Born on London’s Fleet Street on October 24, 1794, Richard Bentley came into the publishing world thanks to his family. When Bentley started a firm with his brother in 1819, he was the third generation to enter the profession. Bentley would go on to pursue a number of partnerships and weather the volatile economic climate of Victorian England to become, according to the DNB, “arguably one of the finest printers in London.”

In 1829, Bentley undertook a partnership with Henry Colburn, who had encountered financial difficulty and owed Bentley money. Rather than watch Colburn default, Bentley entered a rather lopsided agreement. They merged their firms. For a period of three years, Bentley would act as bookkeeper and procure new manuscripts for publication. He would also invest £2,500 over that time period and receive 40% of the firm’s profits. Colburn, meanwhile, would provide 60% of the capital and receive 60% of the profits. If the partnership failed in less than three years, Bentley would buy out Colburn for £10,000. Colburn would then publish only what he’d published before the partnership.

From the start, however, the partnership was quite profitable, largely because they chose to cater to public taste. They took advantage of the interest in “silver fork novels,” that is, fashionable novels about the lives of aristocrats and other high-society members. For instance, Colburn and Bentley published works by Catherine Gore and Benjamin Disraeli. They also published a fair number of novels in the triple-decker format, because this was the format preferred by circulating libraries, and they advertised heavily (indeed, in three years, the firm spent over £27,000 on advertising).

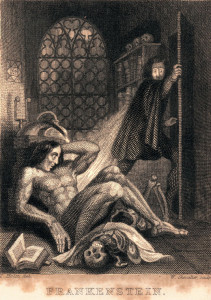

Perhaps their greatest triumph was the Standard Novels series. They focused on popular titles that were previously available only in the expensive triple-decker set, publishing them for the first time in inexpensive single volumes. Colburn and Bentley came up with an ingenious approach to publishing popular works of the era; they solicited the authors to revise their novels enough that the works would be eligible for a new copyright–and short enough to publish in a single volume. One such author was Mary Shelley, who was more than happy to get a new audience for Frankenstein. (There was one caveat, however: when Shelley assigned copyright to the Standard Novels series, she precluded the novel’s publication elsewhere, and it wasn’t published in England again until the 1860’s.)

The first Standard Novels book was The Pilot by James Fenimore Cooper. From there, the series went on to include the first inexpensive reprints of Jane Austen’s novels and a number of American titles. Colburn and Bentley published the first nineteen titles together, but after the partnership fell apart Bentley continued the series on his own. It was incredibly successful, making the firm £1,160 in the first year. And over the course of 124 years, the series came to include 126 titles.

Not all of Colburn and Bentley’s endeavors proved equally profitable. They ended up selling over half the 550,000 books in the National Library of General Knowledge series as remainders. And the Juvenile Library lost the firm £900. The Library of Modern Travels and Discoveries never even made it to the printing press, and the firm passed up Sartor Resartus by the then-unknown Thomas Carlyle. Meanwhile the cost of copyrights continued to rise. By 1832, Colburn and Bentley had stopped speaking, relying on lawyers and clerks to manage their affairs.

On September 1, 1832, Colburn and Bentley’s partnership was officially dissolved. Bentley bought out Colburn for £1,500. He got to keep the office and drop “Henry Colburn” from the firm’s name. He also paid Colburn £5,580 for copyrights and other materials. For his part, Colburn agreed to limit his publication activities…but violated this part of the agreement almost immediately. Thus Colburn and Bentley went from business partners to bitter rivals. Bentley received a boost in reputation when he was named Publisher in Ordinary to the king in 1833, but that appointment brought him no additional business of any significance.

Nevertheless, Bentley enjoyed early success on his own. He published Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), which sold well for years on end. Bentley also published William Harrison Ainsworth’s Rookwood the same year. The novel was a bestseller and required two more editions. Bentley soon gained a reputation for publishing excellent literature, and he named such respected writers as Frances Trollope, William Hazlitt, and Maria Edgeworth among his authors. Bentley expanded his audience by publishing works in multiple formats, serializing them in Bentley’s Miscellany in addition to publishing them in single-volume or triple-decker editions.

