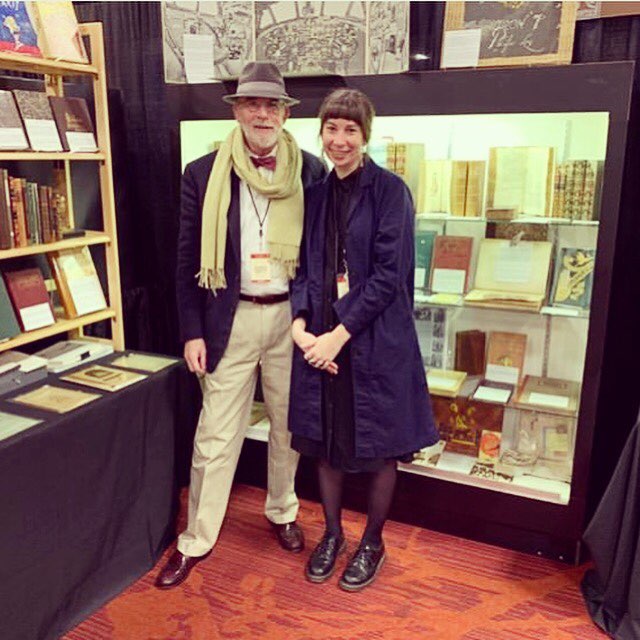

What were you most excited about for the Oakland ABAA fair?

Samm: Having everyone in town on our “turf” to invite to the shop and seeing all the international dealers!

Vic: The ending…? Seriously, it had been a long 10 days for us, what with the Pasadena fair the weekend prior, and boy, by the end of Sunday, my dogs were barkin’, let me tell you!

What was the theme of this year’s California ABAA fair and how did it present itself at the fair?

