The Berkeley City Club – a beautiful venue, as usual!

What could be better than a group of bibliophiles gathered together in a single room to celebrate the holiday season? A group of booksellers gathered together in a single room celebrating the holiday season with good food and a raffle of lots of alcohol, that’s what! Just kidding! In all honesty though we all (as adults) enjoy our bottles of wine and bourbon, what we truly enjoy is spending time with like-minded individuals. The NCC Chapter of the ABAA Holiday Dinner was no exception!

This year the bar, being held in the same large room as the dinner, seemed to be a bit more of an intimate affair (which I rather enjoyed). The large table of donations for the Elizabeth Woodburn / ABAA Benevolent Fund raffle was overflowing – as usual with impressive selections of beverages, but with also some fun gift baskets and chocolates, 2018 SF Giants baseball tickets, etc., etc! Many raffle tickets were sold (most to our table mates John Windle and co., in my opinion – winners galore!!!) But I get ahead of myself.

This year the bar, being held in the same large room as the dinner, seemed to be a bit more of an intimate affair (which I rather enjoyed). The large table of donations for the Elizabeth Woodburn / ABAA Benevolent Fund raffle was overflowing – as usual with impressive selections of beverages, but with also some fun gift baskets and chocolates, 2018 SF Giants baseball tickets, etc., etc! Many raffle tickets were sold (most to our table mates John Windle and co., in my opinion – winners galore!!!) But I get ahead of myself.

First things first Michael Hackenberg, the Chapter Chair, introduced the evening with his wit and charm. Minutes of the last meeting were approved, and one great new piece of information that was praised was the recent repeal of the most egregious parts of the California law on signed material. Unfortunately getting the bill repealed has cost quite a bit of funds for the ABAA, most of which were spent on lobbyists! But in any case, everyone is quite happy that we are on our way to normality back in the signed and autographed world of rare books. Another topic of interest covered is that the ILAB Congress in LA next year is close to being sold out! There are possibly one or two more seats to be had, and those who have been agree that it is a wonderful destination work-trip for any book related people. Over 100 people have signed up thus far.

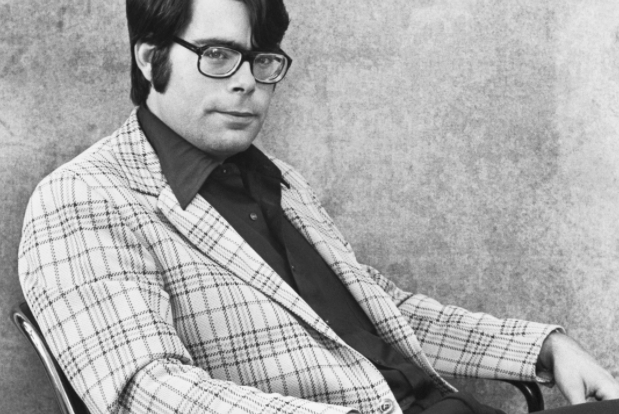

An image of a very happy (possible) ABAA President?!

New members of the ABAA board will soon be voted on! Members of the NCC that are up for nomination in different positions include our very own Vic Zoschak [as President], Michael Hackenberg [as our Chapter Rep], Brad Johnson & Scott deWolfe are both competing for the ABAA VP slot, and Peter Blackman is on the ballot as Association Treasurere. The NCC Board includes Andrew Langer as the new treasurer, Alexander Akin continuing on as Secretary, Laurelle Swan as the new Vice Chair, and Ben Kinmont as the new Chair! Congratulations to these four! Another interesting topic included the different showcases touted by several booksellers for this upcoming year include the Bibliography week showcase in January and the RBMS showcase in New Orleans! Last but not least, the upcoming fair in Pasadena in February has one of the highest registrations for several years, with over 200 booksellers registered to exhibit at this time. Woohoo!

In all, the dinner, the chat, the raffle interspersed between rounds of discussion (a great new idea, in my not so humble opinion), and the camaraderie always found in this group of people made for a wonderful holiday evening.

And to all a good night! (Or afternoon… you catch my drift.)

