September 18 marks the birthday of Samuel Johnson, legendary author, essayist, and lexicographer. Johnson is perhaps best known as the subject of James Boswell’s seminal Life of Johnson, the biography that ushered in a new era for the genre. But before Johnson merited his own biography (indeed, multiple biographies), he got his start by writing a biography himself. Johnson began a strange and relatively short-lived friendship with minor poet Richard Savage, and gained attention by writing Savage’s biography.

An Unlikely Friendship

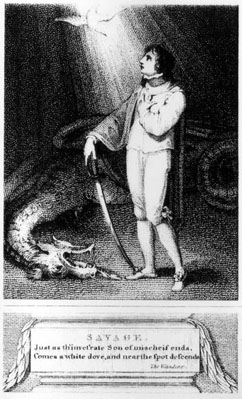

From The Grub Street Journal (Oct 30, 1732), this cartoon depicts the “literatory,” a sort of publishing factory driven by beasts without artistic inspiration. Such was the perception of Grub Street writers like Johnson and Savage, who did indeed scrape together a living from commissioned writing.

Samuel Johnson came to London in 1737, when he was 28 years old. By 1739, he was already separated from his wife (already in her late forties) and scraping by as an impoverished writer in Grub Street. It was during this period of poverty that Johnson befriended Richard Savage. Savage was at least twelve years older than Johnson, and he, too was struggling to make a living with his pen. Savage claimed to be the illegitimate son of the Countess of Macclesfield and the Earl Rivers. Thanks to a sensational public divorce, Savage’s repeated insistence on his ancestry, and the fact that he did in fact receive financial support from the countess, his assertions are rather well corroborated.

Savage found even further notoriety when he killed a man and was sentenced to death. He says that his own mother encouraged a speedy dispatch of her illegitimate son, but Queen Caroline interceded on his behalf. Savage was released, and soon stories of his origins and exploits had taken on a life of their own. Savage’s most famous poem was, appropriately enough, The Bastard.

Etching of proceedings inside the Old Bailey (c 1725)

It’s not clear how or when Johnson and Savage first met. There’s no actual documentation of their meeting in the form of letters, journal entries, or eyewitness accounts. But in Johnson’s later years, the myth developed that Johnson and Savage encountered each other on the street at night. Neither could afford food or lodging, so they passed the nights by wandering through London. Their friendship, however, lasted less than two years. And while Johnson writes of Savage’s nightly walks, he never mentions himself as a companion–he never alludes to the pair’s first meeting at all.

The friendship is unlikely in every sense. Johnson was a devout Christian, hardly a likely companion to a murderer and profligate. It was likely a friendship of proximity, promulgated by shared circumstances. But Life of Savage propelled Johnson to fame, and he remained successful thanks to subsequent works like his momentous Dictionary of the English Language (1755), The History of Rasselas (1759), and The Rambler (1750-1752). Savage, on the other hand, continued to languish as a minor poet. He relentlessly and shamelessly sought the patronage of Robert Walpole and an appointment to the position of poet laureate, but to no avail.

An Empathetic Biographer

Johnson starts his biography with a sort of meditation on Savage’s nightly perambulations around London. He places these excursions in the context of Savage’s poem “Of Public Spirit,” which considers the state’s responsibility to care for the poor and indigent and questions the Whig policy of expatriating the underprivileged to North America and Africa. Savage goes so far as to attack colonialism, countering the popular rationalization that “while they enslave, they civilize.” It’s quite fitting that “Of Public Spirit” sold only 72 copies, underlining Savage’s status as a nonentity. Savage himself was disenfranchised, and Johnson saw him as a spokesman for the downtrodden. Johnson’s latent empathy for Savage betrays his own familiarity with such destitution.

Yet while Johnson writes of Savage’s nightly walks, he never mentions himself as a companion–he never alludes to the pair’s first meeting at all. By the time he set about writing Savage’s biography, he had already realized the need to distance himself from Savage. Johnson wrote, “it was always dangerous to trust him, because he considered himself discharged, by the first Quarrel, from all Ties of Honour or Gratitude.”

Thus, while Johnson saw Savage as a Romantic figure, a starving-poet archetype, he never got taken by him. A great appeal of Life of Savage was that tension between Johnson as biographer and Johnson as friend; he constantly walked a line between judgement and empathy. This approach was certainly uncommon; biographies tended to aggrandize their subjects, glossing over shortcomings. Johnson also departed from the classic form of biography, drawing influences instead from distinctively English sources: elements of Newgate confessions, scandal romances, and courtroom dramas all crop up in Life of Savage. Johnson’s innovation resulted in a biography that was as readable as a novel.

A Role Reversal

Fast forward almost twenty years, to May 16, 1763. Johnson was 53 years old. He entered Tom Davies’ bookshop and encountered the 22-year-old James Boswell. The Scottish Boswell had entreated Davies to keep his heritage a secret; he knew that Johnson disliked Scots. But Davies laughed off the request and made a very casual introduction. The meeting affected Boswell deeply, just as Johnson’s first interaction with Savage had likely affected Johnson profoundly. Boswell wrote of the experience later, noting that Johnson was “a Man of most dreadful appearance. He is very slovenly in his dress and speaks with a most uncouth voice. Yet his great knowledge, and strength of expression command vast respect and render him excellent company.”

Boswell resolved to record further details of his interactions with Johnson, an endeavor that would later result in eighteen volumes of documentation over their long friendship. It’s important to note that Boswell only spent approximately 250 days with Johnson, which illustrates how truly fastidious he was in recording the details of Johnson’s life. When Boswell undertook Johnson’s biography, he overcame the challenge of having met Johnson later in life by conducting extensive research. Despite apparently possessing all the “truth” of Johnson’s life, Boswell still took liberties with Johnson’s life. He censured some of Johnson’s less politically correct comments and omitted some events altogether.

In “The Mitre Tavern” (1880), Samuel Johnson (far right) converses with James Boswell (center) and author Goldsmith.

Yet Boswell wasn’t the first to attempt a biography of Samuel Johnson. Other much more illustrious authors, namely Horace Walpole, Elizabeth Montagu, and Frances Burney, were all working on biographies. And Sir Richard Hawkins had already beaten Boswell to the punch. The two, it turns out, didn’t agree on much–except that Johnson’s relationship with Savage was completely inexplicable. Though they presented disparate accounts of Johnson’s first meeting with Savage (and Johnson himself did nothing to elucidate the matter), their estimation of Savage is perhaps best distilled by Boswell: he called Savage “a man of whom it is difficult to speak impartially, without wondering that he was for some time the intimate companion of Johnson; for his character was marked by profligacy, insolence, and ingratitude.”

When Boswell finally published Life of Johnson in 1791, the work was truly exhaustive. Boswell set a new standard for biography, insisting upon the importance of details, of acknowledging that the minutiae are ultimately part of the big picture of someone’s character and personhood. His work now stands as the greatest biography in the English language, perhaps, as some think, eclipsing even the work of Johnson himself.

Photo: Bustamante Shows

Photo: Bustamante Shows