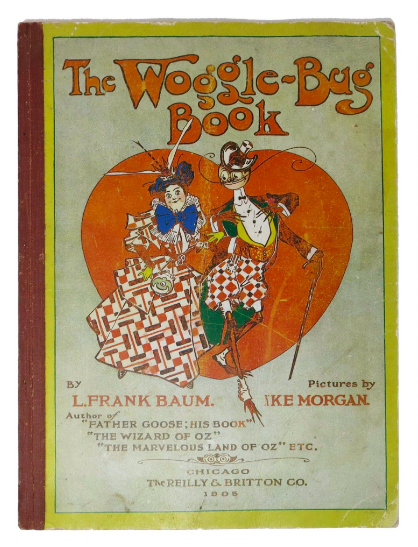

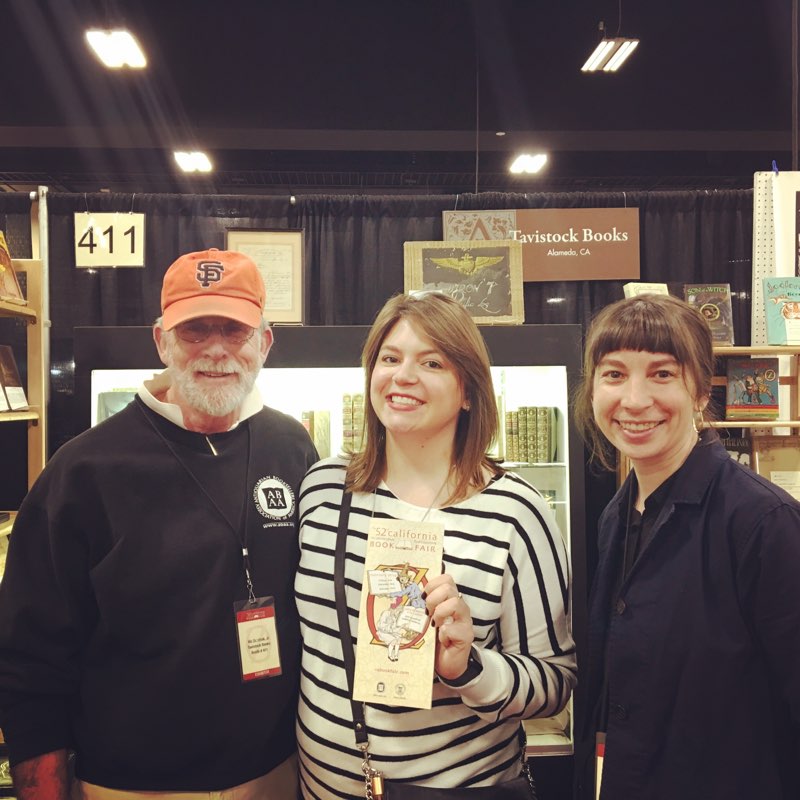

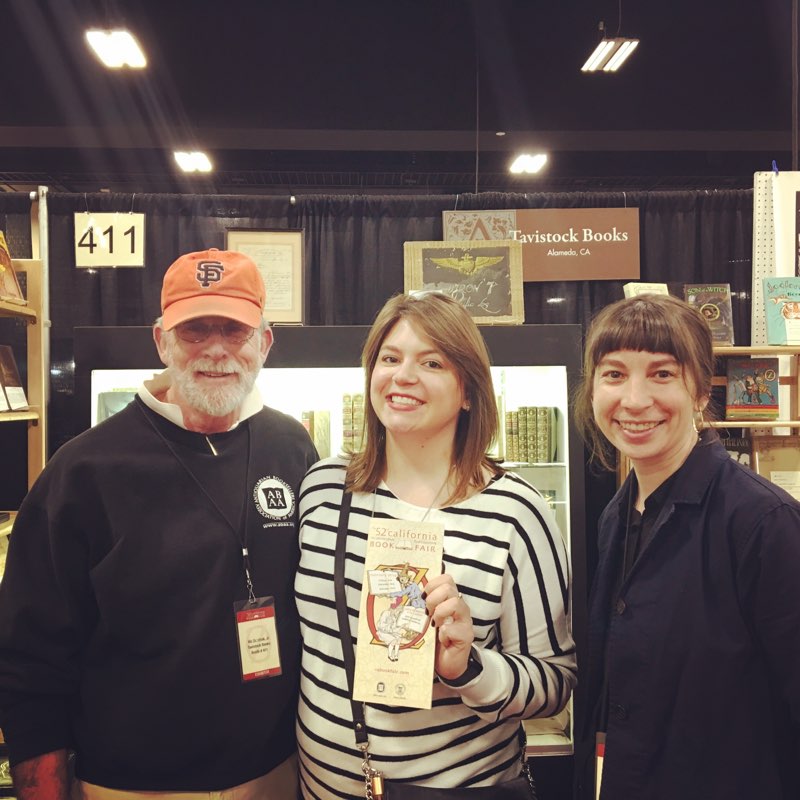

Samm: The theme of this years fair was OZ. There was a large collection of rare Oz items in the room. A lot of dealers also brought some things from their Oz collections that were dispersed around peoples booths… there was a touch of Oz or Baum almost everywhere if you looked hard enough!

Vic: The OZ theme was very well presented, though we’re sorry to say the OZ things we brought, we also brought back to the shop! But nevertheless, it was an exciting theme, and I saw some wonderful material in the genre throughout the room.

Were there any special events you two attended that you’d like to make note of for us?

