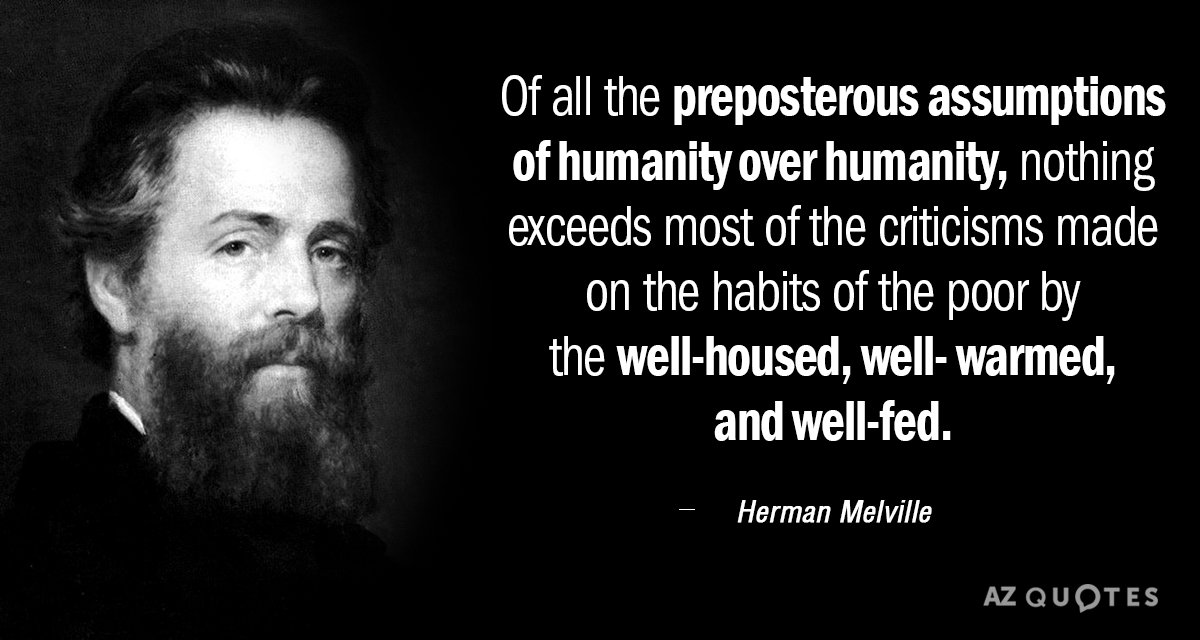

Moby-Dick is, undeniably, a classic American novel. But did you know that at the time of its publication it was considered a total flop? In fact, Melville’s prior novels (which some of you may never have even heard of) did much, much better in American critical literary society than Moby-Dick. Readers could not see past the complexity of the novel – they were expecting an adventure tale and what they got was “obscure literary symbolism.” I always find it humorous (though I am sure it wasn’t humorous to Melville) when a work that is today considered of the highest class was at the time frowned upon. The old Picasso problem, right? At least due to these instances we understand what genius looks like at the beginning, no?