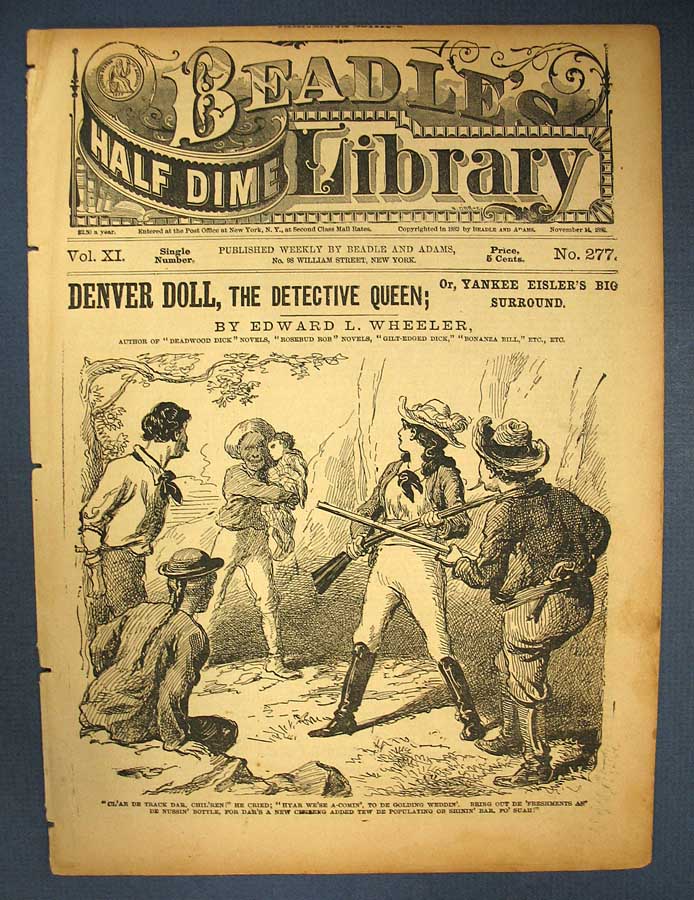

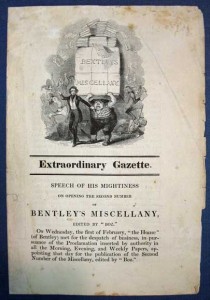

Here Dickens “paraphrased the average Royal speech, and by the use of bombastic and ponderous expressions announced the coming of ‘Oliver Twist'” (Eckel).

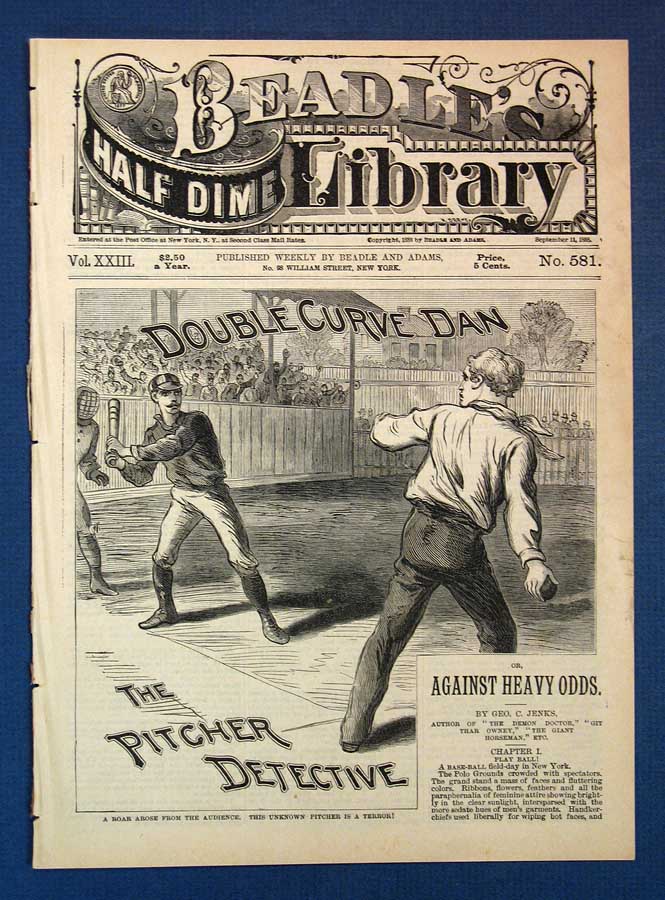

Bentley launched Bentley’s Miscellany in January 1836. He invited Charles Dickens, then known for Pickwick Papers, to act as editor. Dickens took the job, which came with a salary of £40 a month. He also agreed to provide novels for serialization in the periodical. But Dickens soon enjoyed celebrity status and believed he deserved higher pay. Dickens and Bentley would negotiate Dickens’ contract a total of nine times. In their final agreement, Dickens was to receive £1,000 per year, plus additional payment for his novels. Yet the two had other differences that proved insurmountable, and in the end Dickens bought out his contract for £2,250 and purchased the copyright to Oliver Twist, serialized in 1837 and largely responsible for the periodical’s success.

When Dickens stepped down in February 1839, William Harrison Ainsworth took the editorial helm. Almost immediately, circulation dropped and costs shot up. Ainsworth lacked Dickens’ following–and his eye for engaging content. The quality of Bentley’s Miscellany decreased considerably. Through the 1840’s and 1850’s, Bentley used Miscellany to promote his own publications, which did include the occasional literary masterpiece like Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Then in 1843, the Crimean War broke out. England’s economy took a nosedive, and the book trade suffered considerably. Bentley would struggle for the next two decades. He started a sixpenny newspaper, Young England, which lasted only fourteen issues. In 1849, the House of Lords ruled that copyrights on foreign works were no longer valid, so other firms began publishing cheap versions of works that Bentley had paid for the rights to publish. Though this decision was overturned in 1851, it still did damage not only to Bentley, but to the publishing industry at large. By 1853, Bentley had reduced the price of his books in an attempt to increase sales volume. The tactic didn’t work. In 1857 Bentley sold off copyrights, plates, steel etchings, and other materials to stave off bankruptcy.

Then in 1859, Bentley made a risky move. He decided to compete with the Edinburgh Review and the Quarterly Review with his own Bentley’s Quarterly. Robert Cecil, John Douglas Cook, and William Scott were named editors. Though critics praised the periodical, the public expressed little interest and only four issues were published. In June of the same year, Bentley tried again with Tales from Bentley, where he reprinted stories that had already appeared in Bentley’s Miscellany. This was a more successful venture.

Bentley purchased Temple Bar Magazine in January 1866, naming his son George the editor. Two years later, Ainsworth ran into financial difficulties and sold back Bentley’s Miscellany to Bentley for a mere £250. Bentley merged the two publications and built himself an excellent roster of authors: Anthony Trollope, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and Wilkie Collins all appeared. But then tragedy struck. Bentley fell from the railway platform at Chepstow station and broke his leg. His son George immediately took over daily operations at the firm. Bentley would never recover from the injury, and he passed away four years later in September 1871.

Today Bentley perhaps best remembered, as related above, as the man who first brought to the public, in his Miscellany, Dickens’ classic novel, Oliver Twist. For that one publication, we are eternally grateful.