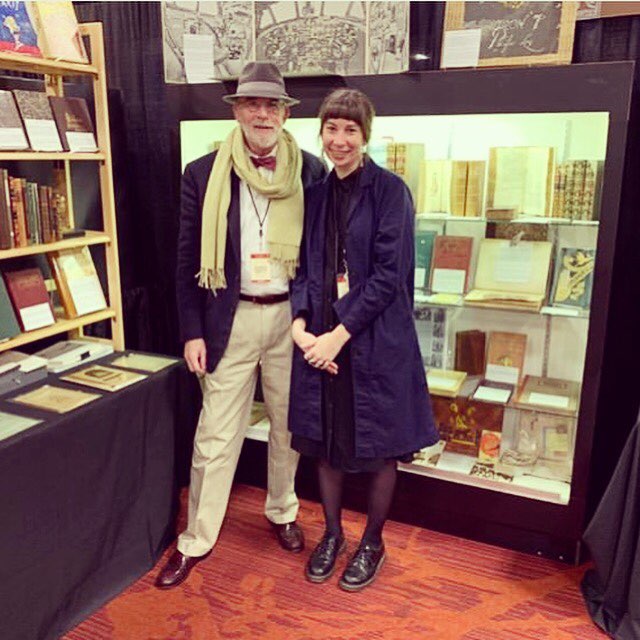

Samm: We did not make the poker benefit as we were exhausted. I personally did not make the talk put on by the Womens Initiative as I was finally taking time to browse the booths. I snuck in for a brief minute to see Vic’s talk and take some photos. He had a large turn out and looked super comfortable up on stage. Some people who attended his seminar even came and browsed the booth and told him that they very much enjoyed his talk.

Vic: One that perhaps deserved more press I’d like to mention here: the Northern California Chapter’s “Young Book Collector’s Prize.” The award was won by a nice young man from La Jolla, Matthew Wills. His collection, “Anti-Confucian Propaganda in Mao’s China”, was on display in the room. This award, and the many young people who submitted entries, indicates to me that book collecting is alive & well with the next generation.

Vic, did you speak at this year’s fair?

Samm: He did! “Whats a Book Worth?” and “Book Collecting 101” were his two seminars.

Vic: Samm’s right, I did, though it was my ’Swan’ song so to speak, as Laurelle Swan, Swan’s Fine Books, will take over for me come 2021. Yes, pun intended! 🙂

How was the attendance at the Oakland fair?

Samm: The turn out was the best on Saturday I think. The rain was a bit lighter. Friday was a dreary day, but people still came out. Overall, a good turn out I thought, but I don’t have another ABAA fair to compare too!

Vic: Both were of modest proportions for us in Oakland, though I thought the promoter did well getting people through the door. But we had few sales to the general public, so, for whatever reason, the material we brought failed to resonate with them. You win some, you lose some.

Which fair was better overall for Tavistock Books – the Oakland fair or Pasadena fair – in terms of buying, selling and fun?

Samm: In terms of buying I would say Pasadena. In terms of selling and fun I would say Oakland. The fun and selling go hand in hand I think as we had our “Shin-dig” which was great and we sold some items at that too!