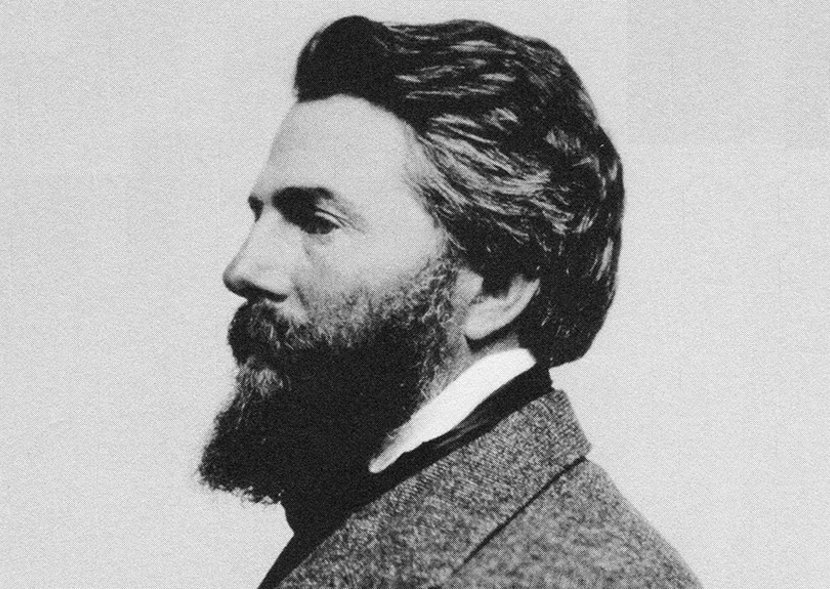

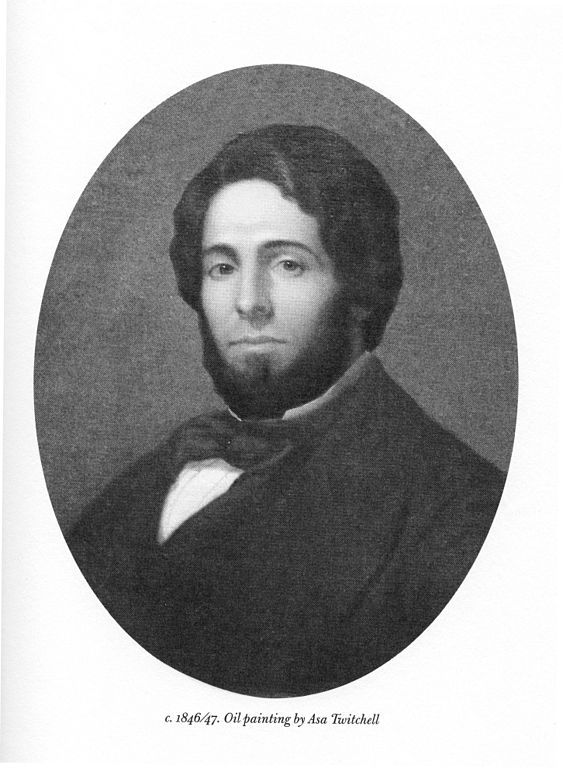

Herman Melvill (yes, that spelling is correct) was born in August of 1819 in New York City. He was the third of eight children born to a merchant and his wife. Though his parents have been described as loving and devoted, his father Allan’s money woes left much to be desired. Allan borrowed and spent well beyond his means, and after contracting what researchers imagine as pneumonia on a trip back to Albany from New York City, he abruptly passed away when Herman was merely 13 years old. Herman’s schooling ended as abruptly as his father’s life, and he was given a job as a clerk in the fur trade (his father’s business) by his uncle. Sometime around this time, Herman’s mother changed the spelling of their last name by adding an “e” to the end. History is still unsure as to why she would have done this – to sound more sophisticated, to hide from debt collectors… we may never know! But that simple “e” will live on forever, that is for sure.

Herman Melvill (yes, that spelling is correct) was born in August of 1819 in New York City. He was the third of eight children born to a merchant and his wife. Though his parents have been described as loving and devoted, his father Allan’s money woes left much to be desired. Allan borrowed and spent well beyond his means, and after contracting what researchers imagine as pneumonia on a trip back to Albany from New York City, he abruptly passed away when Herman was merely 13 years old. Herman’s schooling ended as abruptly as his father’s life, and he was given a job as a clerk in the fur trade (his father’s business) by his uncle. Sometime around this time, Herman’s mother changed the spelling of their last name by adding an “e” to the end. History is still unsure as to why she would have done this – to sound more sophisticated, to hide from debt collectors… we may never know! But that simple “e” will live on forever, that is for sure.