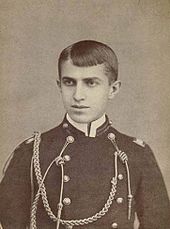

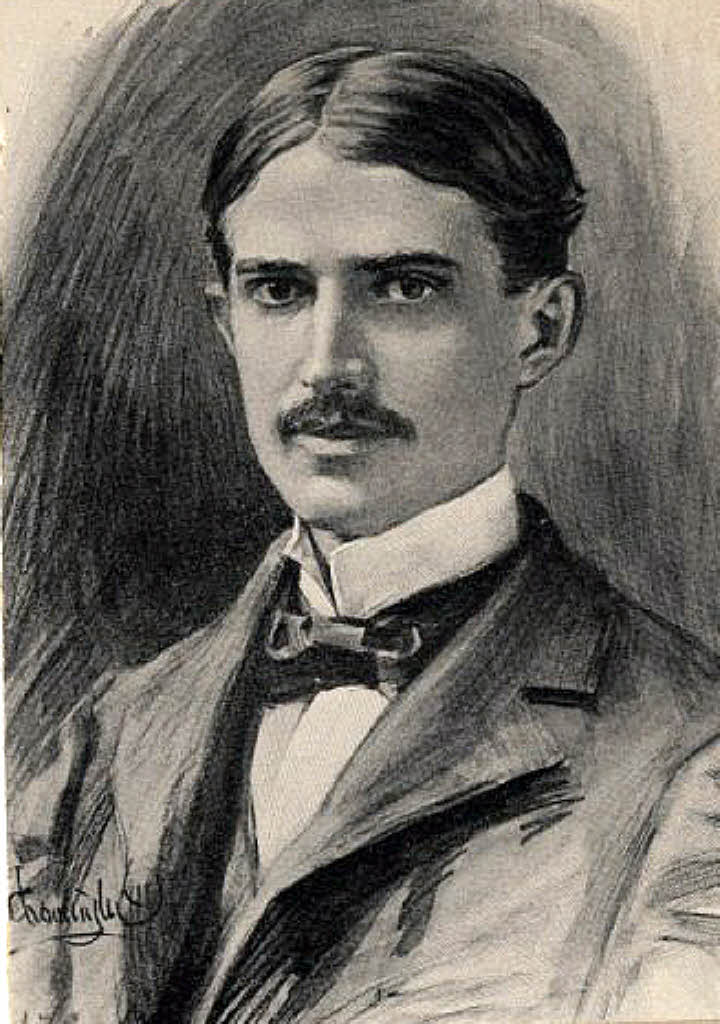

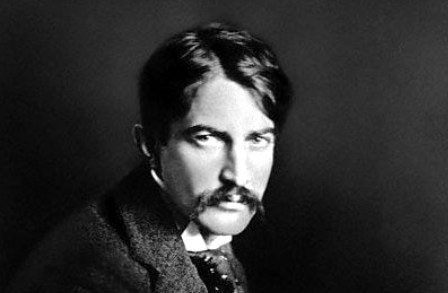

Crane was born on November 1st, 1871 in Newark, New Jersey, the 14th child (of only 8 surviving children) to a clergyman and daughter of a clergyman. Crane began writing at an early age, and when he was eight years old he wrote his first surviving poem – “I’d Rather Have A-” – a poem about wanting a dog for Christmas! One year later he began formal schooling and completed two grades within a six week period. Throughout Crane’s education he was a slightly erratic student, if intelligent and somewhat popular. This could be put down to the fact that by the time Crane was a teen, quite a few members of his family (his father and siblings) were dead – leading to a very different childhood than his classmates.

