By Kate Mitas

Getting to Know Your Archive

Now that you know your archive is about, say, Alaskan beauty pageant contestants or Italian motor scooters (to use two of Lorne Bair’s examples from the last blog in this series), it’s time to write up a snazzy description and send the archive out into the world, right?

Well, no.

As with anything else, first impressions can carry a lot of weight, but they exist to be refined, deepened, and, in some cases, overturned completely by later information. This is especially important to keep in mind when you’re dealing with archives: unlike books, whose (expected) contents are often already known by your customer and documented in bibliographical references, archives, in a sense, don’t really exist until they’re catalogued. Cataloguing an archive defines, as well as describes, its contents for a potential customer. That’s part of what makes archives so exciting to work with, but it also increases the risk of misleading your client (and/or yourself) by imposing a narrative, rather than letting the narrative be dictated by the material.

Physical Content

First things first, to borrow from Brian Cassidy’s oft-repeated maxim at CABS: Look. At. The. Archive.

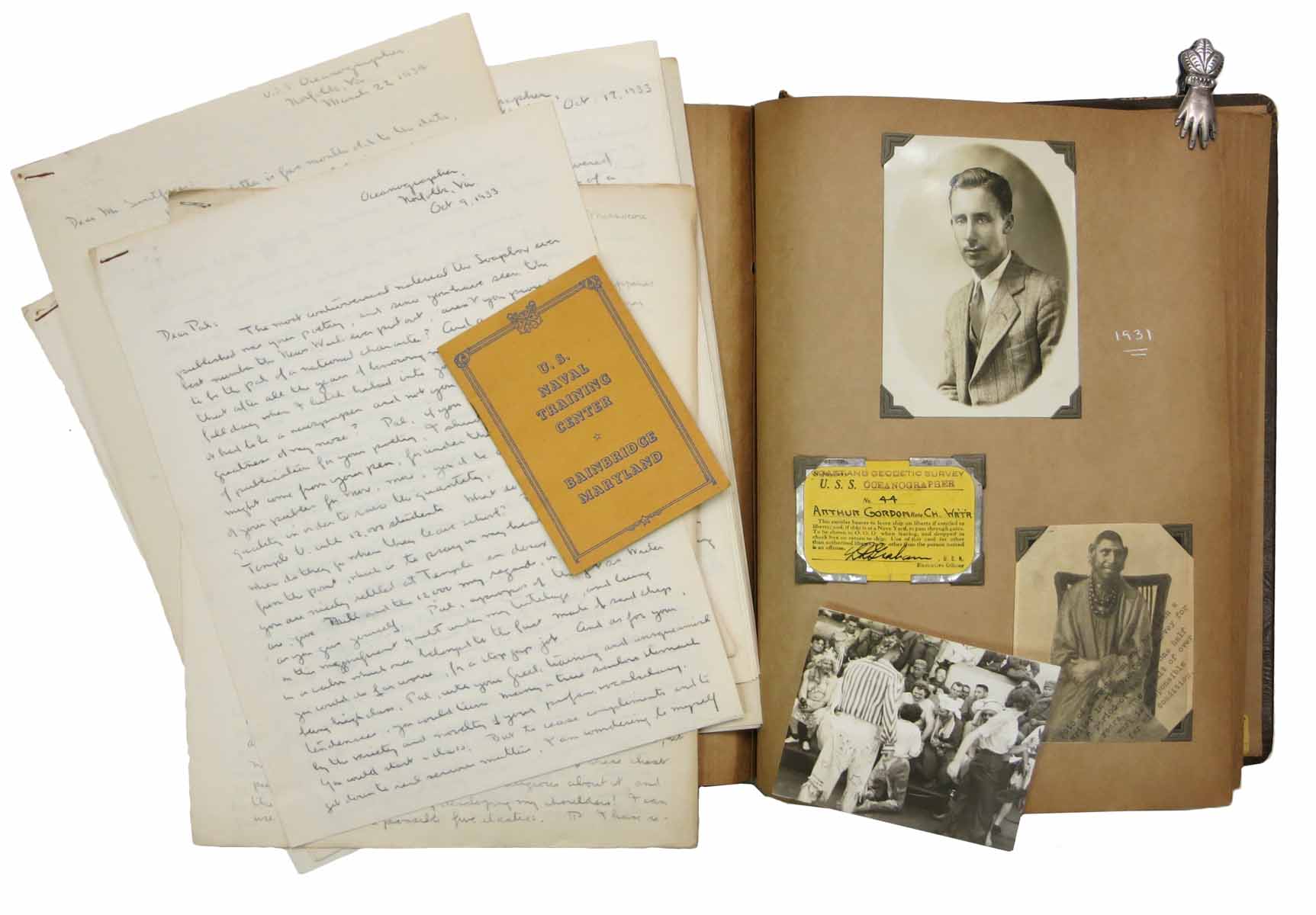

An archive in progress — stay tuned!

It can be easy to skip over an archive’s physical content and dive right into those letters, or diaries, or photographs — after all, that’s the fun part, when you get to read on the job(!), hunt for clues, do research, and, in general, be utterly and exquisitely nerdy. In contrast, cataloguing the physical content of an archive is tedious, sometimes mind-numbingly so: you count the different things in the archive, and you figure out what they’re made of and how big they are, and, if you’re like me, you also probably recount something at least once, because the phone rang in the middle and you want to make absolutely sure you’ve gotten it right. So what’s the big deal about physical content?

Put simply: everything in an archive is a function of its physical content. It’s impossible to draw accurate conclusions about an archive’s intellectual content without knowing its actual composition, and, consequently, to determine a commercial value based on those factors. (Note the qualifiers, here. Sometimes it’s far more practical to slap a price on a minimally-catalogued archive and send it on to another bookseller who knows more about the subject. More on this later.)

Take those photographs of Alaskan beauty pageant contestants, for example. They might be the most interesting subsection of Alaskan life you’ve ever seen, but what if they’re real photo postcards instead of photographs, issued as souvenirs at an annual fair in downtown Anchorage? Or worse, half-tone reproductions? Conversely, what if your Alaskan pageant contestants are only in ten photographs in an album of 300, all featuring contestants at beauty pageants held around the country during a 20 year period (which would be a pretty kick-ass archive, by the way)? And what if those ten Alaskans are scattered throughout the album, rather than grouped together?

You get my point: establishing an archive’s physical content is a way of applying quantifiers to aspects of valuation like rarity and significance, as well as forcing you to reconcile the parts of an archive you found interesting (Alaskan beauty pageant contestants) with the likely intent of the person who formed the archive (beauty pageant contestants). It’s a way of grounding your enthusiasm and, ultimately, making you focus on what an archive actually is, rather than what you might want it to be.

Not everyone includes the same amount and kinds of information when describing an archive’s physical contents. Nevertheless, here is a list of general factors that we include at Tavistock, and which I’ve found to be helpful:

For textual material:

- number of pages and size of leaves

- if unique, whether the material is manuscript and/or typescript

- if manuscript, overall legibility

- if printed, whether professionally or not

- estimated word count (of manuscript/typescript material)

For photographic/visual material:

- number and type of photographs/images, with a breakdown by category

- photographic process*

- color, black and white, etc.?

- professional vs amateur

This list is far from complete, of course — you’ll note there’s nothing here about film, for example, since we almost never handle it — but these attributes are a good place to start when determining the physical content of most textual and photographic archives from the mid-20th century and earlier.

* For a good reference on how to distinguish the type of photographic process used, with a handy fold-out chart for identification, we recommend James Reilly’s Care and Identification of 19th Century Photographic Prints.

Next up in the series: Intellectual Content and Research Methods