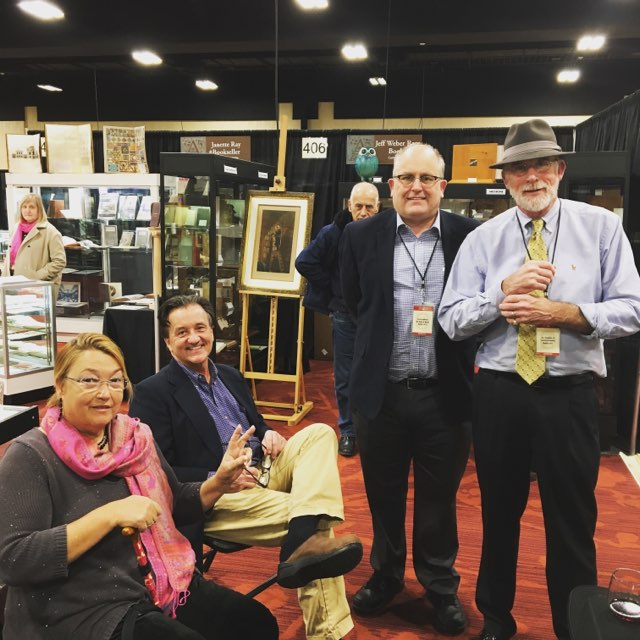

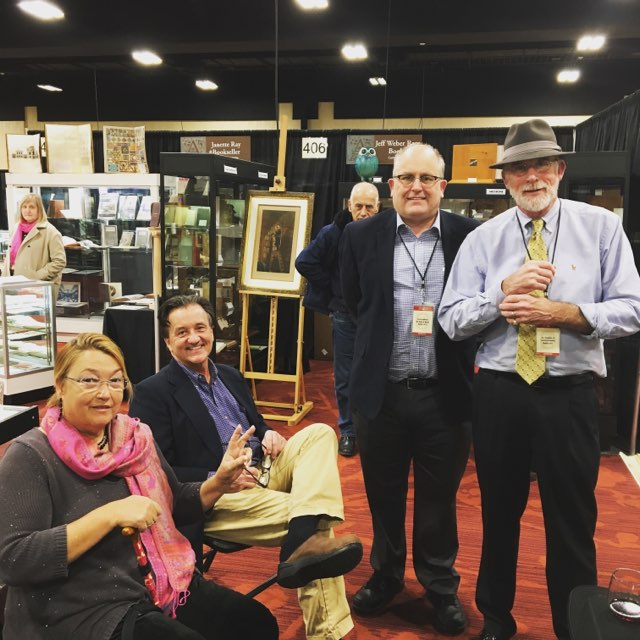

Vic: This a tough call… our energy levels were higher in Pasadena, and I didn’t have ABAA responsibilities while in Pasadena [in Oakland, I had a Board of Governors meeting, as well as the Association’s Annual meeting]. That said, it’s always a pleasure to see colleagues, and perhaps share a meal. While in Oakland, groups of us did get out to both Wood Tavern & Chez Panisse, two of the top East Bay restaurants. And yes, Samm is correct, we bought way more in Pasadena [for details, watch our forthcoming Wednesday morning lists!].

Is the Oakland fair still as much of a draw as it has been since the year they moved it from San Francisco?

Vic: Here in California, to be honest, our biggest attendance detriment is the proximity of the New York book fair [early March]. The ABAA leadership is acutely aware of this situation, and hopes, in future years, to introduce more of a calendar separation between the two events.

How did your pre-fair Tavistock Books shindig go?

Vic: Given it’s last minute nature, we think it went well! We did have a number of colleagues say they’d already had commitments, and therefore weren’t able to make it. Samm & I agreed to do it again in 2021, and ‘get the word out’ much earlier that year.

Samm: It was fun! We had a good turn out – maybe 15 people or so filtering in and out! Sold some items! People drank our drinks and ate snacks and talked books! What could be better?

What did you both learn at this year’s fair that you might not have known before it?

Samm: I suppose I learned that you can never truly know what will sell. You don’t know what booksellers will want, which collectors will be there etc. It can be a guessing game. But having a website to shop and storefront helps. So you may not make a sale at the fair itself but you can offer those other options to make a sale at a later date!

Vic: I’ve done enough of these fairs over the last 30 years that the one thing I’ve learned is that no one fair is like any other! It’s like rolling dice, you just hope a 7 comes up.

And last but not least… Vic, what is different about being president of the ABAA at an ABAA fair?

Vic: Interesting question Ms P, for this is the first ABAA fair at which I’ve exhibited since becoming the Association’s President. What I found is that knowing I’m the President, ABAA colleagues came over to chat about diver Association matters, which is a good thing. To properly do my job as President, I need to know how members stand on different issues. For those that took the time to do so, I thank you.

And that’s a wrap, ladies and gentlemen!

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at The New York Times. Less than a year later, unfortunately, Carle was drafted once more into war, and America sent the recent civilian to the Korean War, where he was stationed back in Germany until discharged a year later at the end of the war. After returning to New York, Carle once more took up his job at The New York Times for a time, before becoming the art director for an advertising agency in the city.

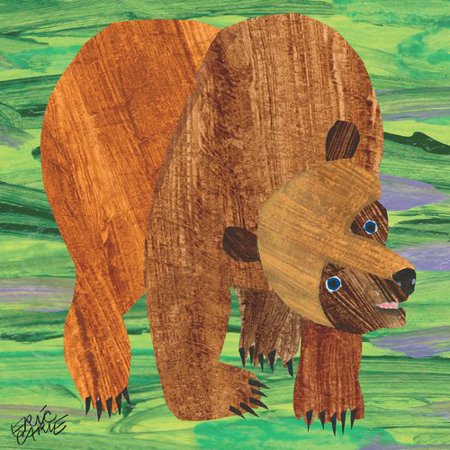

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at The New York Times. Less than a year later, unfortunately, Carle was drafted once more into war, and America sent the recent civilian to the Korean War, where he was stationed back in Germany until discharged a year later at the end of the war. After returning to New York, Carle once more took up his job at The New York Times for a time, before becoming the art director for an advertising agency in the city.  It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.