Crane was born on November 1st, 1871 in Newark, New Jersey, the 14th child (of only 8 surviving children) to a clergyman and daughter of a clergyman. Crane began writing at an early age, and when he was eight years old he wrote his first surviving poem – “I’d Rather Have A-” – a poem about wanting a dog for Christmas! One year later he began formal schooling and completed two grades within a six week period. Throughout Crane’s education he was a slightly erratic student, if intelligent and somewhat popular. This could be put down to the fact that by the time Crane was a teen, quite a few members of his family (his father and siblings) were dead – leading to a very different childhood than his classmates. In 1893 Crane became frustrated with stories written about the Civil War, stating “I wonder that some of those fellows don’t tell how they felt in those scraps. They spout enough of what they did, but they’re as emotionless as rocks.” Crane decided to write an account of a soldier in the war, and began work on what would become The Red Badge of Courage, Crane’s most beloved work to date. His story would be different from his contemporaries – for he wanted desperately to present a “psychological portrayal of fear” by describing a young man disillusioned by the harsh truths of war. He succeeded and a year later his novel began to be published in serial form by the Bacheller-Johnson Newspaper Syndicate. It was heavily edited for publication in the serial, though it did begin to cause a stir in its readers. Crane then worked on a book of poetry, which was published to large amounts of criticism due to his use of free verse, not then a common convention. Crane was not bothered by its unpopular reception – he was instead quite pleased that the book made “some stir” and caused a reaction of any sort. In 1895 Appleton published The Red Badge of Courage, the full chapters, in book form – and Crane became a household name overnight. The book was in the “top six on various bestseller lists around the country” for months after its publication. It even became popular abroad and was widely read in Great Britain as well. Crane was only 23 years old at the start of his fame.

In 1893 Crane became frustrated with stories written about the Civil War, stating “I wonder that some of those fellows don’t tell how they felt in those scraps. They spout enough of what they did, but they’re as emotionless as rocks.” Crane decided to write an account of a soldier in the war, and began work on what would become The Red Badge of Courage, Crane’s most beloved work to date. His story would be different from his contemporaries – for he wanted desperately to present a “psychological portrayal of fear” by describing a young man disillusioned by the harsh truths of war. He succeeded and a year later his novel began to be published in serial form by the Bacheller-Johnson Newspaper Syndicate. It was heavily edited for publication in the serial, though it did begin to cause a stir in its readers. Crane then worked on a book of poetry, which was published to large amounts of criticism due to his use of free verse, not then a common convention. Crane was not bothered by its unpopular reception – he was instead quite pleased that the book made “some stir” and caused a reaction of any sort. In 1895 Appleton published The Red Badge of Courage, the full chapters, in book form – and Crane became a household name overnight. The book was in the “top six on various bestseller lists around the country” for months after its publication. It even became popular abroad and was widely read in Great Britain as well. Crane was only 23 years old at the start of his fame. Crane became a war correspondent alongside Taylor in the Greek-Turkish War of 1897, and then the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Crane became a war correspondent alongside Taylor in the Greek-Turkish War of 1897, and then the Spanish-American War in 1898.

King then had his novel The Shining published in 1977, and The Stand in 1978. In the late 1970s King began a series, eventually known as The Dark Tower, a series which would span the next four decades of King’s life finally ending in 2004. In 1980 King’s novel Firestarter was published, and in 1983 his novel Christine was published – both by the large and well-known publisher Viking. He tried his hand at working on comic books, writing a bit for the X-men series Heroes for Hope in 1985. King published under several pseudonyms for various reasons (now keep a lookout for these names, you hear?) including Richard Bachman (after Bachman-Turner Overdrive), John Swithen (a character out of Carrie) and Beryl Evans (which King used to publish the book Charlie the Choo-Choo: From the World of the Dark Tower). Though he has written many, many works over the years (54 novels, 6 non-fiction books and 200 short stories, to put it bluntly), some of the more popular stories whose names you might recognize (due to their being transferred to the big screen or otherwise) are Children of the Corn (1977), Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redepmtion (1982), Misery (1987), The Man in the Black Suit (1994), The Green Mile (1996), Bag of Bones (1998), and his memoir On Writing (2000). And this doesn’t even scratch the surface of the volume of work King has produced over the past many decades.

King then had his novel The Shining published in 1977, and The Stand in 1978. In the late 1970s King began a series, eventually known as The Dark Tower, a series which would span the next four decades of King’s life finally ending in 2004. In 1980 King’s novel Firestarter was published, and in 1983 his novel Christine was published – both by the large and well-known publisher Viking. He tried his hand at working on comic books, writing a bit for the X-men series Heroes for Hope in 1985. King published under several pseudonyms for various reasons (now keep a lookout for these names, you hear?) including Richard Bachman (after Bachman-Turner Overdrive), John Swithen (a character out of Carrie) and Beryl Evans (which King used to publish the book Charlie the Choo-Choo: From the World of the Dark Tower). Though he has written many, many works over the years (54 novels, 6 non-fiction books and 200 short stories, to put it bluntly), some of the more popular stories whose names you might recognize (due to their being transferred to the big screen or otherwise) are Children of the Corn (1977), Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redepmtion (1982), Misery (1987), The Man in the Black Suit (1994), The Green Mile (1996), Bag of Bones (1998), and his memoir On Writing (2000). And this doesn’t even scratch the surface of the volume of work King has produced over the past many decades.