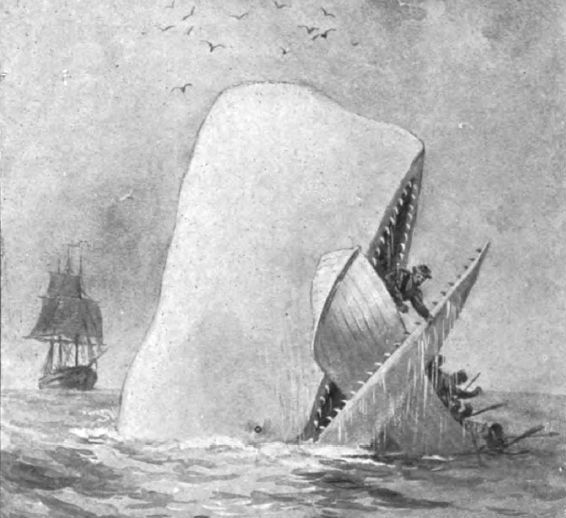

In May of 1831 Melville signed up as a “boy” (a newbie, for all intents and purposes) on a merchant ship called the St. Lawrence, and went from New York to Liverpool and back. That experience successful (and what with a longstanding obsession with the true story of the search for the white sperm whale called Mocha Dick), he decided to join the Acushnet for a whaling voyage in 1841. After a few months on board, Melville decided to jump ship with another deckhand in the Marquesas Islands after several reported disagreements with the captain of the ship. Expecting to come across cannibalistic natives, Melville was (unsurprisingly) pleased to find out that the natives were accommodating and friendly – a fact which he would later address in his 1845 novel Typee – semi-autobiographical in nature as it was based on his stay in the islands. Melville then experienced island and country hopping to an extreme degree, after boarding a boat from the Marquesas to Australia then continuing on whaling and merchant vessels visiting Tahiti, Oahu, Rio de Janeiro and Lima, Peru – among others. Eventually, Melville ended up back in Boston, Massachusetts.

In May of 1831 Melville signed up as a “boy” (a newbie, for all intents and purposes) on a merchant ship called the St. Lawrence, and went from New York to Liverpool and back. That experience successful (and what with a longstanding obsession with the true story of the search for the white sperm whale called Mocha Dick), he decided to join the Acushnet for a whaling voyage in 1841. After a few months on board, Melville decided to jump ship with another deckhand in the Marquesas Islands after several reported disagreements with the captain of the ship. Expecting to come across cannibalistic natives, Melville was (unsurprisingly) pleased to find out that the natives were accommodating and friendly – a fact which he would later address in his 1845 novel Typee – semi-autobiographical in nature as it was based on his stay in the islands. Melville then experienced island and country hopping to an extreme degree, after boarding a boat from the Marquesas to Australia then continuing on whaling and merchant vessels visiting Tahiti, Oahu, Rio de Janeiro and Lima, Peru – among others. Eventually, Melville ended up back in Boston, Massachusetts.

Between the years 1845 and 1850, Melville experienced substantial success as a writer. His first novel Typee performed well in both public and critical arenas, and its sequel Omoo (also based on his time in the islands) performed almost equally as well. During these years Melville won the hand of Elizabeth Shaw in marriage, which throughout the years would give him four children – two sons and two daughters (though only the daughters would live to adulthood). Melville followed Omoo with novels Redburn and White-Jacket – both successful enough in their own right to afford Melville the opportunity to buy his beloved home Arrowhead in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which was an inspirational setting for his writing. It was here that he wrote Moby-Dick, or The Whale – which started as a simpler story on a fictional whaling event and eventually (with the aid of Melville’s friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who had recently enjoyed success with his novel The Scarlet Letter) turned into the allegorical novel it came to be. As a matter of fact, Melville dedicated what is now considered his most enduring work but became the flop that threatened to break his bank account to this friend and colleague.

After the unfortunate reception of Moby-Dick – it seemed a bit too far-fetched in style and meaning for its audience – Melville was forced to sell his home in Pittsfield to his brother and move his family back to New York City, where he took up work as a district inspector for the U.S. Customs Service. Though his writing took much of a backseat at this time (roughly 1857 to the late 1870s), Melville continued to write poetry throughout his lifetime, up until his death from cardiac arrest on September 28th, 1891, when he was 72 years old. His last work Billy Budd he had stopped working on in 1888, but was found accidentally and published posthumously in 1891 – and today holds great esteem as yet another wonderful work by a misunderstood great American novelist. Today, 127 years to the day of Melville’s death, we are glad to have a chance to study and appreciate his work today. And if you haven’t yet read Typee – we greatly recommend it!

