Todays blog celebrates one of the many authors that we know the name of but few facts about. Despite a family wealth in the slave trade she was an abolitionist, she was a major supporter of child labor rights… and the first in her English-descended family to be born in the United Kingdom in over 200 years. Today’s blog honors one Elizabeth Barrett (later Elizabeth Barrett Browning)… poet, lover and worldwide literary influencer.

Elizabeth Barrett was born on March 6th, 1806 in Durham, England. As the first Barrett to be born outside of Jamaica since 1655, her birth was the cause for much celebration. Her family’s wealth had come from sugar plantations in the island country, meaning that her family did benefit from slave labour in running their grand plantations. Elizabeth was the eldest of twelve children, all but one of which would live to adulthood. Elizabeth’s childhood was fairly sweet and standard – full of family picnics, home theatricals and pony rides. However, unlike some other children (and definitely little girls) of the time, Elizabeth fixated on books and began writing, even as a four year old child. She was intensely studious, learning the Greek language by the age of ten and writing her own Homeric epic poem by eleven. Since both of her parents encouraged, published and saved her work, Elizabeth Barrett has one of the largest collections of juvenilia of any English-speaking writer.

A young illness affecting her spine and movement led to Elizabeth being given (and then continuously taking) laudanum, morphine and opium as a child for pain. Being addicted to these somewhat serious drugs and taking them throughout her lifetime is generally acknowledged to both have helped and hindered her in life. Her constant frail health was negatively affected by these chemicals, but they also may have contributed to her originality and imagination when writing her poetry.

A young illness affecting her spine and movement led to Elizabeth being given (and then continuously taking) laudanum, morphine and opium as a child for pain. Being addicted to these somewhat serious drugs and taking them throughout her lifetime is generally acknowledged to both have helped and hindered her in life. Her constant frail health was negatively affected by these chemicals, but they also may have contributed to her originality and imagination when writing her poetry.

Barretts late teens and twenties were fraught with trauma and tragedy. Her mother passed away in 1828, and her grandmother just a few years later. After moving to the Devonshire coast to aid her frail health (by this time she had possibly contracted tuberculosis), Elizabeth endured the loss of two of her brothers. One caught a sickness visiting the family plantations in Jamaica, and the other, her favorite brother, sadly drowned in a sailing accident while visiting her in Torquay. The guilt of this tragedy stayed with Elizabeth for the rest of her life.

In 1841 Elizabeth’s life seemed to begin to turn itself around. She was struck with a few years of intense creativity, which led to the publication of several of her greatest works. Her 1842 poem “The Cry of the Children” published in a Blackwoods magazine helped bring about child labor law reform. In 1844 she published not one but two volumes of poetry, which were immediate successes. She was suddenly a household name. It was her poetry that inspired one Robert Browning to write to her and tell her of his love for her writing. They met and instantly became ardent devotees of the other. Both Browning and Barrett’s works improved (despite their work already being popular with the public). After meeting Browning, Barrett published her most famous works Aurora Leigh and Sonnets from the Portuguese. The marriage between Browning and Barrett was carried out in secrecy, and once found out Barretts father disinherited her (as he funnily enough did to all his children who married). They made their permanent residence in Italy, where they raised their son, Pen, and befriended many influential writers and artists of the day.

In 1841 Elizabeth’s life seemed to begin to turn itself around. She was struck with a few years of intense creativity, which led to the publication of several of her greatest works. Her 1842 poem “The Cry of the Children” published in a Blackwoods magazine helped bring about child labor law reform. In 1844 she published not one but two volumes of poetry, which were immediate successes. She was suddenly a household name. It was her poetry that inspired one Robert Browning to write to her and tell her of his love for her writing. They met and instantly became ardent devotees of the other. Both Browning and Barrett’s works improved (despite their work already being popular with the public). After meeting Browning, Barrett published her most famous works Aurora Leigh and Sonnets from the Portuguese. The marriage between Browning and Barrett was carried out in secrecy, and once found out Barretts father disinherited her (as he funnily enough did to all his children who married). They made their permanent residence in Italy, where they raised their son, Pen, and befriended many influential writers and artists of the day.

On this what would be her 214th birthday, we honor this timeless writer – one who inspired Edgar Allen Poe and Virginia Woolf alike. And we give you a parting few lines…