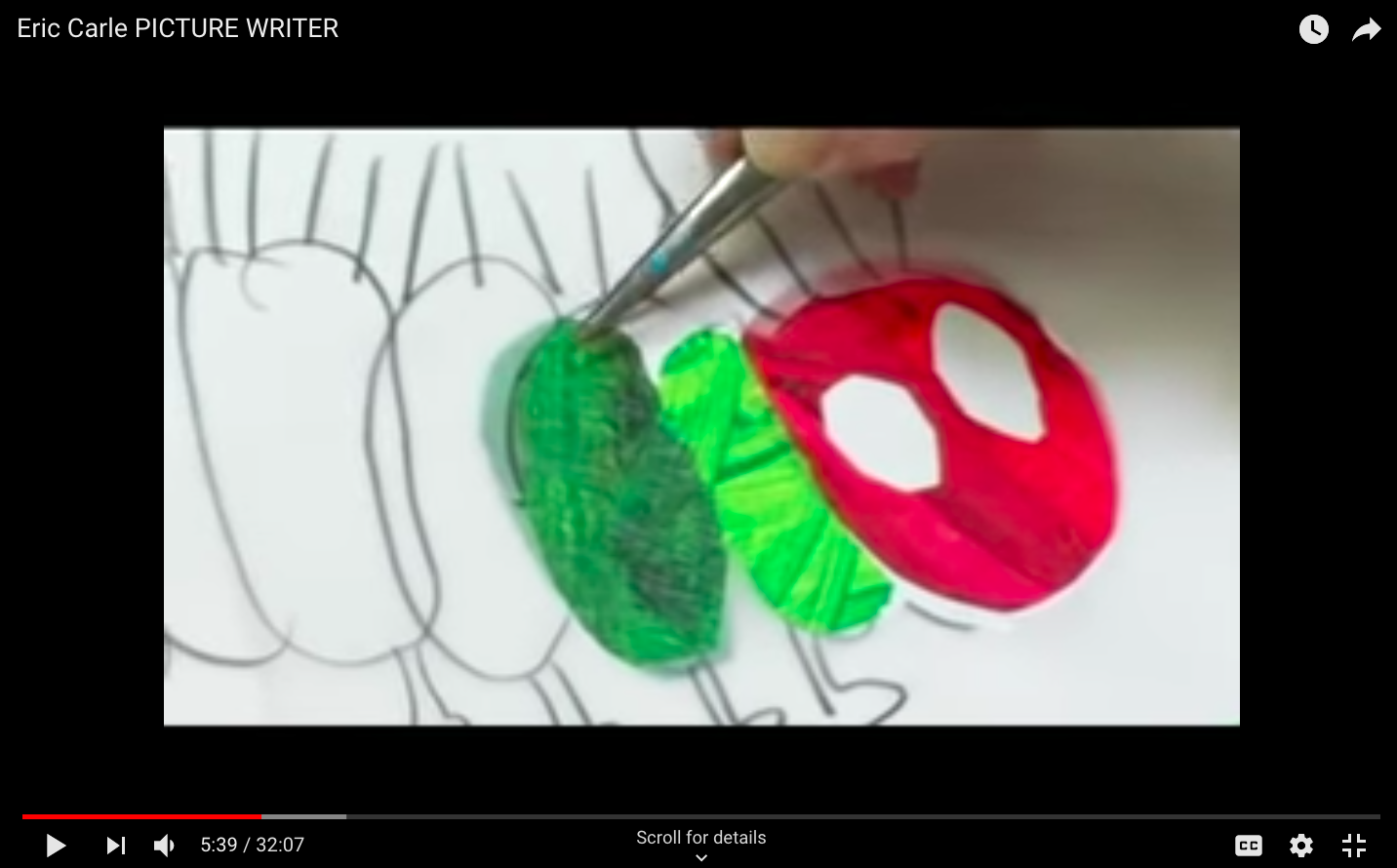

It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own. One reason behind the popularity of Carle’s work is that his illustrations are so very unique. He creates collages using hand-painted paper, which he then cuts to shape and layers to create the right colors and designs. A 30-minute video of Carle’s work, both in his design, and the way he carries out his ideas, and his work with his wife and children around the world can be seen here! This video, “The Art of Picture Books. Illustrating, story telling and making meaning with children” might be an older documentary, but we cannot recommend it enough to give our readers an overview of this famous artist and the beautiful, captivating and distinctive exceptional works that he has given to children throughout the years.