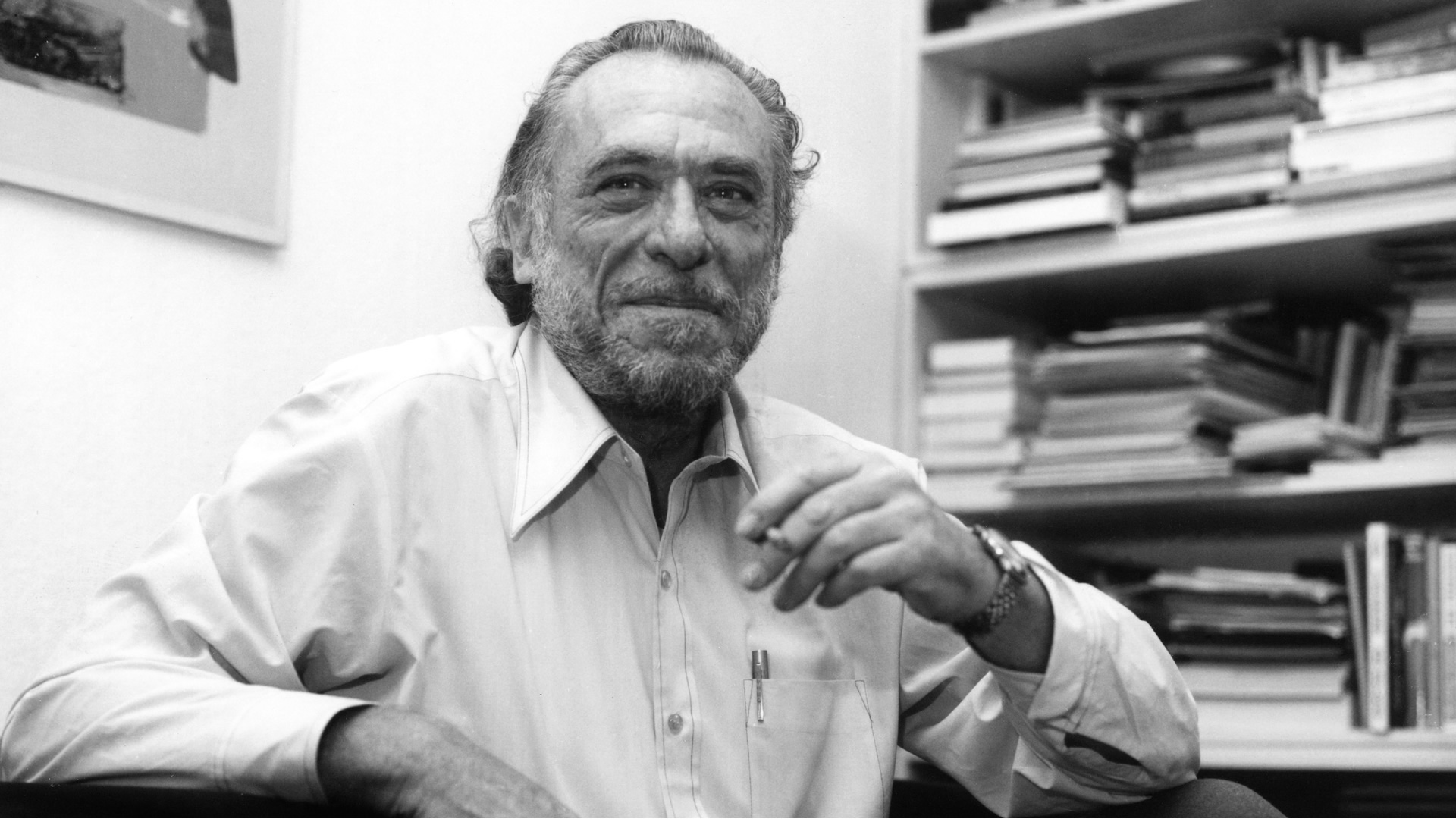

Heinrich Karl Bukowski was born on August 16th, 1920 in Germany. His father, a member of the U.S. Army that remained in Germany after WWI, and his mother brought him to the United States at the tender age of two. Bukowski was a slight child with a poor complexion, often bullied by his peers and beaten by his father who believed in a heavy hand when correcting his child’s faults.