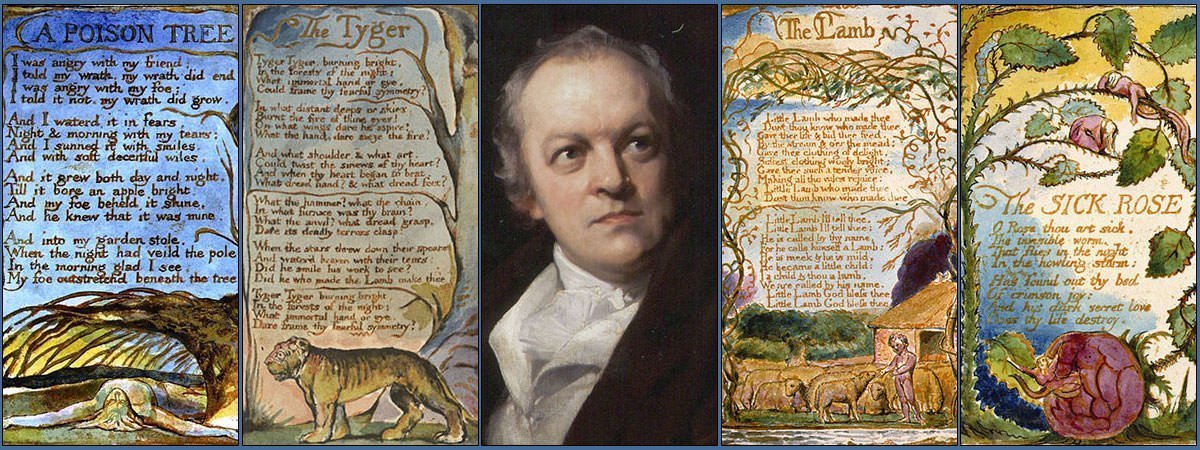

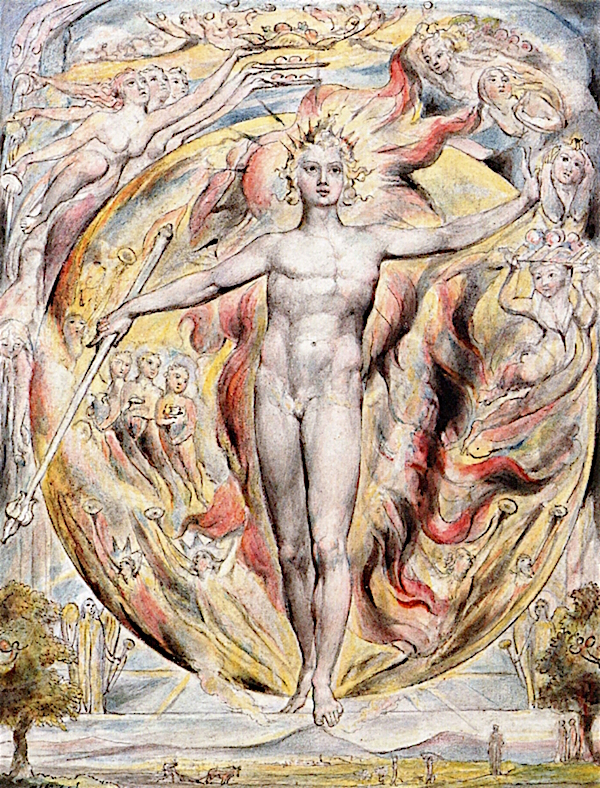

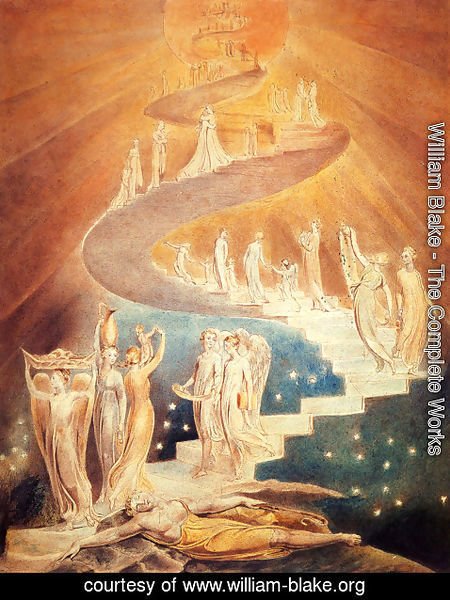

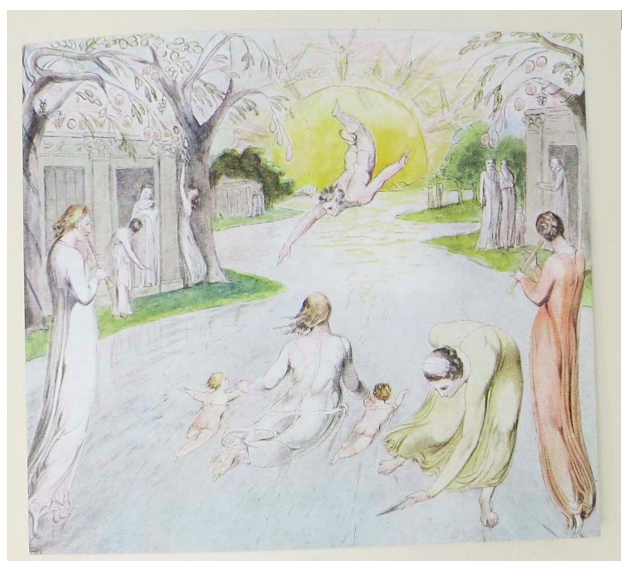

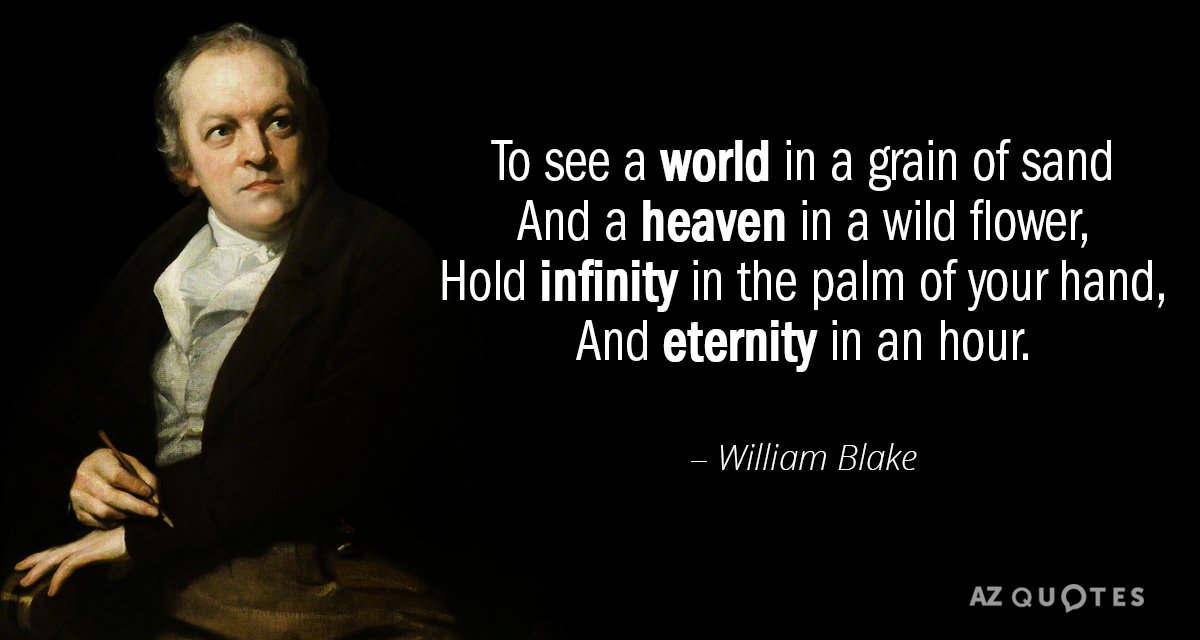

William Blake was born on November 28th, 1757 in Soho, London. He was the third of seven children (though two of his siblings died in infancy). Though his family were English dissenters, it did not stop Blake from being baptized and having a thorough biblical education – knowledge which would prove to be quite inspirational in his work later in life. Blake’s artistic side surfaced when he began copying drawings of Greek antiquities given to him by his father. It was through these copies that Blake was first introduced to works by Michelangelo, Durer and Raphael. By the time Blake was ten he had completed his formal education and was able to be sent to a drawing school in The Strand – where he not only read and avidly studied the arts but also made his first foray into poetry.

William Blake was born on November 28th, 1757 in Soho, London. He was the third of seven children (though two of his siblings died in infancy). Though his family were English dissenters, it did not stop Blake from being baptized and having a thorough biblical education – knowledge which would prove to be quite inspirational in his work later in life. Blake’s artistic side surfaced when he began copying drawings of Greek antiquities given to him by his father. It was through these copies that Blake was first introduced to works by Michelangelo, Durer and Raphael. By the time Blake was ten he had completed his formal education and was able to be sent to a drawing school in The Strand – where he not only read and avidly studied the arts but also made his first foray into poetry. At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver in London and upon his completion of his apprenticeship became a professional engraver at twenty-one. The following year, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy where he studied over the years and submitted works for exhibition. Though he disagreed with the views held by the headmaster of the time and favored more classical art rather than the popular oil paintings of the age, Blake used the years to make friends in the art world and perfect his own skills. He printed and published his first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, around 1783, and opened up his print shop with fellow apprentice James Parker in 1784. Blake began to associate with radical thinkers of the time – scientists, philosophers and early feminist icons like Joseph Priestly and Mary Wollstonecraft. Blake spent the 80s experimenting with different kinds of printing, finally moving onto relief etching in 1788. Relief etching (also called illuminated printing) would be a medium Blake would continue to use in printing his works throughout his life. In this medium, color illustrations were able to be printed alongside text. Blake has become well-known for his illuminated printing, but throughout his life he was also known for his intaglio engraving – a more standard process of engraving at the time.