One reason behind the popularity of Carle’s work is that his illustrations are so very unique. He creates collages using hand-painted paper, which he then cuts to shape and layers to create the right colors and designs. A 30-minute video of Carle’s work, both in his design, and the way he carries out his ideas, and his work with his wife and children around the world can be seen here! This video, “The Art of Picture Books. Illustrating, story telling and making meaning with children” might be an older documentary, but we cannot recommend it enough to give our readers an overview of this famous artist and the beautiful, captivating and distinctive exceptional works that he has given to children throughout the years.

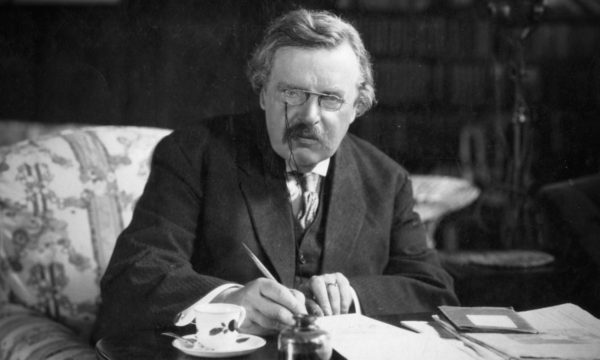

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born on May 29th, 1874, in Kensington, London. His childhood is not elaborately researched, but we do know that he was born to a family of Unitarians, and as a young man was interested in the occult and regularly played (or practiced) with a Quija board with his younger brother (and only sibling) Cecil. He was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, but instead of continuing on to a university as you might have expected, Chesterton attended the Slade School of Art in London – in hopes of eventually becoming an illustrator. Though at Slade Chesterton took lessons in both art and literature, Chesterton left without a degree in either!

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born on May 29th, 1874, in Kensington, London. His childhood is not elaborately researched, but we do know that he was born to a family of Unitarians, and as a young man was interested in the occult and regularly played (or practiced) with a Quija board with his younger brother (and only sibling) Cecil. He was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, but instead of continuing on to a university as you might have expected, Chesterton attended the Slade School of Art in London – in hopes of eventually becoming an illustrator. Though at Slade Chesterton took lessons in both art and literature, Chesterton left without a degree in either! When Chesterton was 27 years old, he married Frances Alice Blogg – an author herself, who would prove to be a major influence on Chesterton’s writing and religious life throughout the years. As www.chesterton.org mentions, Frances was in charge of all aspects of Chesterton’s life – kept his schedule for him, kept house, and kept him in check. According to the site, Chesterton often “had no idea where or when his next appointment was. He did much of his writing in train stations, since he usually missed the train he was supposed to catch. In one famous anecdote, he wired his wife, saying, ‘Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?’” To which Mrs. Chesterton would almost inevitably respond with “Home.” The Chesterton’s were perhaps the epitome of the phrase “Behind every great man is an even greater woman.”

When Chesterton was 27 years old, he married Frances Alice Blogg – an author herself, who would prove to be a major influence on Chesterton’s writing and religious life throughout the years. As www.chesterton.org mentions, Frances was in charge of all aspects of Chesterton’s life – kept his schedule for him, kept house, and kept him in check. According to the site, Chesterton often “had no idea where or when his next appointment was. He did much of his writing in train stations, since he usually missed the train he was supposed to catch. In one famous anecdote, he wired his wife, saying, ‘Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?’” To which Mrs. Chesterton would almost inevitably respond with “Home.” The Chesterton’s were perhaps the epitome of the phrase “Behind every great man is an even greater woman.”

