When Clement Clarke Moore published “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” anonymously on December 23, 1823 in the Troy Sentinel, he couldn’t have known that it would become an international phenomenon. But the poem not only gave names to Santa’s eight reindeer. The illustrations of the poem’s reprints significantly impacted our perception of Santa Claus. Caricaturist Thomas Nast would later illustrate jolly old Saint Nick, cementing our concept of him as a jolly. bearded man. And Coca-Cola would eventually be the first to bring us Santa in a red coat. We can thank Washington Irving and Charles Dickens, however, for resurrecting Christmas as a holiday for joyful family celebration.

A Brief History of Christmas

Before Christianity took hold, pagan rituals were routinely honored on the winter solstice. On this day, people would celebrate the triumph of light over darkness. Early church officials, eager to supplant these rites with their own, wisely chose to make Christmas celebrations correspond to these pagan rituals. The strategy had one caveat: the Church couldn’t dictate how people would celebrate Christmas. Thus, Christmas had mostly replaced pagan holidays by the Middle Ages, but holiday observances were usually far from pious. Believers might go to church, but afterward citizens would gather for rowdy festivals similar to Mardi Gras. Each year a student or beggar would be named “Lord of Misrule,” and festival attendants would play the role of his subjects. Meanwhile the poor would go to the homes of the rich to demand food and drink. Non-compliant homeowners risked mischief.

But Oliver Cromwell proved to be the original Grinch. A staunch Puritan, Cromwell believed that Christmas was a decadent and unchristian holiday. When he took over in 1645, he vowed to rid England of such indulgences and cancelled Christmas. In 1660 Charles II was restored to the throne by popular demand and reinstated the holiday. But the holiday wouldn’t immediately take hold. By Dickens’ time, the Industrial Revolution had all but destroyed the holiday in Great Britain–for most people, Christmas was still a work day.

Meanwhile the Puritans had left England to settle in the New World. For the most part, Christmas went uncelebrated in the colonies. In Boston the observation of Christmas even bore a five-shilling fine from 1659 to 1681. (Jamestown was a notable exception: Captain John Smith–the first person ever to consume eggnog–reported in 1607 that the settlement happily enjoyed the holiday.) The American Revolution proved a death knell for traditions of British origin, so Christmas again fell out of favor. It would not be declared a national holiday in the United States until June 26, 1870.

Washington Irving, the Real Father Christmas?

When Washington Irving published Knickerbocker’s History of New York (1809) under the pseudonym Dietrich Knickerbocker, New Year’s Eve was New York’s only real winter holiday. The book parodied American life, and Irving satirized the traditions of New York’s Dutch settlers. He poked fun at their patron saint, Nicholas, whom they called “Sanct Claus.” In Irving’s account of Oloffe the dreamer, Oloffe, a prophet and land speculator, dreams of a night where “the good Saint Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents for children.” Irving’s St. Nicholas not only delivers presents to children in a sleigh; he also smokes a pipe and places the presents in stockings hung by the chimney.

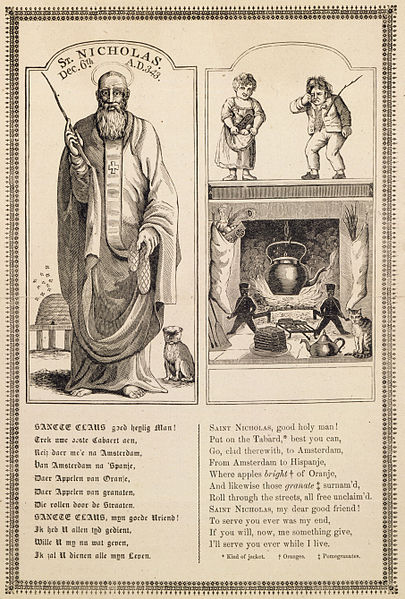

John Pintard’s St. Nicholas isn’t quite the jolly figure we imagine today!

