The nineteenth century was a time of exploration and discovery in the field of medicine. One man who made significant contributions to the field in America was Elias Samuel Cooper, a surgeon whose aspirations stretched beyond building a successful private practice. Dr. Cooper founded the first medical college in San Francisco, where his techniques drew both controversy and respect from the medical community.

The nineteenth century was a time of exploration and discovery in the field of medicine. One man who made significant contributions to the field in America was Elias Samuel Cooper, a surgeon whose aspirations stretched beyond building a successful private practice. Dr. Cooper founded the first medical college in San Francisco, where his techniques drew both controversy and respect from the medical community.

Self-Education and Training

Cooper was raised on a Quaker farm in Ohio, where his abolitionist family settled after relocating from slavery-friendly South Carolina in 1807. His sister lived on a neighboring farm, so Cooper grew up with his nephew, Levi Cooper Lane. Cooper left no personal account of his life, so what we know is gleaned from his brother’s journal and a few other historical sources. From that document, we learn that Cooper’s birthday was November 25, 1820. It’s presumed that Cooper attended a country school in Butler County. His brother Jacob’s journal also refers to Cooper’s apprenticeship to a Dr. Waugh in 1838. Cooper’s older brother Elaias also entered the medical profession, and it appears that Cooper either apprenticed or partnered with him in Greenville, Indiana from 1840 to 1843.

In 1851, Cooper was awarded a medical degree from St. Louis University. At that time, a candidate who got credit for “four years of reputable practice” could obtain a degree after only one lecture cycle, which lasted four-and-a-half months. That seems like little training for such an important profession, but most medical practitioners at the time had no formal training, or little more than an apprenticeship. Cooper had actually “self-awarded” himself an MD at least two years earlier; he published “Remarks on Congestive Fever” in the Jan/Feb 1849 edition of St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal. He signed it “ES Cooper, MD.” Such a practice was relatively common, and it was not until later that more rigorous standards were implemented to prevent self-credentialing and practicing without proper instruction.

By all accounts, Cooper was an incredibly industrious physician, spending many hours in self-study. He was particularly interested in surgery. In 1843, Cooper set up his private practice in Danville, Indiana. Soon he was making almost $800 a month, a tidy sum at the time. At only 23 years old, Cooper performed an impressive surgery, successfully removing a large portion of the patient’s jaw. The procedure required sophisticated knowledge of anatomy, including deep knowledge of the vascular system. Cooper’s success sealed his local reputation in the medical community.

Greater Aspirations

Cooper moved to Peoria, Illinois in 1844, and within a year he’d opened up a dissecting room and begun offering lectures on anatomy and surgery. Less interested in growing his private practice, Cooper focused more heavily on surgery. His first operation was on a case of strabismus (when the eyes are not aligned properly). Soon Cooper had established himself as the preeminent surgeon for the eyes and face, and for orthopedics. Patients would travel from neighboring states to see the young physician.

Cooper’s reputation raised the ire of his colleagues, who decided to attack Cooper for his dissections. At the time, it was legal for surgeons to dissect the bodies of convicts, provided that the relatives had no objections. Thus when convicted murderers Thomas Brown and George Williams were executed, Cooper received their bodies. He removed them under cover of darkness, because the executions had been quite a public spectacle (and had almost taken place at the hands of an angry mob instead of at the hands of sanctioned officials). Cooper had anticipated receiving the bodies, and he’d advertised an anatomy lecture to take place shortly after the execution. Thus, everyone knew where these bodies came from.

But there were no criminals available for Cooper’s next lecture, which raised suspicion of grave robbery. Cooper’s detractors published a handbill called “Rally to the Rescue of the Graves of Your Friends,” drawing attention to the fact that Cooper must be digging up bodies to supply himself with dissection subjects for his numerous anatomy lectures. The handbill called for a public indignation meeting. Cooper attended the meeting himself, along with some of his friends, who were labeled “Cooperites.” One of his companions, who happened to be drunk, offered to preside over the proceedings. When it was suggested that he was unfit for the task, he retorted, “A drunken man may get sober, but a nature-born fool will never have any sense, by God!” The crowd roared with laughter and soon dispersed. This was Cooper’s first brush with controversy, but it wouldn’t be his last.

Cooper’s practice continued to grow, and he had to purchase a second building to house his Infirmary for the Eye and Ear. He also specialized in the removal and correction of deformities from the lower extremities, especially club foot. But his goal was to establish a medical school, so in 1854 Cooper went to Europe to observe the medical institutions there and to meet with leading medical practitioners. When he returned to the United States, he settled in San Francisco.

