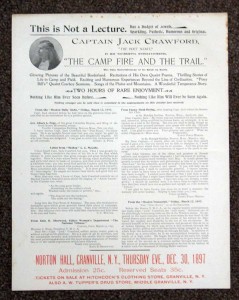

Captain Jack Crawford, “The Poet Scout,” in His Wonderful Entertainments, “The Camp Fire and the Trail”

John Wallace “Jack” Crawford was an American adventurer, educator, and author known as one of the most popular performers in the late nineteenth century. His daring actions to carry the news the 350 miles to Ft. Laramie in six days of General George Crook’s victory in the Battle of Slim Buttes during the Great Sioux War made him instantly famous. After his stints in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and “General Crook’s Horsemeat March,” Crawford served as a special agent for the US Department of Justice, spending four years investigating illegal liquor traffic and fighting alcoholism on Indian reservations. During his work for the US Government, he began his career as an entertainer in 1893 which continued until 1898. He wrote poetry and held “lectures” across the United States where he told of his many adventures in the Wild West, and where he asked his audiences to be careful and foreswear liquor in order to lead a more fulfilled life. He was a prolific writer and published seven books of poetry, wrote more than one hundred short stories and copyrighted four plays. In fact, his poem “Only a Miner Killed” has been said to be the basis for Bob Dylan’s song “Only a Hobo”. Only one institutional holding is found on OCLC. Details>>

John Wallace “Jack” Crawford was an American adventurer, educator, and author known as one of the most popular performers in the late nineteenth century. His daring actions to carry the news the 350 miles to Ft. Laramie in six days of General George Crook’s victory in the Battle of Slim Buttes during the Great Sioux War made him instantly famous. After his stints in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and “General Crook’s Horsemeat March,” Crawford served as a special agent for the US Department of Justice, spending four years investigating illegal liquor traffic and fighting alcoholism on Indian reservations. During his work for the US Government, he began his career as an entertainer in 1893 which continued until 1898. He wrote poetry and held “lectures” across the United States where he told of his many adventures in the Wild West, and where he asked his audiences to be careful and foreswear liquor in order to lead a more fulfilled life. He was a prolific writer and published seven books of poetry, wrote more than one hundred short stories and copyrighted four plays. In fact, his poem “Only a Miner Killed” has been said to be the basis for Bob Dylan’s song “Only a Hobo”. Only one institutional holding is found on OCLC. Details>>

Dealings with the Dead

This volume includes collected commentary by noted antiquary and temperance advocate Lucius Manlius Sargent on Boston society (among other things), as was initially published in a series of Boston Evening Transcript articles. Per the DAB, “though he showed enthusiasm for the past, his efforts were generally directed towards blasting something offensive to him out of existence.” This, the first book edition, was published in two volumes in 1856. OCLC records just four copies of this work in institutional hands. Details>>

This volume includes collected commentary by noted antiquary and temperance advocate Lucius Manlius Sargent on Boston society (among other things), as was initially published in a series of Boston Evening Transcript articles. Per the DAB, “though he showed enthusiasm for the past, his efforts were generally directed towards blasting something offensive to him out of existence.” This, the first book edition, was published in two volumes in 1856. OCLC records just four copies of this work in institutional hands. Details>>

Back from the Mouth of Hell

This book’s drop title reads “Or The Rescue from Drunkenness. The Causes, Progress and Results of Intemperance, with the Possibility and Effectual Methods of Accomplishing Permanent Reform.” It was published anonymously in 1878 “By a Former Inebriate.” But this copy bears the an inscription on the ffep from the author, James E. Abbe. The title does not appear in Amerine & Borg. It’s still bound in the publisher’s original half-sheep binding with marbled paper boards and pale peach colored endpapers. Though it has some modest binding wear, mostly to the extremities, it’s withal a Very Good+ copy. Details>>