Irving had some unsolicited assistance in St. Nick’s makeover. New York Historical Society founder John Pintard publicized an engraved picture of St. Nicholas–admittedly looking less than merry–as a symbol of New York City. But Americans remained ambivalent about the holiday. Members of different religious denominations had different concepts of what the holiday should be; some saw Christmas as sacred, while others still believed it blasphemous. Observation was spotty at best, though enterprising Boston merchants advertised ritual Christmas gift exchange as early as 1808.

Irving moved abroad in 1815, and it was not until several years later that he would write another bestseller. The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon was published in several installments from 1819 to 1820. Sandwiched in between American classics like “Rip Van Winkle” (first installment) and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (sixth installment), Irving published five Christmas stories in The Sketch Book’s fifth installment on January 20, 1820. He’d spent time at Astor Hall, recently leased from Adam Bracebridge by James Watt and passed the Christmas holiday with the Watt family. Irving was charmed by their Christmas traditions, reinventing Watt as the benevolent “Squire Bracebridge” in “Bracebridge Hall.” In “Christmas,” Irving writes, “But in the depth of winter, when nature lies despoiled of every charm and wrapped in her shroud of shielded snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources.” He would later explain the tradition of hanging mistletoe to American readers with a footnote in “Christmas Eve.” Irving believed that America could use a dose of English Christmas tradition, particularly the part where the poor are welcomed into the homes of the wealthy for a meal.

Historians mostly agree that Irving idealized the English country Christmas in The Sketch Book, but the veracity of his accounts wasn’t important to Americans. They embraced Irving’s stories. Then in 1828, the New York City Council had to create its first police force in response to a Christmas riot. The upper class decided it was time to reinvent the holiday, and Irving’s accounts fit the bill. By 1835, New Yorkers had all but abandoned Christmas revelry in favor of more idyllic celebrations at home. Christmas was revived in America.

Charles Dickens Follows Irving’s Footsteps

Charles Dickens visited the United States in 1842, and Washington Irving hosted a dinner in his honor on February 1 of that year. Numerous luminaries attended, and the event made headlines. When Dickens addressed the audience and thanked his host, he admitted his own devotion to Irving: “I say, gentlemen, I do not go to bed two nights out of seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm upstairs to bed with me.” In The Pickwick Papers, Dickens evokes Irving’s Squire Bracebridge in the character of Mr. Wardle, who merrily reminds his guests that it’s customary to while away the hours of Christmas Eve with games and ghost stories. Dickens again adapts Irving’s presentation of Christmas in A Christmas Carol, placing them in Mr. Fezziwig’s hall and in the home of Scrooge’s nephew, Fred. Thus he takes Christmas out of the country manor and brings it to working class London. Dickens’ Christmas is also centered on family and children, rather than church or community, another paradigm shift that Victorians readily embraced.

Dickens brought suit against five defendants for selling a piratical edition of ‘A Christmas Carol.’ Only one fought the charges, and the account makes for interesting reading!

Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in only six weeks during the autumn of 1843. It was published on December 19, and all 6,000 copies sold out that day. Dickens had chosen to illustrate the book with colored plates, but the expense associated with that method cut into his profits. It would be the first and only book he published with such plates. The illustrations, however, helped to bring Dickens’ Christmas to life and have since inspired a number of talented illustrators–not to mention printers and book binders who have also been taken with the work. A Christmas Carol has never gone out of print, and so many editions exist that the book is the perfect subject for a single-title collection. Dickens would write other Christmas tales, but none of these would have such an influence on the way the holiday was celebrated. Dickens’ exhausting schedule of reading tours–the first of which was for A Christmas Carol– doubtless helped promulgate his vision of Christmas, as well.

Washington Irving and Charles Dickens helped to pave the way for a rich tradition of Christmas literature, ranging from community cookbooks to children’s books. But these contributions are merely one facet of the authors’ incredible legacies.

Related Posts:

Why Did Charles Dickens Write Ghost Stories for Christmas?

Charles Dickens Does Boston

Charles Dickens’ Debt to Henry Fielding

Happy Birthday, Washington Irving!