The First Medical School in San Francisco

After relocating to San Francisco, Cooper established the Cooper Eye, Ear, and Orthopedic Infirmary in a prominent location. He immediately began advertising for free lectures and demonstrations of his surgical techniques, a strategy that didn’t earn him any friends in the local medical community. Cooper also published reports of his various surgical endeavors. One of these was “Report of an Operation to Remove a Foreign Body from Beneath the Heart.” Published by the San Francisco County Midico Chirugical Association in 1857, the report details how Cooper removed an iron slug lodged in the patient, BT Beal, for 74 days before Cooper endeavored to remove it. The patient’s health improved so dramatically after the procedure that he was “not to be recognized by the medical men present at the operation.”

After relocating to San Francisco, Cooper established the Cooper Eye, Ear, and Orthopedic Infirmary in a prominent location. He immediately began advertising for free lectures and demonstrations of his surgical techniques, a strategy that didn’t earn him any friends in the local medical community. Cooper also published reports of his various surgical endeavors. One of these was “Report of an Operation to Remove a Foreign Body from Beneath the Heart.” Published by the San Francisco County Midico Chirugical Association in 1857, the report details how Cooper removed an iron slug lodged in the patient, BT Beal, for 74 days before Cooper endeavored to remove it. The patient’s health improved so dramatically after the procedure that he was “not to be recognized by the medical men present at the operation.”

Clearly Cooper had developed an incredible talent for the art of surgery, but he also made notable advancements to the field. He helped to introduce the use of chloroform during surgery, an indispensable tool in the days before general anesthesia. Cooper also used alcoholic dressings to prevent infection to incisions and wounds, significantly reducing mortality rates. He was a pioneer in the use of animals to test surgical techniques. In 1858, Cooper used his connections and knowledge to establish the Medical department of the University of the Pacific. The school has existed under several names almost without interruption ever since.

Though Cooper still drew some criticism for his dissections, he worked to clarify regulations and ensure proper practices in California. But that didn’t mean that he received universal approbation. In 1857, Cooper performed San Francisco’s first caesarean section. The mother, Mary Hoges, survived but her child did not. Thanks to the encouragement of Dr. David Wooster, who had been the assisting physician, Hoges sued Cooper for malpractice. She argued that the procedure had been unnecessary. The trial resulted in a hung jury, but Wooster continued to publicly attack Cooper, whom he considered a rival. Cooper finally responded in The San Francisco Medical Press, which he founded himself.

Cooper’s career was cut short in 1862, when he succumbed to nephritis after a prolonged illness. But his contributions to medical literature offer fascinating insights into the evolution of the field.

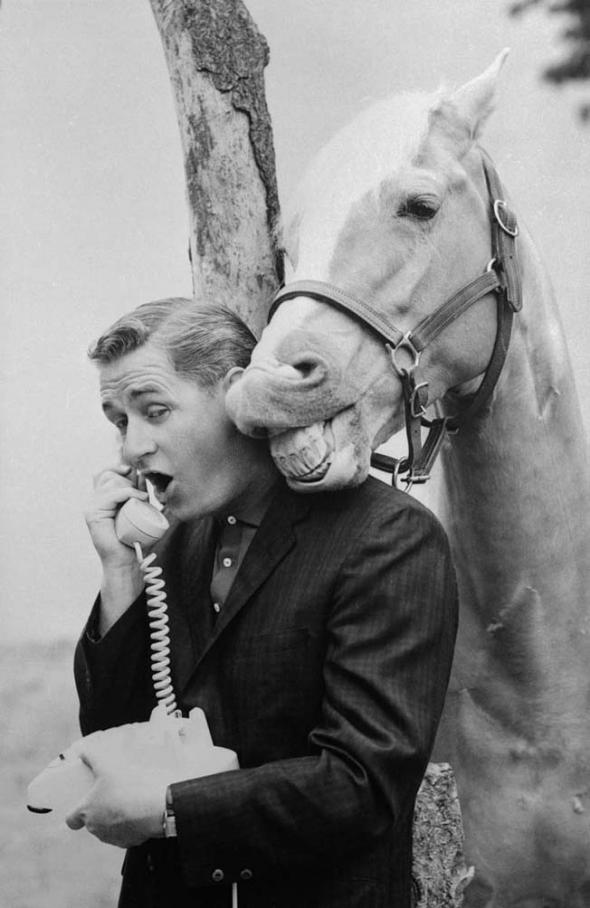

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.”

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.” The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.

The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.