At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver in London and upon his completion of his apprenticeship became a professional engraver at twenty-one. The following year, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy where he studied over the years and submitted works for exhibition. Though he disagreed with the views held by the headmaster of the time and favored more classical art rather than the popular oil paintings of the age, Blake used the years to make friends in the art world and perfect his own skills. He printed and published his first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, around 1783, and opened up his print shop with fellow apprentice James Parker in 1784. Blake began to associate with radical thinkers of the time – scientists, philosophers and early feminist icons like Joseph Priestly and Mary Wollstonecraft. Blake spent the 80s experimenting with different kinds of printing, finally moving onto relief etching in 1788. Relief etching (also called illuminated printing) would be a medium Blake would continue to use in printing his works throughout his life. In this medium, color illustrations were able to be printed alongside text. Blake has become well-known for his illuminated printing, but throughout his life he was also known for his intaglio engraving – a more standard process of engraving at the time.

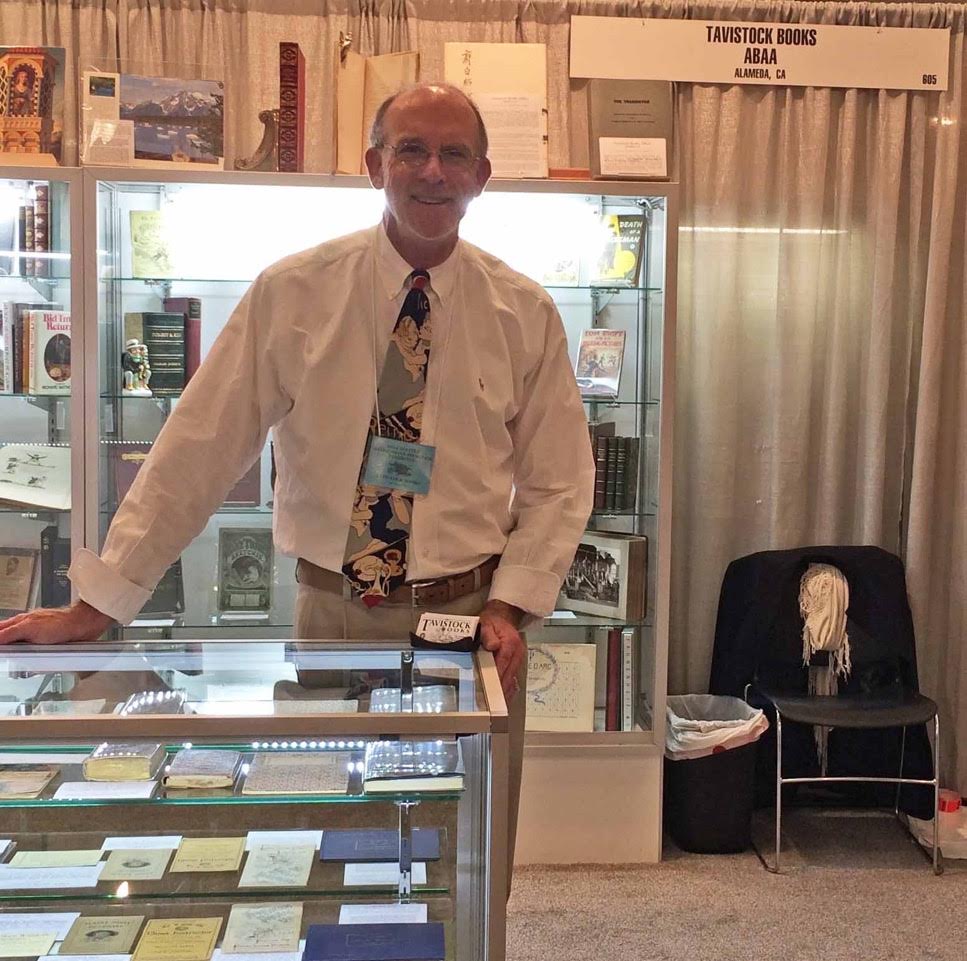

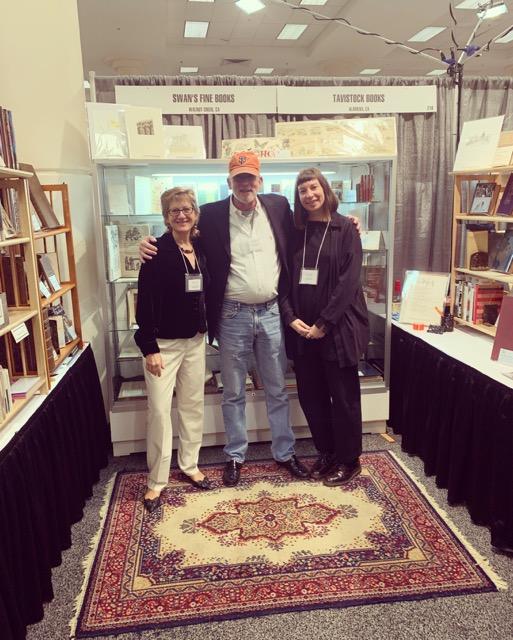

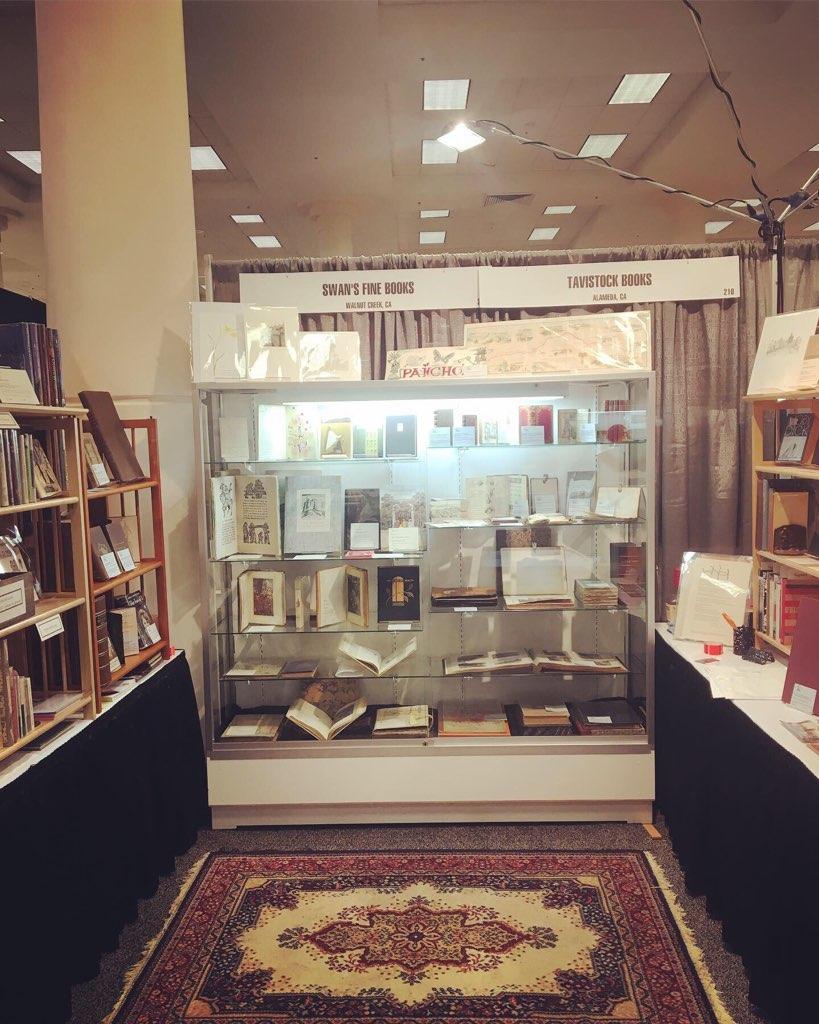