Heinrich Karl Bukowski was born on August 16th, 1920 in Germany. His father, a member of the U.S. Army that remained in Germany after WWI, and his mother brought him to the United States at the tender age of two. Bukowski was a slight child with a poor complexion, often bullied by his peers and beaten by his father who believed in a heavy hand when correcting his child’s faults. In 1959 Bukowski (or Hank, as he was to his friends) published his first book of poetry, Flower, Fish and Bestial Wail, truly establishing himself as a poet, and also dealing with such simple themes as abandonment and desolation in a sad world where all are alone. (No big deal.) He showed his writing style that had changed little but perhaps in the more modern times was more easily accepted – he had a “crisp, hard voice; an excellent ear and eye for measuring out the lengths of lines; and an avoidance of metaphor where a lively anecdote will do the same dramatic work” (Ken Tucker). He continued to publish books of poetry in the upcoming decades, producing a staggering number of books of poetry, as well as those of prose and novels. The subjects of his work remained the same – he lived the life of the poor and the down-trodden, associating himself with drinking, drugs, music, violence, prostitution and gambling. According to Adam Kirsch, Bukowski described his own readership as “the defeated, the demented and the damned.” His first book of short stories was published in 1972 and entitled Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions, and General Tales of Ordinary Madness. In general, his works were often offensive, violent and sordid, but did a few amazing things… brought awareness to the lives of the down-and-out and opened up the literary world to an entirely different style of writing.

In 1959 Bukowski (or Hank, as he was to his friends) published his first book of poetry, Flower, Fish and Bestial Wail, truly establishing himself as a poet, and also dealing with such simple themes as abandonment and desolation in a sad world where all are alone. (No big deal.) He showed his writing style that had changed little but perhaps in the more modern times was more easily accepted – he had a “crisp, hard voice; an excellent ear and eye for measuring out the lengths of lines; and an avoidance of metaphor where a lively anecdote will do the same dramatic work” (Ken Tucker). He continued to publish books of poetry in the upcoming decades, producing a staggering number of books of poetry, as well as those of prose and novels. The subjects of his work remained the same – he lived the life of the poor and the down-trodden, associating himself with drinking, drugs, music, violence, prostitution and gambling. According to Adam Kirsch, Bukowski described his own readership as “the defeated, the demented and the damned.” His first book of short stories was published in 1972 and entitled Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions, and General Tales of Ordinary Madness. In general, his works were often offensive, violent and sordid, but did a few amazing things… brought awareness to the lives of the down-and-out and opened up the literary world to an entirely different style of writing.

