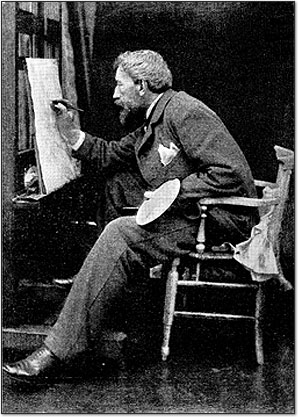

Yesterday the winners of this year’s Newbery and Caldecott Awards were announced. The latter was named for Randolph Caldecott, an accomplished painter and sculptor whose various attainments are often eclipsed by his brilliant carer as an illustrator. Along with figures like Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott was truly one of the most gifted illustrators of the Victorian era.

Yesterday the winners of this year’s Newbery and Caldecott Awards were announced. The latter was named for Randolph Caldecott, an accomplished painter and sculptor whose various attainments are often eclipsed by his brilliant carer as an illustrator. Along with figures like Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott was truly one of the most gifted illustrators of the Victorian era.

Caldecott was born in Chester on March 22, 1846. He was third child by his father’s second wife and would eventually be one of thirteen children. From the time he was young, Caldecott frequently spent his free time sketching and modeling his surroundings. But when Caldecott left school at fifteen years old, it wasn’t to pursue a career in art. He took a position at the Whitchurch branch of the Whitchurch & Ellesmere Bank. Caldecott settled in a nearby village, and he often took time to capture the country scenes that stretched out before him as he traveled to visit clients.

A lover of riding, Caldecott naturally took up hunting. His collected works include, therefore, a huge number of hunting scenes, along with myriad sketches of animals. Caldecott’s first published drawing was of neither; it was of a disastrous fire at the Queen Railway Hotel. Caldecott wrote an account of the blaze for the Illustrated London News. When Caldecott moved to Manchester six years later to work at the Manchester & Salford Bank, he took the opportunity to take night classes at the Manchester School of Art. Soon after, his drawings began appearing in local and London periodicals.

Then in 1870, Caldecott’s friend Thomas Armstrong, a painter in London, introduced Caldecott to Henry Blackburn of London Society. Blackburn and Caldecott got along famously, eventually traveling together. For a time, Caldecott even lived in a cottage at Blackburn’s estate. Blackburn published a number of Caldecott’s illustrations in the magazine, and in 1872 Caldecott decided to move to London and pursue illustration full time. He was 26 years old.

Then in 1870, Caldecott’s friend Thomas Armstrong, a painter in London, introduced Caldecott to Henry Blackburn of London Society. Blackburn and Caldecott got along famously, eventually traveling together. For a time, Caldecott even lived in a cottage at Blackburn’s estate. Blackburn published a number of Caldecott’s illustrations in the magazine, and in 1872 Caldecott decided to move to London and pursue illustration full time. He was 26 years old.

Within two years, Caldecott found himself a prominent magazine illustrator working on commission. His opus is varied, ranging from children’s books to travel illustrations and caricatures. His illustrations for Washington Irving’s Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall (1875) had made his name in the illustration world. Caldecott also illustrated works by Oliver Goldsmith, notably Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog. Caldecott’s illustration of the poem would be used in a World War I parody, in which the head in his original illustration was replaced by the head of the Kaiser of Germany.

Caldecott settled in the heart of Bloomsbury. He was surrounded by artists and literati, regularly encountering figures like Dante Rosetti, George du Maurier, and Frederic Leighton. Lord Leighton would go on to hire Caldecott to design four peacock capitals for the Asia room of Leighton House in Kensington; Walter Crane would design a peacock frieze for the same room.

Caldecott settled in the heart of Bloomsbury. He was surrounded by artists and literati, regularly encountering figures like Dante Rosetti, George du Maurier, and Frederic Leighton. Lord Leighton would go on to hire Caldecott to design four peacock capitals for the Asia room of Leighton House in Kensington; Walter Crane would design a peacock frieze for the same room.