When I started doing fairs back in the early 90s, book fairs were an opportunity for collectors to see a bunch of material they may not otherwise have access to.

When I started doing fairs back in the early 90s, book fairs were an opportunity for collectors to see a bunch of material they may not otherwise have access to.

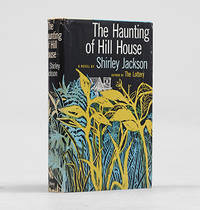

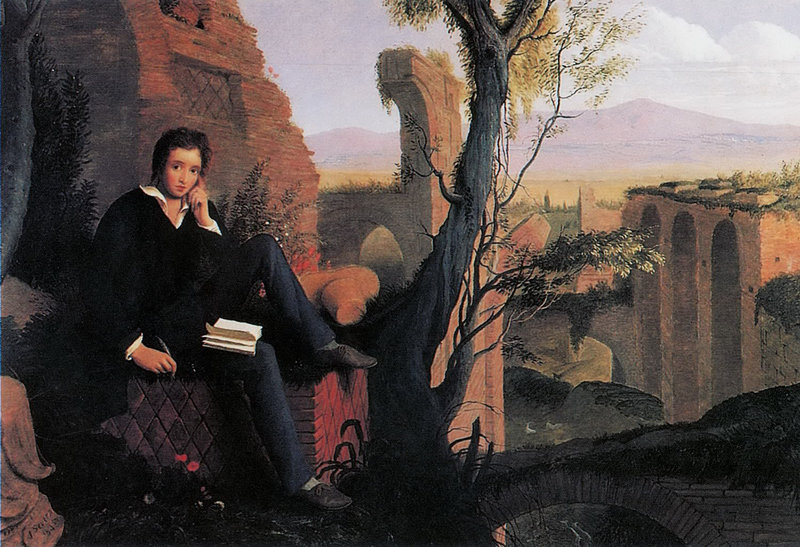

In the summer of 1816, Shelley befriended one of his first powerful and influential authors – Lord Byron. Percy and Mary spent a season with Byron in Switzerland – the summer ended up being one of the most important of Shelley’s life. Byron helped inspire the young radical, and Shelley wrote his romantic poem Hymn to Intellectual Beauty after an afternoon with Byron. It was during this summer, funnily enough, that Byron’s guests and friends were inspired to have a horror write-off. This writing competition of sorts was the inspiration behind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Upon their return to England at the end of the year, it was discovered that Shelley’s wife, Harriet, had committed suicide. As unfortunate as the event was, it incited Shelley and Mary to finally marry. The two settled in a small hamlet in Buckinghamshire, where they befriended poets John Keats and Leigh Hunt – both of which would prove to be invaluable friends to Shelley in his last years. It was in these years that Shelley wrote and published a bulk of his most well-known works, including The Revolt of Islam and Prometheus Unbound, the latter of which is widely considered to be his most beloved epic work.