Bradbury was born on August 22nd, 1920, in rural Illinois. In 1932 at the age of twelve, Bradbury had a somewhat extraordinary experience with a traveling magician known as Mr. Electrico – who touched him on the nose and exclaimed “live forever!” – to which Bradbury took in the best way possible – his literature (which he began writing only days after this experience) will live forever. A couple short years later, the Bradbury family relocated to Los Angeles, where he was able to join the Los Angeles Science Fiction league as a teenager, and counted authors such as Robert Heinlein and Henry Kuttner among his mentors.

Bradbury was born on August 22nd, 1920, in rural Illinois. In 1932 at the age of twelve, Bradbury had a somewhat extraordinary experience with a traveling magician known as Mr. Electrico – who touched him on the nose and exclaimed “live forever!” – to which Bradbury took in the best way possible – his literature (which he began writing only days after this experience) will live forever. A couple short years later, the Bradbury family relocated to Los Angeles, where he was able to join the Los Angeles Science Fiction league as a teenager, and counted authors such as Robert Heinlein and Henry Kuttner among his mentors.

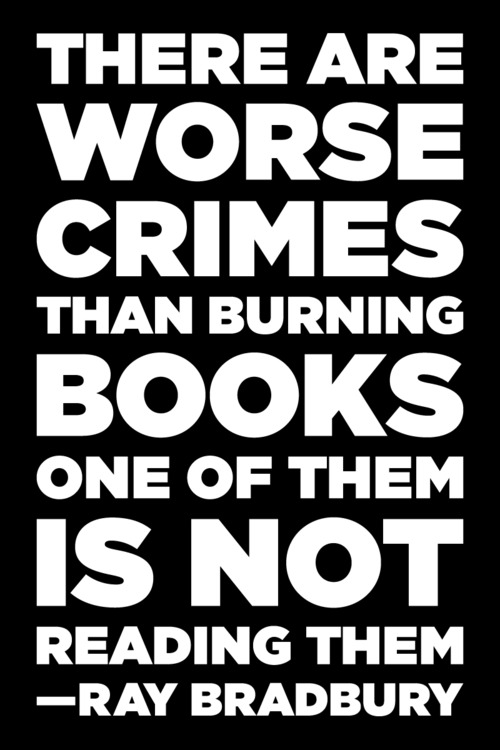

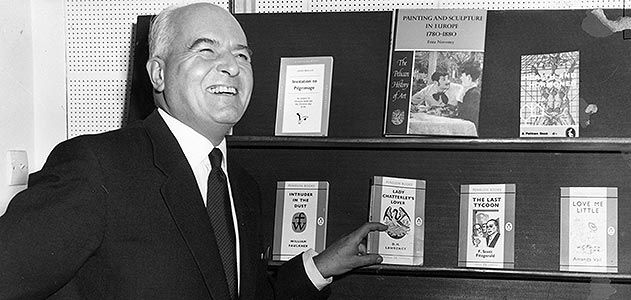

At the age of 19 his literary career began getting even more serious – and he honed with fantastical science fiction writing style by publishing his own fanzine, called Futuria Fantasia, and traveling to the first World Science Fiction convention, held in 1939 in New York City. His short stories began to be published in Science Fiction magazines such as Weird Tales and Super Science Stories. In the 1940s, Bradbury began to be published in high-end literary and social magazines like Harper’s, the American Mercury, Collier’s and The New Yorker – not typical for most science fiction writers. And to do it without losing sight of your style and genre – almost unheard of! Bradbury published short stories, series’, and novels over the coming years. In 1953 his novel Fahrenheit 451 hit the shelves – and is now regarded as one of his greatest works. It follows a futuristic world where censorship is in full force and follows the seduction of one firefighter through the world of literature. Fahrenheit 451 was closely followed by his collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, where the story inspiration for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was found. He followed up his works with more and more short stories, and more novels, until his later life, when he elected to turn more often towards poetry, drama and mysteries – including adapting his stories for the big screen. Despite being considered a primarily science fiction writer, Bradbury often considered his works more in the fantasy, horror and mystery genres – that he did not stay true to science fiction themes, with the exception of his novel Fahrenheit 451.