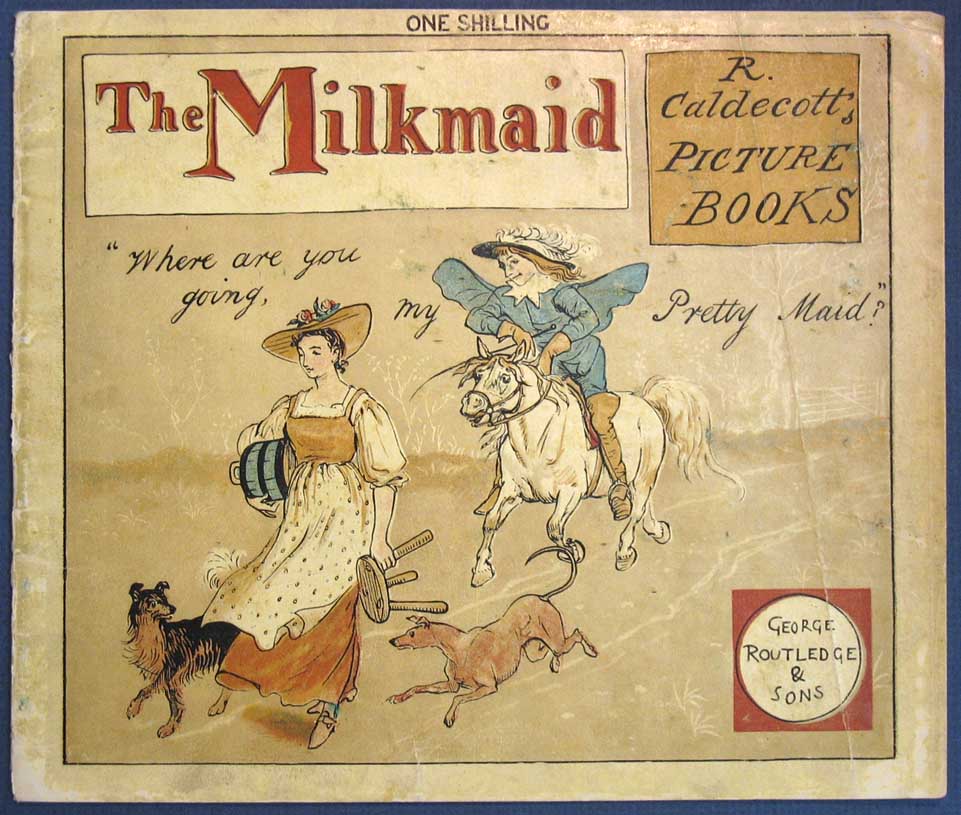

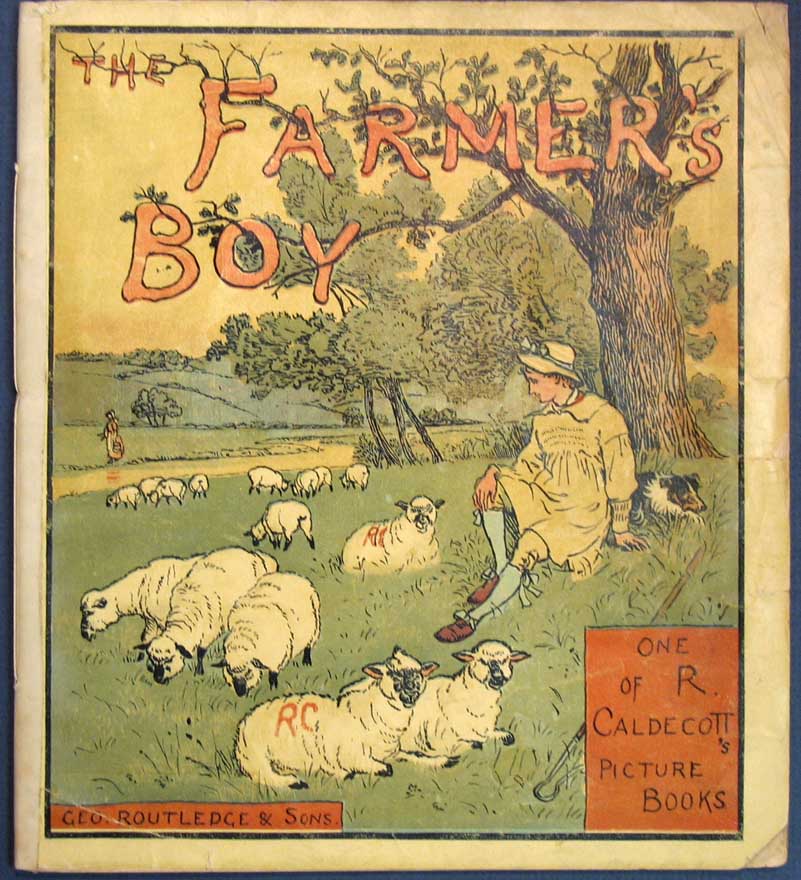

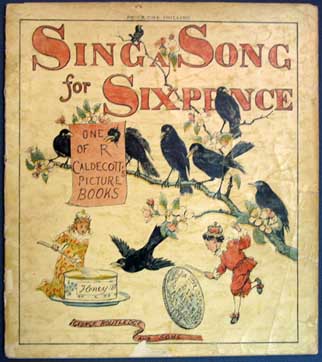

In 1877, accomplished engraver Edmund Evans ended his relationship with illustrator Walter Crane. Evans found Caldecott’s illustrations “racy and spontaneous,” so he invited Caldecott to replace Crane. The first project: two Christmas books. Caldecott took on the work, illustrating The House that Jack Built and the William Cowper poem The Diverting History of John Gilpin. These books were so successful that Caldecott produced two more each Christmas for the rest of his life. Caldecott chose all the stories and rhymes, sometimes even composing them himself.

Combined sales of the Christmas books hit 867,000 during Caldecott’s lifetime. The artist was internationally famous. Caldecott’s publisher, George Routledge & Sons, took Caldecott’s works quite seriously. They took great pains to reproduce the colors exactly as Caldecott had intended. When the books were reissued by Frederick Warner & Co after Caldcott died, they brightened the colors but lost much of the subtlety imbued by Caldecott.

Combined sales of the Christmas books hit 867,000 during Caldecott’s lifetime. The artist was internationally famous. Caldecott’s publisher, George Routledge & Sons, took Caldecott’s works quite seriously. They took great pains to reproduce the colors exactly as Caldecott had intended. When the books were reissued by Frederick Warner & Co after Caldcott died, they brightened the colors but lost much of the subtlety imbued by Caldecott.