In the summer of 1816, Shelley befriended one of his first powerful and influential authors – Lord Byron. Percy and Mary spent a season with Byron in Switzerland – the summer ended up being one of the most important of Shelley’s life. Byron helped inspire the young radical, and Shelley wrote his romantic poem Hymn to Intellectual Beauty after an afternoon with Byron. It was during this summer, funnily enough, that Byron’s guests and friends were inspired to have a horror write-off. This writing competition of sorts was the inspiration behind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Upon their return to England at the end of the year, it was discovered that Shelley’s wife, Harriet, had committed suicide. As unfortunate as the event was, it incited Shelley and Mary to finally marry. The two settled in a small hamlet in Buckinghamshire, where they befriended poets John Keats and Leigh Hunt – both of which would prove to be invaluable friends to Shelley in his last years. It was in these years that Shelley wrote and published a bulk of his most well-known works, including The Revolt of Islam and Prometheus Unbound, the latter of which is widely considered to be his most beloved epic work.

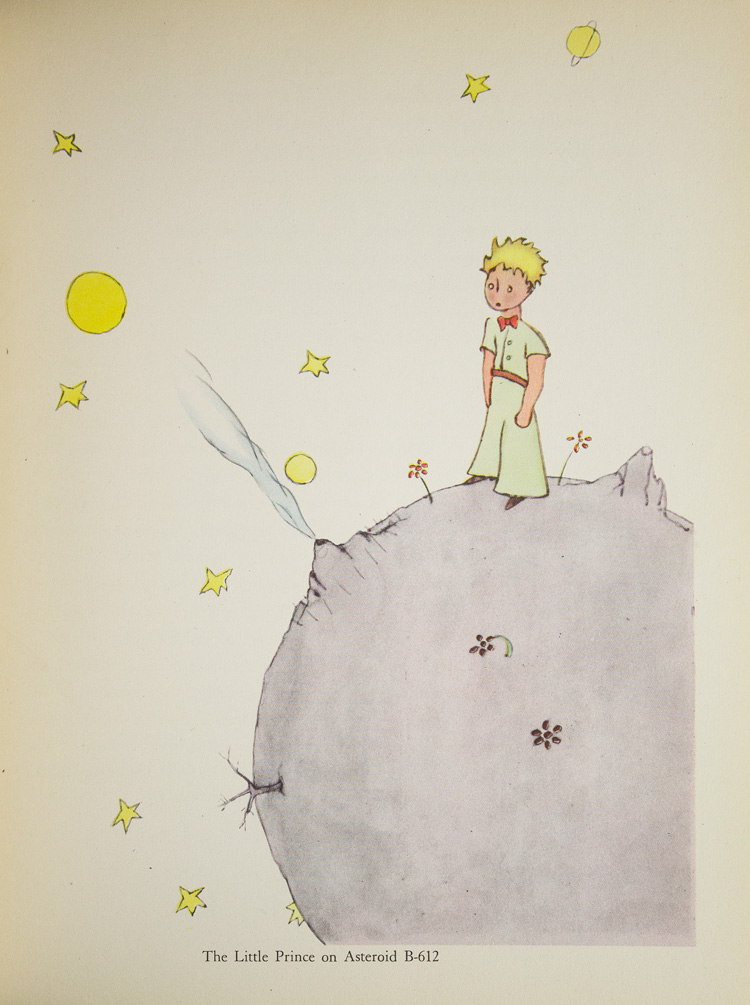

So said the Little Prince – an absolutely beloved character in the canon of Western Literature. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote this story, a children’s story on the outside and a very adult study of human nature and morality on the inside. Saint-Exupéry, a French national, had fled Europe at the onset of World War II and wrote much of his tale during his 27 week stay in North America and Canada. Now normally we would do a blog on Saint-Exupéry’s life story and how he came to write such a popular and precious children’s tale, but today we are speaking of a specific day in this author’s life… the day he disappeared from the skies.

So said the Little Prince – an absolutely beloved character in the canon of Western Literature. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote this story, a children’s story on the outside and a very adult study of human nature and morality on the inside. Saint-Exupéry, a French national, had fled Europe at the onset of World War II and wrote much of his tale during his 27 week stay in North America and Canada. Now normally we would do a blog on Saint-Exupéry’s life story and how he came to write such a popular and precious children’s tale, but today we are speaking of a specific day in this author’s life… the day he disappeared from the skies.