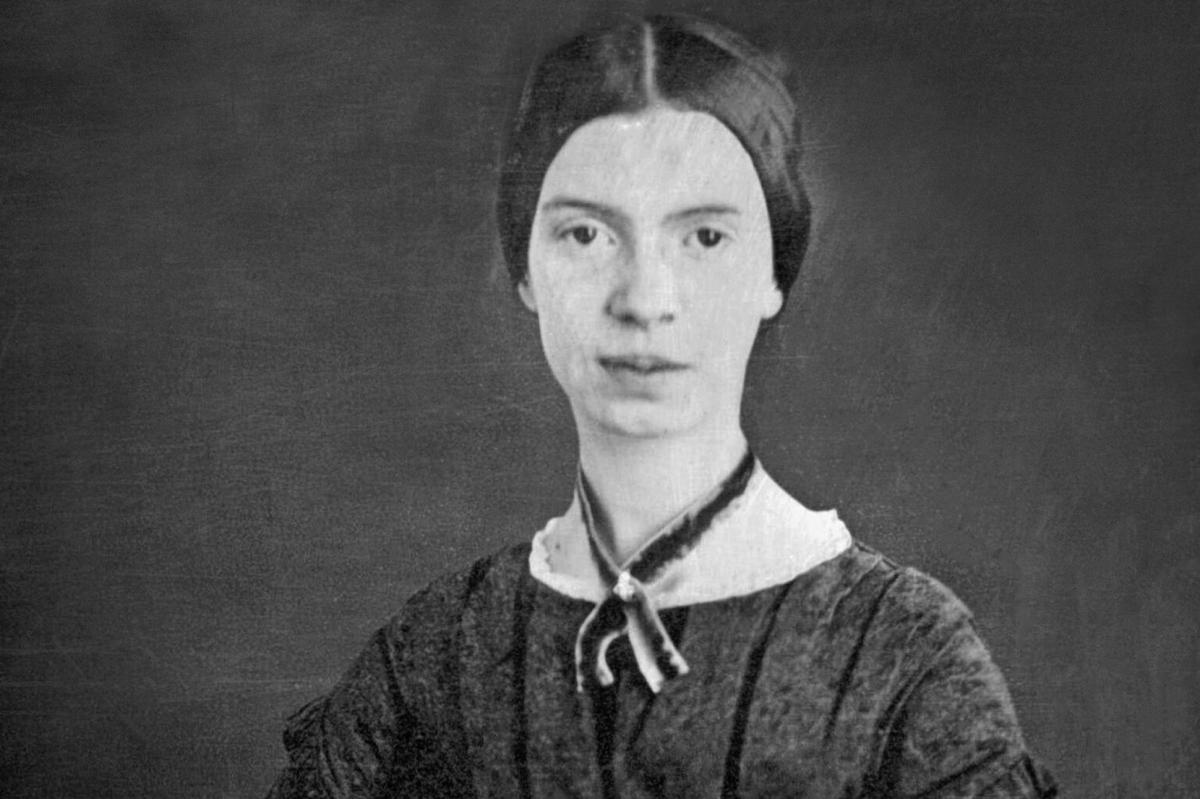

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of. Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

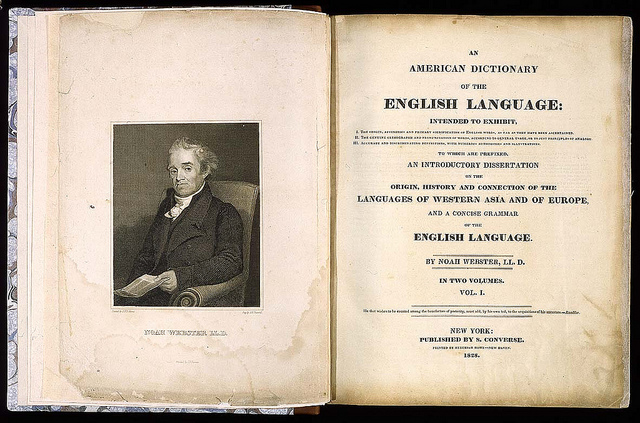

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.