Not all Caldecott’s works, however, were commercially successful. In 1883, he undertook an edition of Aesop’s fables. He invited his brother Alfred to translate the tales from the original Greek, but later overruled Alfred’s accuracy. Caldecott’s goal was to make Aesop’s fables, which were often used for instruction, more accessible to children. He illustrated each of the tales he selected with Victorian human behavior. Usually comical, the illustrations illuminated the veracity of Aesop’s teachings. But the book was still too complicated for children, and it did not sell well.

Caldecott’s 1885 edition of The Great Panjandrum Himself fared much better. The nonsense poem by Samuel Foote had become quite the rage among university students, who would try to memorize the lines and recite them to one another. (Generations later, students would take up Winnie-the-Pooh, by AA Milne, with the same fervor; the story was even translated into Latin by one undergraduate.)

Meanwhile, Caldecott’s health was ever precarious. He frequently traveled to warmer climates. It was on one of these trips, in 1886, that he passed away. Caldecott and his wife had arrived in St. Augustine, Florida during a particularly cold February. Caldecott succumbed to the cold, and his memorial still stands in St. Augustine.

Related Posts:

AA Milne: Legendary Children’s Author and Ambivalent Pacifist

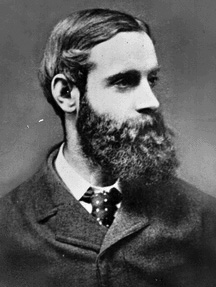

Kate Greenaway: Legendary Illustrator of Children’s Books

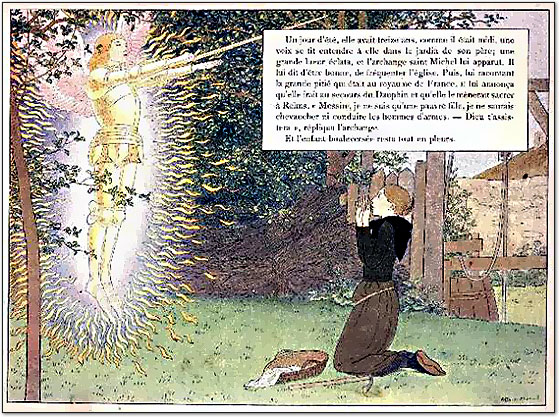

Maurice Moutet de Monvel and His Ingenious ‘Jeanne d’Arc’

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.