On this day, 487 years ago, a king was on a rampage. He was condemning non-believers. Not those who didn’t believe in God or religion, but those who didn’t believe in his divorce and therefore the new religion that he was shaping in order to get one. That’s right, King Henry VIII was in the middle of his divorce from Queen Katherine of Aragon and it was not a good time for those who opposed this nullification and the king’s appointment as Head of the Church of England. One such man was Thomas More, Chancellor of England, humanitarian, lawyer, writer, and statesman. As author of Utopia, More had a definitive idea in mind of the perfect society – let’s delve into what this was, and what his execution meant for England.

Thomas More was born on the 7th of February, 1478, the second of six children to a well-regarded lawyer. More received a classical education, and was a page to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who recommended him for a University education – prompting More to attend Oxford in 1492. He left after only two years, but those short years were more than enough time for More to become proficient in both Latin and Greek, as well as instruct himself in the fine etiquette of society. He began his legal education in London instead, at his father’s insistence.

It would be worth noting that by this time More had a significant interest in the spiritual realm. According to one of his friends at school he was seriously considering leaving his burgeoning legal profession to spend his life as a monk. Despite ultimately deciding that he would live his life as a layman, he kept up some of the more rigorous practices of the church, occasionally using self-flagellation as a cleansing tool, and wearing a rough hair shirt as a symbol of repentance. Although some aspects of his life might have looked severe to an onlooker, More himself was thought of as a warm, good natured (if stoic) person. He was a loving father, and had four children of his own, adopted another daughter upon his second marriage to a widow, and took two other children further under his wing. He gave all of his children (the girls as well as the boys) extremely detailed tuition, his extremely intelligent daughters and his pride in their accomplishments setting a new standard for female education throughout the country. More spent as much time with his family as his lifestyle could allow – for in 1504 he was elected to Parliament and in the short years that followed experienced a great rise in his value and influence to the nation. In 1516 he published his famed work Utopia in Latin, a work that wouldn’t be translated into English until almost twenty years after his death. Utopia depicted a perfect society – a place of total harmony, without the need for lawyers, with education to all sexes alike and religious tolerance. The work itself is actually hailed as the start of dystopian literature, a popular genre still today. By 1521 More was a close confidant and personal adviser to King Henry VIII.

Thomas More as painted by Hans Holbein the Younger

More’s support of the Catholic church led to his position as a staunch Anti-Protestant advocate. He and Henry VIII together led extreme responses to Martin Luther’s publications, burning the books and those that openly supported the German “heretic”. More enjoyed over a decade of his position in the royal household, until it all came crashing down. In 1530, More refused to sign a letter signed by other members of the English aristocracy, begging the Pope to annul Henry and Catherine’s marriage. More then refused to sign the Oath of Supremacy, giving Henry just cause to reign higher than the Pope in the matter of his marriage. Despite More’s personal beliefs, he did not openly condemn the King’s actions, or refuse to acknowledge his divine rights as King. This balancing act was the only thing that kept More safe for as long as he was. He resigned from his position as Chancellor in May of 1532, realizing that he couldn’t show support for actions he did not believe in, nor could he condemn them. He (gentlemanly, sending his regrets) refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn in 1533, and in 1534 when he was asked to trial to swear his allegiance to the Act of Succession, More continued to refuse to take the Oath of Supremacy, acknowledging the Church of England over papal rule and Queen Anne’s offspring as rightful heirs to the English throne. Balancing act now over, this was unfortunately the act of treason his enemies (Thomas Cromwell, for one) had been waiting for – and the court appointed to try Thomas More took only 15 minutes to condemn him to death.