At the age of 19 his literary career began getting even more serious – and he honed with fantastical science fiction writing style by publishing his own fanzine, called Futuria Fantasia, and traveling to the first World Science Fiction convention, held in 1939 in New York City. His short stories began to be published in Science Fiction magazines such as Weird Tales and Super Science Stories. In the 1940s, Bradbury began to be published in high-end literary and social magazines like Harper’s, the American Mercury, Collier’s and The New Yorker – not typical for most science fiction writers. And to do it without losing sight of your style and genre – almost unheard of! Bradbury published short stories, series’, and novels over the coming years. In 1953 his novel Fahrenheit 451 hit the shelves – and is now regarded as one of his greatest works. It follows a futuristic world where censorship is in full force and follows the seduction of one firefighter through the world of literature. Fahrenheit 451 was closely followed by his collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, where the story inspiration for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was found. He followed up his works with more and more short stories, and more novels, until his later life, when he elected to turn more often towards poetry, drama and mysteries – including adapting his stories for the big screen. Despite being considered a primarily science fiction writer, Bradbury often considered his works more in the fantasy, horror and mystery genres – that he did not stay true to science fiction themes, with the exception of his novel Fahrenheit 451.

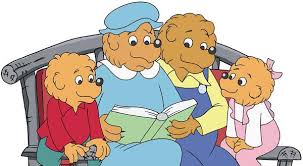

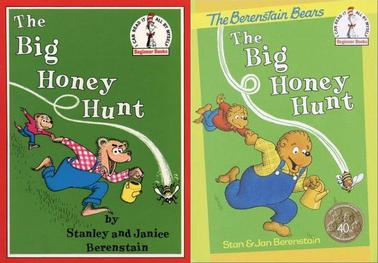

In 1941, Janice Grant and Stanley Berenstain met on their first day at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and became close very quickly. At the onset of World War II, they took up different war effort posts (as a medical illustrator and riveter), but were eventually reunited and married in 1946. They found work as art teachers, then eventually became co-illustrators, publishing works like the Berenstain’s Baby Book in 1951 followed by many more (including, but not limited to Marital Blitz, How To Teach Your Children About Sex Without Making A Complete Fool of Yourself and Have A Baby, My Wife Just Had A Cigar). In the early 1960s the Berentain’s first “Berenstain Bears” book made it to a very important colleague and publisher – Theodore Geisel – or, as some of you may remember from our somewhat recent blog, Dr. Seuss!