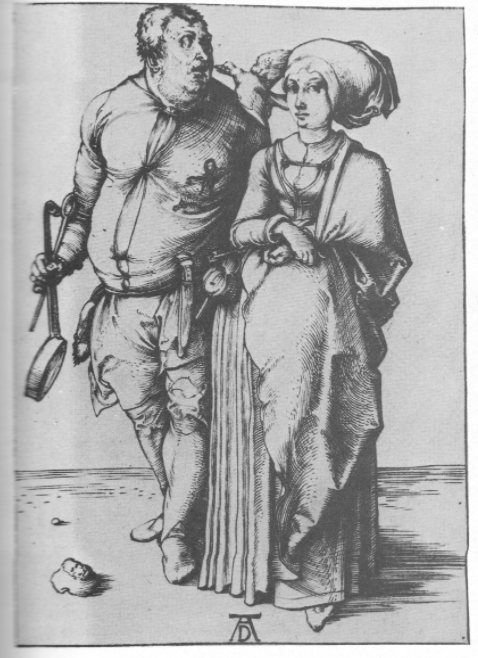

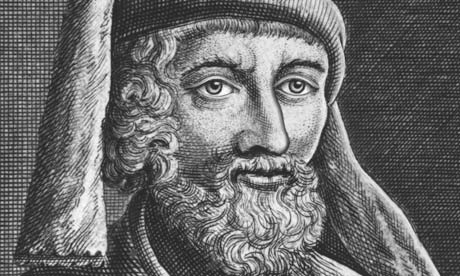

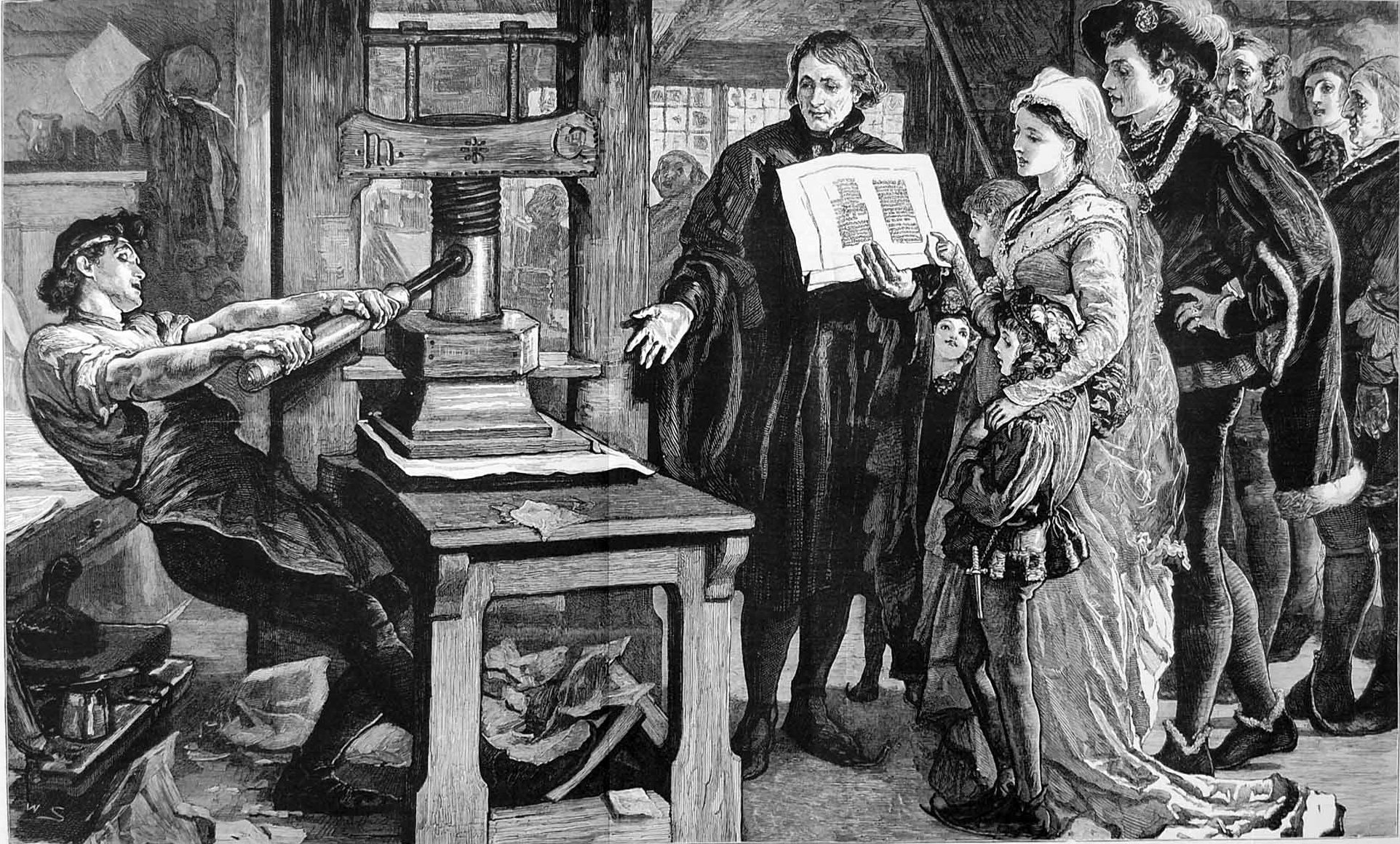

William Caxton was born sometime during the years 1415-1424, which scholars have appropriated since his apprenticeship fees were paid in 1438. He grew up and was educated in the district of Kent, before leaving for London to be apprentice to Robert Large, a wealthy London dealer or luxury goods. Caxton made trips to Bruge after the death of Large in 1441, and eventually settled there in 1453. He was successful in his business as a merchant, and after becoming governor of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London he became a member of the household of Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy and sister to two Kings of England! This was a fortuitous time in Caxton’s life, as due to his international travels for the Duchess’ household he observed the brand new printing press business in Germany (as the Gutenberg press had began in 1440) and immediately set up his own printing press in Bruge and within a few years produced the first book known to be printed in English, published in 1473 Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (“A Collection of the Histories of Troy” ) – a book of French courtly love translated by Caxton himself. (Fun antiquarian book world fact: only 18 copies of this printing still exist [kind of shocking there are even 18], and one sold by the Duke of Northumberland in 2014 and fetched over 1 million GBP.)

William Caxton was born sometime during the years 1415-1424, which scholars have appropriated since his apprenticeship fees were paid in 1438. He grew up and was educated in the district of Kent, before leaving for London to be apprentice to Robert Large, a wealthy London dealer or luxury goods. Caxton made trips to Bruge after the death of Large in 1441, and eventually settled there in 1453. He was successful in his business as a merchant, and after becoming governor of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London he became a member of the household of Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy and sister to two Kings of England! This was a fortuitous time in Caxton’s life, as due to his international travels for the Duchess’ household he observed the brand new printing press business in Germany (as the Gutenberg press had began in 1440) and immediately set up his own printing press in Bruge and within a few years produced the first book known to be printed in English, published in 1473 Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (“A Collection of the Histories of Troy” ) – a book of French courtly love translated by Caxton himself. (Fun antiquarian book world fact: only 18 copies of this printing still exist [kind of shocking there are even 18], and one sold by the Duke of Northumberland in 2014 and fetched over 1 million GBP.) After his success with the printing in Bruge, Caxton brought his art back to England in 1476 and set up the country’s first ever press in a section of the Westminster Abbey Church. The first book printed in England itself was an edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Other early titles printed by Caxton included Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres translated by the king’s brother in law Earl Rivers, and Caxton’s own translations of the Golden Legend in 1483 and The Book of the Knight in the Tower. Caxton also printed the first ever English translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, as well as Le Morte d’Arthur.