This book’s drop title reads “Or The Rescue from Drunkenness. The Causes, Progress and Results of Intemperance, with the Possibility and Effectual Methods of Accomplishing Permanent Reform.” It was published anonymously in 1878 “By a Former Inebriate.” But this copy bears the an inscription on the ffep from the author, James E. Abbe. The title does not appear in Amerine & Borg. It’s still bound in the publisher’s original half-sheep binding with marbled paper boards and pale peach colored endpapers. Though it has some modest binding wear, mostly to the extremities, it’s withal a Very Good+ copy. Details>>

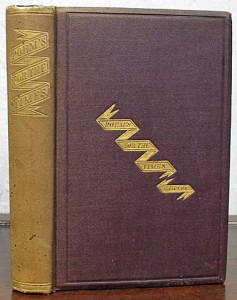

Poems for the Times: Devoted to Woman’s Rights, Temperance, Etc

The author, Frances A Rowley, notes that her purpose is to “touch upon the most, if not all of the great evils of the day, and have placed the language in the poetic form, thinking that perhaps in this way I might reach the minds of those of my sex that would not be as well pleased with the practicabilities in prose…” Poems for the Times is a somewhat uncommon work addressing women’s suffrage, etc. It was first published in 1871. This first edition is bound in the original publisher’s purple cloth with gilt stamping and bevelled edges. The spine is sunned, but otherwise this is a square and tight Very Good+ volume. Details>>

The author, Frances A Rowley, notes that her purpose is to “touch upon the most, if not all of the great evils of the day, and have placed the language in the poetic form, thinking that perhaps in this way I might reach the minds of those of my sex that would not be as well pleased with the practicabilities in prose…” Poems for the Times is a somewhat uncommon work addressing women’s suffrage, etc. It was first published in 1871. This first edition is bound in the original publisher’s purple cloth with gilt stamping and bevelled edges. The spine is sunned, but otherwise this is a square and tight Very Good+ volume. Details>>

Arlington WCTU Cookbook, in Memory of Mother Wilkins

The last page of this cookbook concludes with a recipe for ‘Husbands’: “One of the lectures before the Baltimore Cooking School recently gave this recipe for cooking husbands. A good many husbands are utterly spirited by mismanagements. Some women go about it as if their husbands were bladders, and blow them up. Others keep them constantly in hot water. Others let them freeze by their carelessness and indifference… Tie him in the kettle by a strong silk cord called Comfort, as the one called Duty is apt to be weak. Make a clear, steady fire out of Love, Neatness and Cheerfulness. Set him as near this as seems to agree with him. If he sputters and fizzes, do not be anxious – some husbands do this till they are quite done… Do not stick any sharp instrument into him to see if he is becoming tender. Stir him gently, watching the while, lest he lie to flat and close to the kettle; and so become useless. If thus treated you will find him very relishable, agreeing nicely with you and the children: and he will keep as long as you want, unless you become careless, and set him in too cold a place.” This item is rare in the trade; OCLC records five institutional holdings. Details>>

The last page of this cookbook concludes with a recipe for ‘Husbands’: “One of the lectures before the Baltimore Cooking School recently gave this recipe for cooking husbands. A good many husbands are utterly spirited by mismanagements. Some women go about it as if their husbands were bladders, and blow them up. Others keep them constantly in hot water. Others let them freeze by their carelessness and indifference… Tie him in the kettle by a strong silk cord called Comfort, as the one called Duty is apt to be weak. Make a clear, steady fire out of Love, Neatness and Cheerfulness. Set him as near this as seems to agree with him. If he sputters and fizzes, do not be anxious – some husbands do this till they are quite done… Do not stick any sharp instrument into him to see if he is becoming tender. Stir him gently, watching the while, lest he lie to flat and close to the kettle; and so become useless. If thus treated you will find him very relishable, agreeing nicely with you and the children: and he will keep as long as you want, unless you become careless, and set him in too cold a place.” This item is rare in the trade; OCLC records five institutional holdings. Details>>

Related Posts:

Three Pioneering Authors Who Used Pseudonyms

George Cruikshank: “Modern Hogarth,” Teetotaler, and Philanderer

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.