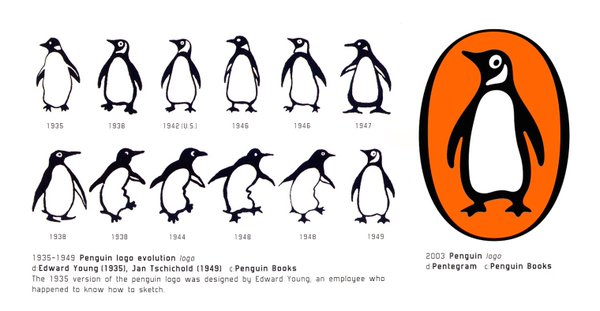

In 1941, Janice Grant and Stanley Berenstain met on their first day at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and became close very quickly. At the onset of World War II, they took up different war effort posts (as a medical illustrator and riveter), but were eventually reunited and married in 1946. They found work as art teachers, then eventually became co-illustrators, publishing works like the Berenstain’s Baby Book in 1951 followed by many more (including, but not limited to Marital Blitz, How To Teach Your Children About Sex Without Making A Complete Fool of Yourself and Have A Baby, My Wife Just Had A Cigar). In the early 1960s the Berentain’s first “Berenstain Bears” book made it to a very important colleague and publisher – Theodore Geisel – or, as some of you may remember from our somewhat recent blog, Dr. Seuss! Geisel traded ideas with the Berenstains for over a year – until he finally felt like they had a marketable product for the American public. In 1962, The Big Honey Hunt hit shelves across the USA. The Berenstains were working on their next book – featuring penguins – when Geisel got in touch to say another bear book was needed by demand, as The Big Honey Hunt was selling so undeniably well. Two years later The Bike Lesson came out… which began a waterfall of publications… at least one a year since then, but typically more than a few. A record 25 Berenstain Bears books were published in 1993 alone! Six titles have already been published in 2018. The immediate success of the Berenstain Bears lead to a situation not unlike the popular Hardy Boys series or Nancy Drew’s popularity – only for a younger age range and with a somewhat different tone. Not to mention all written and illustrated by the same authors, at least until Mike Berenstain took over the franchise in 2002. Jan and Stan were quite a busy pair for a number of years!

Geisel traded ideas with the Berenstains for over a year – until he finally felt like they had a marketable product for the American public. In 1962, The Big Honey Hunt hit shelves across the USA. The Berenstains were working on their next book – featuring penguins – when Geisel got in touch to say another bear book was needed by demand, as The Big Honey Hunt was selling so undeniably well. Two years later The Bike Lesson came out… which began a waterfall of publications… at least one a year since then, but typically more than a few. A record 25 Berenstain Bears books were published in 1993 alone! Six titles have already been published in 2018. The immediate success of the Berenstain Bears lead to a situation not unlike the popular Hardy Boys series or Nancy Drew’s popularity – only for a younger age range and with a somewhat different tone. Not to mention all written and illustrated by the same authors, at least until Mike Berenstain took over the franchise in 2002. Jan and Stan were quite a busy pair for a number of years!

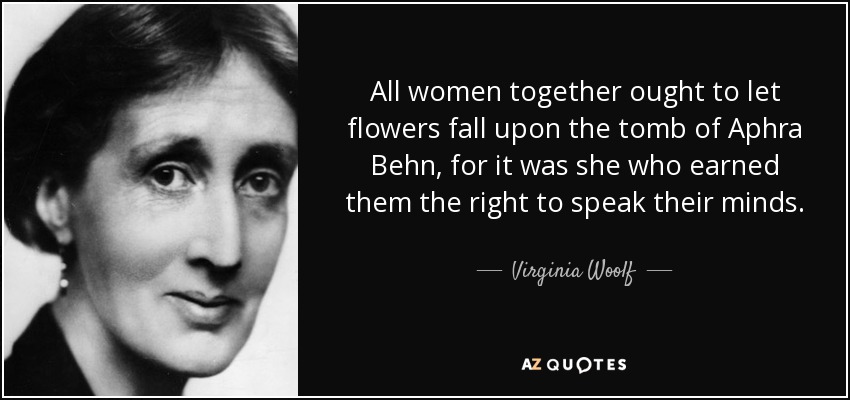

As a stout Stuart supporter, Behn became attached to the royal court after King Charles II came back into power in 1660. Now we get into the exciting (and more traceable) details of this woman’s life – in 1666 her connections to the crown landed her a job as a spy during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and she arrived in the Netherlands in July of that year. However, her time there did not pan out as planned, as Charles II was extremely neglectful of payments – and Behn was forced to return to England after having to pawn some of her jewelry in order to live abroad. After her return to England, she began working as a playwright (though reportedly had written poetry prior to this job) for the King’s and Duke’s Companies in London. Her work as a scribe was popular, and her plays began to be seen on the stage in 1670