We know the rest of the story, but what did his death mean for the world? Well, for one, the imprisonment of Cardinal Wolsey and then the imprisonment and execution of Thomas More did much to unsettle the country. Both men had been great friends and confidants of the King, and their deaths are occasionally credited with instilling a fear in the English aristocracy. Thomas More in particular, was an innocent man. Unlike Wolsey, More was never accused of financial shadiness, nor did he have a false sense of his own importance or worth. He was a man of relatively simple pleasures, and his only crime was sticking to his beliefs, which, until Henry VIII settled on divorcing his wife, were shared by the King as well. More has since been martyred in the Catholic church for remaining true to his faith, even in the face of certain death. If you ask us, the execution of Thomas More is one of the saddest in history.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

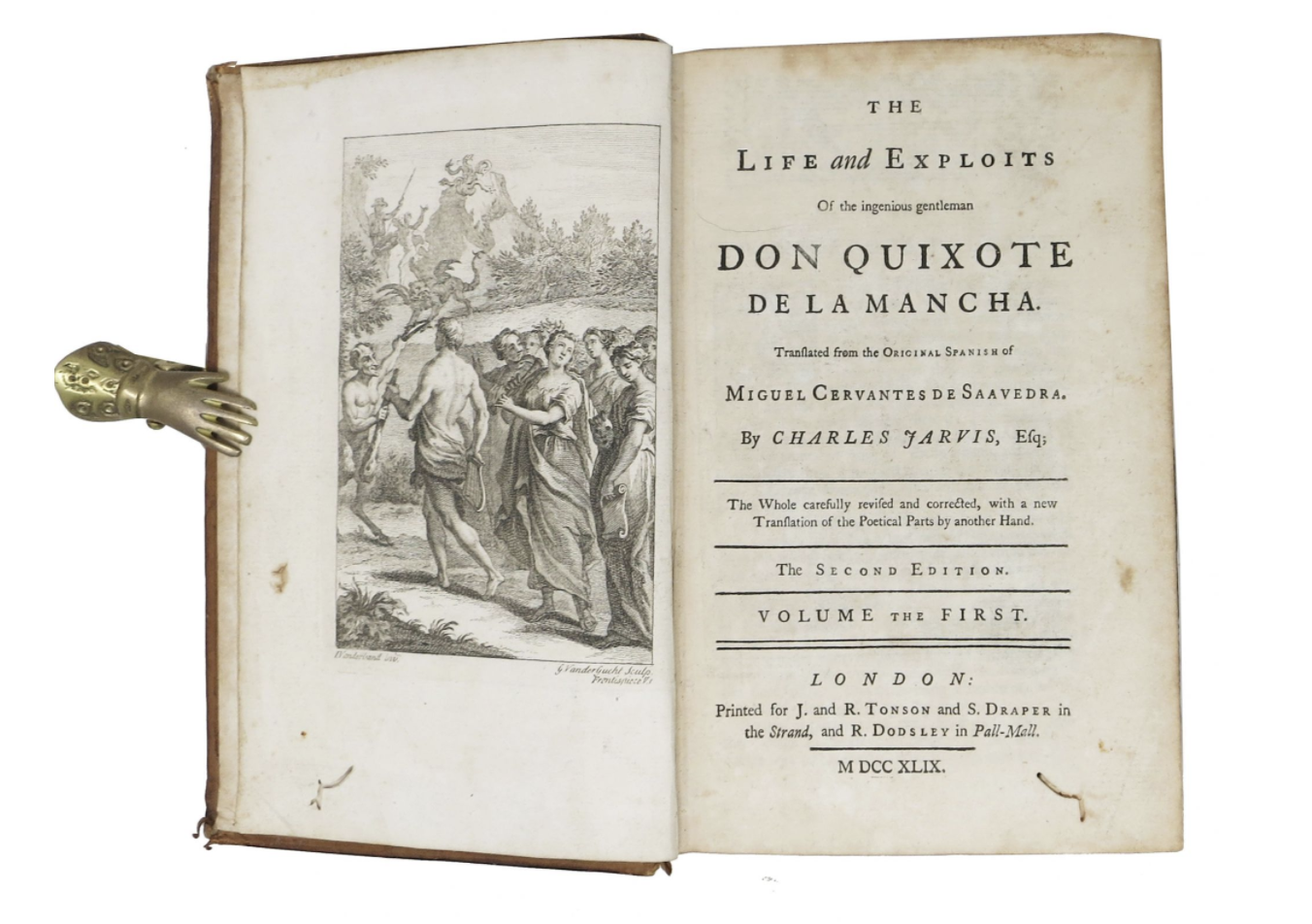

Throughout this time, Cervantes published a few plays and some poems, none of any great significance, and none that provided a living for the man and his family. By 1605, Cervantes hadn’t been “properly” published in almost 20 years! Nevertheless, he began writing a work he considered a satire – he challenged a “form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romances. He wrote about the common man. He used everyday lingo, normal conversation rather than epic speeches – it was considered a great success. Though there was a great amount of time between the two parts of the work, its popularity did not wane. The first part is considered the more popular of the two, with its comedic characterizations and its hilarity, while the second part is considered more introspective and critical, with greater characterization of the individuals in the story.

