In honor of Spooktober (a spooky October, of course), today our blog calls on our love of the movie Hocus Pocus, as we focus on a magical text, a witches handbook – called Grimoires.

By definition, a grimoire is a “a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and how to summon or invoke supernatural entities such as angels, spirits, deities, and demons” (Davies). I first came across the idea of antiquarian grimoires via, you’ll be surprised to learn…. Tiktok. The latest and “greatest” of social media platforms is full of information. Some interesting, some shocking, and some downright useless, true. But suddenly on my “for your page” there appeared an antiquarian bookseller (Reid Moon, Moons Rare Books) discussing an early grimoire in his inventory, and I was hooked.

It is not unusual to find witchy empty journals for a witches Book of Shadows’ at Barnes and Noble these days, which differs from Grimoires in the fact that grimoires (a French word derived from the French term for “grammar”) quite literally translate to the grammar of magic. Bookseller William Kiesel explained that “Typically, grimoires are often manuals of practice that give recipes, operations, rituals and perhaps even spells.” Grimoires are then… manuals, where practitioners of alternative methods of healing, spirituality, medicine and more would put their practices within for easy reference later on (literally “grimoires” throughout history run the gamut – from ancient Egyptian magical inscriptions on cuneiform tablets and amulets to the medieval period texts by Popes and doctors, even, to modern day). These days, antiquarian grimoires hold a special sort of fascination in the book collecting community, as they allow for a more individualized look at spirituality, unlike and sometimes even opposing conventional, organized religion.

One of the pentacles found in the Key of Solomon.

While grimoires were mainly popular between the 1500s and 1900s, there is evidence of their existence (as a physical copy of a written text) as far back as one of the most famous of all grimoires, the Key of Solomon (or Testament of Solomon, two separate works but sometimes confused with each other) written in Greek in the 1st millennium CE. When rumors of its existence first began to circulate, it was claimed that this text included incantations for summoning demons and described them being used to cure cases of possession. The actual Testament of Solomon, while not written by Solomon himself (this can get confusing in the realm of grimoires), is one of the oldest surviving magical texts, dating back to one of the first five centuries A.D. It carries descriptions of a ring that could bind demons from doing harm, and was written as a source of information and warning to its readers.

As Christianity gained favor throughout the world, many magical texts or books centered on demonology and other potentially pagan beliefs were banned, burned and their authors silenced. A few of the more notable works that remain are often ones dealing in “natural magic” rather than “demonic magic”, as during the medieval period the former was allowed – it could be construed as a way to praise and celebrate all that God placed upon the earth for others to enjoy. Demonic texts, on the other hand, were wildly unacceptable. Another Key of Solomon appeared around this time (Solomon a popular figure for authoring these texts, evidently), and then a German abbot and occultist (I know, the irony) named Trithemius supposedly had a book of magic based on the New Testament character Simon Magus – a contemporary of Jesus Christ who was vilified and demonized by the church as a devil worshipper, despite performing similar “miracles” that were attributed to the former.

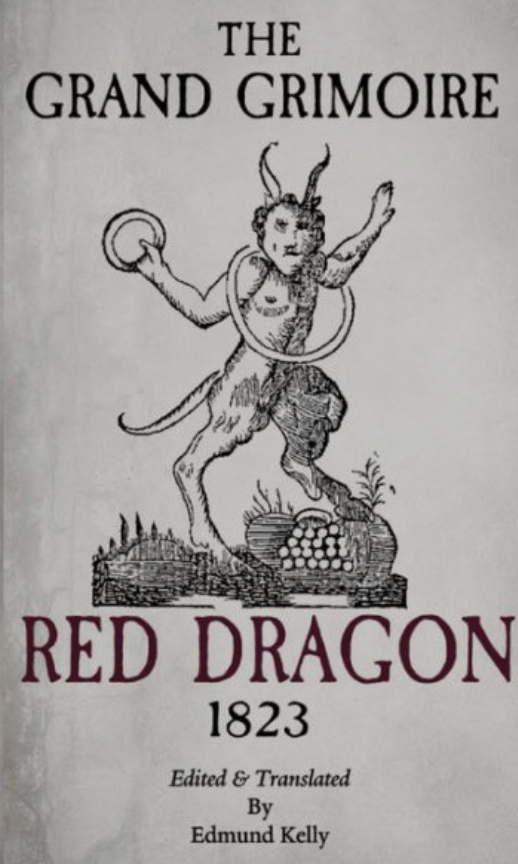

Several grimoires make their way onto the scene in the 1500s, with a steady stream of them from thereon after. Some of these include Les Secrets merveilleux de la magic naturelle du petit Albert (1272), the Grand Grimoire (1521), Le Dragon Rouge (published in 1822 but supposedly dating back to 1522), and the Grimoire of Armadel (written in the 1600s, not published until 1980). As time passes and the ability to write becomes more commonplace, availability of paper and writing utensils increase, more and more grimoires emerge. Notable antiquarian collections of grimoires can be found at the Cornell University Library, the Ritman Library in the Netherlands, and the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in the UK.

Several grimoires make their way onto the scene in the 1500s, with a steady stream of them from thereon after. Some of these include Les Secrets merveilleux de la magic naturelle du petit Albert (1272), the Grand Grimoire (1521), Le Dragon Rouge (published in 1822 but supposedly dating back to 1522), and the Grimoire of Armadel (written in the 1600s, not published until 1980). As time passes and the ability to write becomes more commonplace, availability of paper and writing utensils increase, more and more grimoires emerge. Notable antiquarian collections of grimoires can be found at the Cornell University Library, the Ritman Library in the Netherlands, and the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in the UK.

The extensive history of the grimoire and like texts prove that one thing is for sure and certain – magic, and the human interest in magic/the ability to witness things not easily attributed to science have inspired us for thousands of years. And here in witch-season we don’t expect it to let up any time soon! Happy Spooktober!