After his success with the printing in Bruge, Caxton brought his art back to England in 1476 and set up the country’s first ever press in a section of the Westminster Abbey Church. The first book printed in England itself was an edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Other early titles printed by Caxton included Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres translated by the king’s brother in law Earl Rivers, and Caxton’s own translations of the Golden Legend in 1483 and The Book of the Knight in the Tower. Caxton also printed the first ever English translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, as well as Le Morte d’Arthur. Caxton’s death is recognized as taking place in 1491 or 1492, as that is when his work stopped being produced. He was succeeded by his Dutch employee Wynkyn de Worde, who is recognized for moving the printing of books in English away from an excitement enjoyed by the aristocrazy and nobility and toward the idea of printing for the masses. De Worde is often known as “England’s first typographer” and printed over 400 books in over 800 editions. Caxton, god bless him, printed 108 books of 87 different titles. However, Caxton did much of his translating himself, working on an honest desire to provide the best translation possible to his customers. Despite the fact that de Worde is known for standardizing the English language (as there were, at that time, so many different dialects and different spellings that it was often difficult to keep track), Caxton is absolutely also honored for beginning this process and though printing books of no remarkable or significant beauty, then at least for beginning the process of printing books in English at all!

Caxton’s death is recognized as taking place in 1491 or 1492, as that is when his work stopped being produced. He was succeeded by his Dutch employee Wynkyn de Worde, who is recognized for moving the printing of books in English away from an excitement enjoyed by the aristocrazy and nobility and toward the idea of printing for the masses. De Worde is often known as “England’s first typographer” and printed over 400 books in over 800 editions. Caxton, god bless him, printed 108 books of 87 different titles. However, Caxton did much of his translating himself, working on an honest desire to provide the best translation possible to his customers. Despite the fact that de Worde is known for standardizing the English language (as there were, at that time, so many different dialects and different spellings that it was often difficult to keep track), Caxton is absolutely also honored for beginning this process and though printing books of no remarkable or significant beauty, then at least for beginning the process of printing books in English at all!