Unfortunately,

Unfortunately,

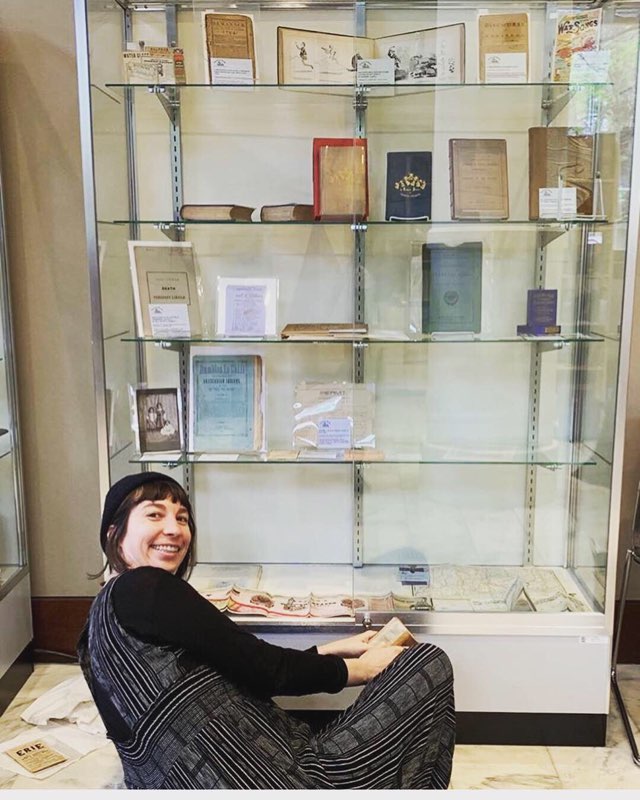

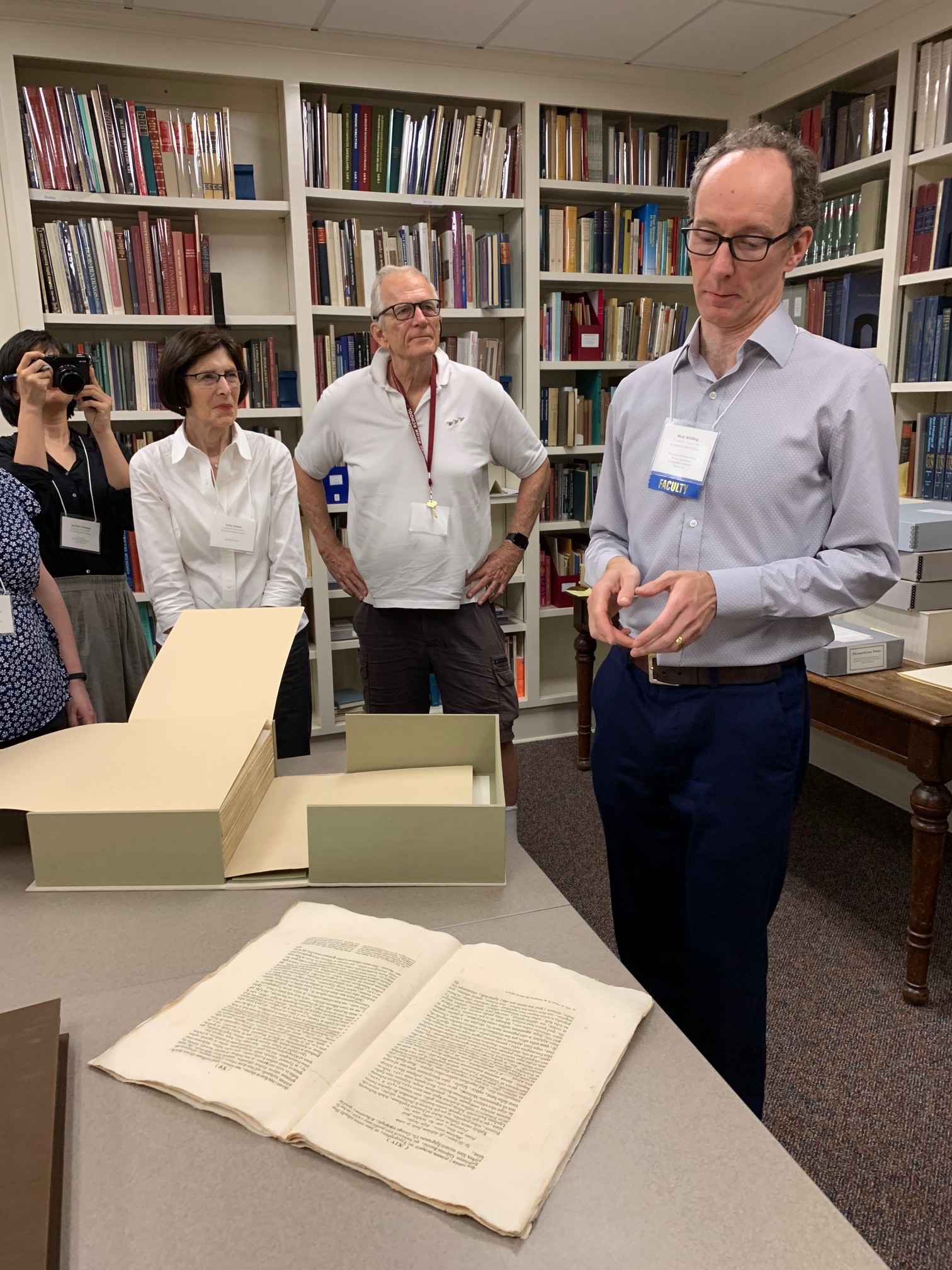

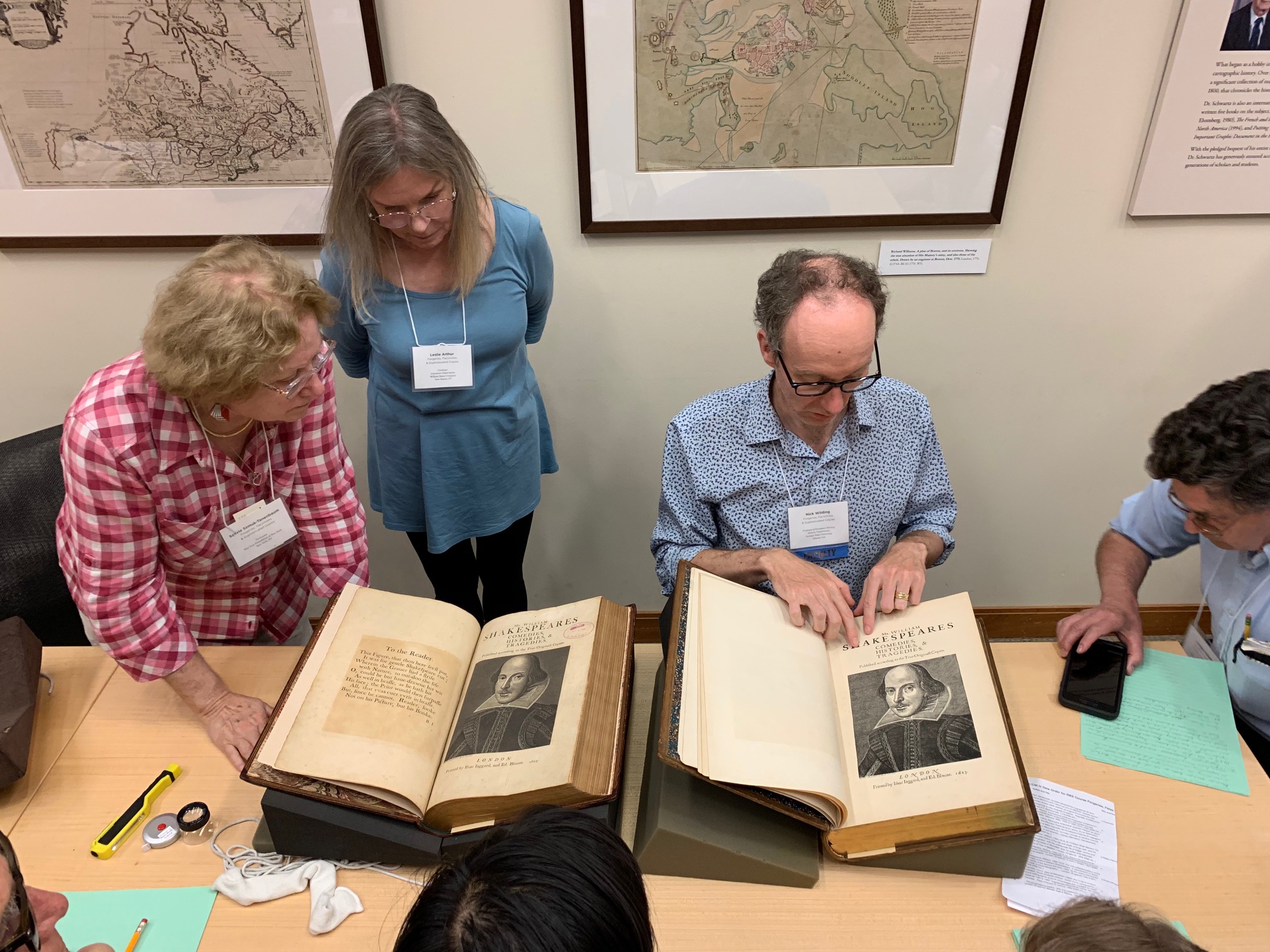

For those new to RBS, things kick off Sunday afternoon, 5ish. There’s a reception, a Michael Suarez welcome speech & restaurant night. The latter an opportunity for ~ 10 students to share a meal at one of the local ‘Corner’ restaurants, in my case, Lemongrass Thai. Wonderful food, wonderful company!

For those new to RBS, things kick off Sunday afternoon, 5ish. There’s a reception, a Michael Suarez welcome speech & restaurant night. The latter an opportunity for ~ 10 students to share a meal at one of the local ‘Corner’ restaurants, in my case, Lemongrass Thai. Wonderful food, wonderful company!