As a stout Stuart supporter, Behn became attached to the royal court after King Charles II came back into power in 1660. Now we get into the exciting (and more traceable) details of this woman’s life – in 1666 her connections to the crown landed her a job as a spy during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and she arrived in the Netherlands in July of that year. However, her time there did not pan out as planned, as Charles II was extremely neglectful of payments – and Behn was forced to return to England after having to pawn some of her jewelry in order to live abroad. After her return to England, she began working as a playwright (though reportedly had written poetry prior to this job) for the King’s and Duke’s Companies in London. Her work as a scribe was popular, and her plays began to be seen on the stage in 1670

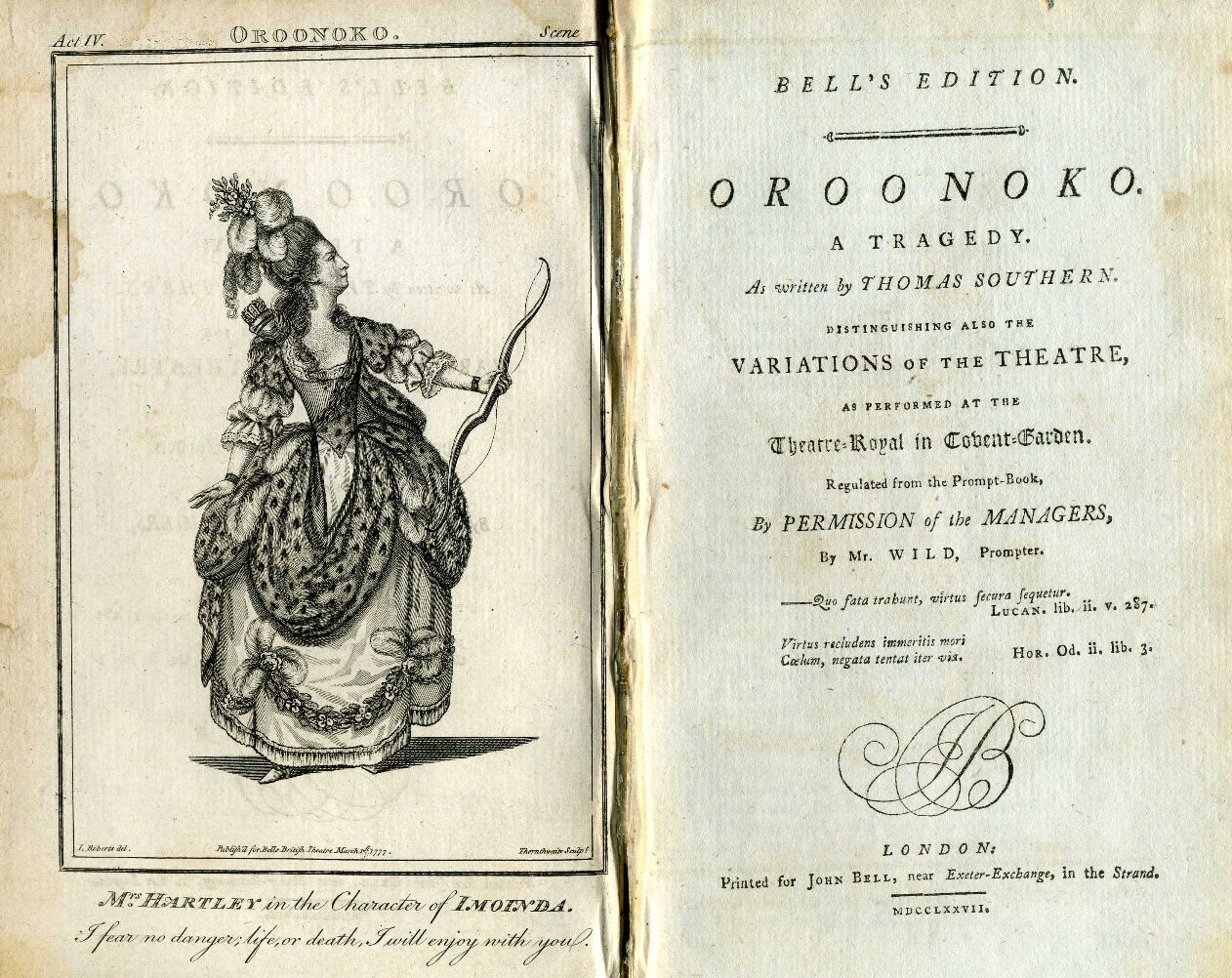

Publishing her famous novel Oroonoko just a year before her death in 1688, Behn truly wrote until her health completely deteriorated. Though she died at age 48 in relative poverty, Behn was buried in Westminster Abbey under her tombstone which reads, “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” (Hilarious even in death…) Happy Birthday to this early feminist!

Publishing her famous novel Oroonoko just a year before her death in 1688, Behn truly wrote until her health completely deteriorated. Though she died at age 48 in relative poverty, Behn was buried in Westminster Abbey under her tombstone which reads, “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” (Hilarious even in death…) Happy Birthday to this early feminist!

Barrie wrote several successful plays (and a couple flukes), but his third script brought him into contact with a young actress of the day – Mary Ansell – who would later, in 1894, become Barrie’s wife. For their union Barrie gifted Mary a St. Bernard puppy – who would become the inspiration for “Nana” in later years. They settled in London but kept a country home in Farnham, Surrey. In 1897 Barrie became acquainted with a nearby family – the Llewelyn Davies family.

Barrie wrote several successful plays (and a couple flukes), but his third script brought him into contact with a young actress of the day – Mary Ansell – who would later, in 1894, become Barrie’s wife. For their union Barrie gifted Mary a St. Bernard puppy – who would become the inspiration for “Nana” in later years. They settled in London but kept a country home in Farnham, Surrey. In 1897 Barrie became acquainted with a nearby family – the Llewelyn Davies family. Inspired largely by the stories he told to the Llewelyn Davies family, Barrie began to formulate a story of a boy who wouldn’t grow up, who flew around and had adventures. Not unlike Charles Dodgson’s Alice