Throughout this time, Cervantes published a few plays and some poems, none of any great significance, and none that provided a living for the man and his family. By 1605, Cervantes hadn’t been “properly” published in almost 20 years! Nevertheless, he began writing a work he considered a satire – he challenged a “form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romances. He wrote about the common man. He used everyday lingo, normal conversation rather than epic speeches – it was considered a great success. Though there was a great amount of time between the two parts of the work, its popularity did not wane. The first part is considered the more popular of the two, with its comedic characterizations and its hilarity, while the second part is considered more introspective and critical, with greater characterization of the individuals in the story.

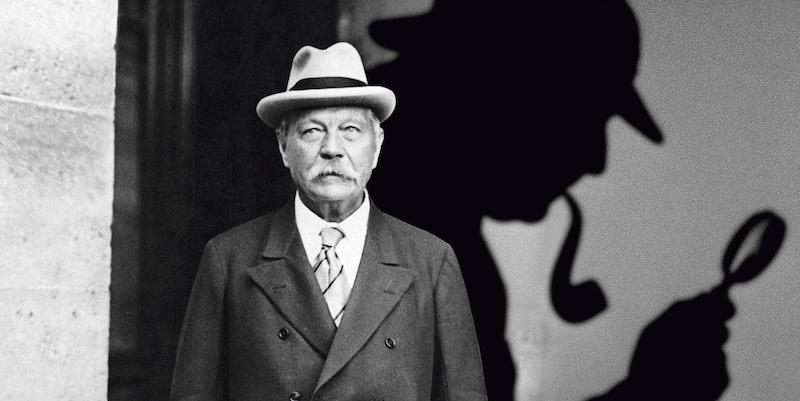

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his first Sherlock Holmes installment, A Study in Scarlet, when he was only 27 years old. Written in just under three weeks, it is amazing to think that on how this work has endured and began a legacy, a series the likes of which may be unparalleled in fiction. A Study in Scarlet was popular and successful, and Conan Doyle was commissioned to write a sequel in less than a year. The next work, The Sign of the Four, was no less popular when it appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine. Amusingly enough, even early on in his Holmes works Conan Doyle felt contradictory emotions towards his most famous character. He wished to kill Holmes off after just a couple years, but was dissuaded (more like forbade) from doing so by his own mother! He raised the prices for his stories hoping to dissuade publishers from paying for them, but found that publishers were willing to pay exorbitant sums to keep the stories coming… consequently Conan Doyle accidentally became one of the best paid authors of all time. In all, Conan Doyle featured Sherlock Holmes (often against his will – public outcry was so great after Doyle had Holmes and Moriarty plunge off a cliff together that Holmes was forced to resurrect his famed detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles years later) in fifty-six short stories and four novels – a long and eventful life for a fictional character!

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his first Sherlock Holmes installment, A Study in Scarlet, when he was only 27 years old. Written in just under three weeks, it is amazing to think that on how this work has endured and began a legacy, a series the likes of which may be unparalleled in fiction. A Study in Scarlet was popular and successful, and Conan Doyle was commissioned to write a sequel in less than a year. The next work, The Sign of the Four, was no less popular when it appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine. Amusingly enough, even early on in his Holmes works Conan Doyle felt contradictory emotions towards his most famous character. He wished to kill Holmes off after just a couple years, but was dissuaded (more like forbade) from doing so by his own mother! He raised the prices for his stories hoping to dissuade publishers from paying for them, but found that publishers were willing to pay exorbitant sums to keep the stories coming… consequently Conan Doyle accidentally became one of the best paid authors of all time. In all, Conan Doyle featured Sherlock Holmes (often against his will – public outcry was so great after Doyle had Holmes and Moriarty plunge off a cliff together that Holmes was forced to resurrect his famed detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles years later) in fifty-six short stories and four novels – a long and eventful life for a fictional character!