a century before, Barrie began to write his story into a play and once debuted in 1904, the play Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was an immediate success. George Bernard Shaw said of the performance, “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children, but really a play for grown-up people” – a wonderful description of the meanings and metaphors found in Peter Pan. Though children may see the adventure story on the outside, the adults in the audience could see what was really at play (pun intended) – Barrie’s social commentary on the adult’s fear of time and growing old and losing their childish innocence and fun, to name just a few.

Inspired largely by the stories he told to the Llewelyn Davies family, Barrie began to formulate a story of a boy who wouldn’t grow up, who flew around and had adventures. Not unlike Charles Dodgson’s Alice a century before, Barrie began to write his story into a play and once debuted in 1904, the play Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was an immediate success. George Bernard Shaw said of the performance, “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children, but really a play for grown-up people” – a wonderful description of the meanings and metaphors found in Peter Pan. Though children may see the adventure story on the outside, the adults in the audience could see what was really at play (pun intended) – Barrie’s social commentary on the adult’s fear of time and growing old and losing their childish innocence and fun, to name just a few.

However, Márquez’s passion lay in writing, despite continuing his law studies in order to please his father. That did not stop him from publishing his work, however. Having published poems throughout high school in his school journals and papers, La tercera resignación was his first published work as an adult, which appeared in the 13th of September, 1947 edition of the newspaper El Espectador. Coincidentally and luckily for Márquez,the assassination of Gaitán, in 1948 led his school to be closed indefinitely. Márquez began working as a reporter at El Universal and eventually moved on to write for El Heraldo.

However, Márquez’s passion lay in writing, despite continuing his law studies in order to please his father. That did not stop him from publishing his work, however. Having published poems throughout high school in his school journals and papers, La tercera resignación was his first published work as an adult, which appeared in the 13th of September, 1947 edition of the newspaper El Espectador. Coincidentally and luckily for Márquez,the assassination of Gaitán, in 1948 led his school to be closed indefinitely. Márquez began working as a reporter at El Universal and eventually moved on to write for El Heraldo.