When you think of the word “Dickensian” what comes to mind? We would not be surprised if you mentioned soot-covered children working in factories, or angry adults beating each other down with vicious words and persnickety actions. Then again… what comes to mind if we say “Dickensian Christmas”? I’ll bet an entirely different view comes to mind. Perhaps you see a warm and cozy drawing room, children playing by a large fire, adults jolly and laughing over punch with a large tree in the corner and candles lit on its branches. Sound familiar? Well it isn’t an accident. There is an old story (a myth, if you will) that on the day Dickens died, as the news was ravaging through the streets of London, a small costermonger’s daughter said with dawning horror, “Mr. Dickens is dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?” Whether this story is based in reality or not, the feeling still remains… Dickens is a name commonly associated with the holidays the world over. We’d like to examine why that is and what we can learn from it this particular holiday season.

We have published several blogs before reviewing Dickens’ childhood experiences, and the traumas he endured as a youth. Being one of the unwashed and poor factory children we associate with the word “Dickensian” was what led him to spend his life working with social reform to aid the poor and undervalued members of society. How then did he become so widely associated with the holiday that a poor vegetable seller’s daughter thought his death might mean the end of Christmas forever? For Dickens, it was easy. His childhood made him never want to experience such a Christmas again. He gravitated towards positivity, light and joy – and made sure to share it with those around him. Christmas in the Dickens household (when Charles was a father himself) was legendary. He would perform magic tricks for his friends, the table would be set elaborately, his wife would make and/or supervise the making of all manner of foods, they would have a warm fire and sing/perform together… Dickens made for himself and his family the Christmas he wished for as a child.

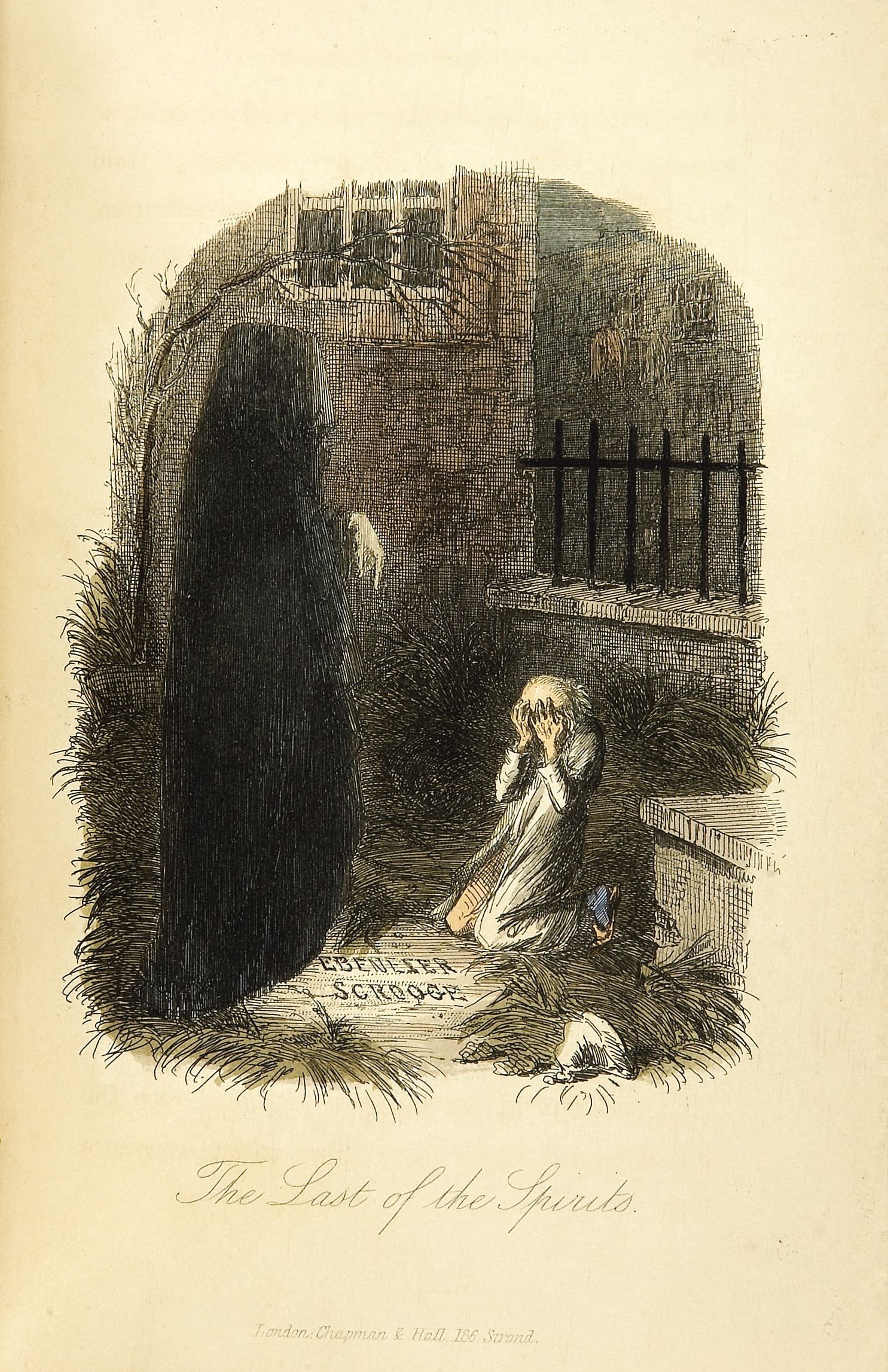

Before Dickens published A Christmas Carol (written in only a six short weeks, and published the week before Christmas at considerable expense to Mr. Dickens), he and his wife Catherine were experiencing your average hardships. They were expecting their fifth child, and supplications of money from his aging father and family, with dwindling sales from his previous works had put him into a tough financial place. In the fall of 1843, a 31-year-old Dickens was asked to deliver a speech in Manchester, supporting adult education for manufacturing workers there. His extreme interest in the subject (one that hit a bit too close to home, I believe) and his resolve to aid the lowly pushed an idea to the forefront of his mind – a speech can only do so much… to get to the crux of the matter he would need to get into the hearts, minds and homes of his readership and country. As the idea for A Christmas Carol took shape and his writings began, Dickens himself became utterly obsessed with his own story. As his friend John Forster remarked, Dickens “wept and laughed, and wept again’ and that he ‘walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed” while writing it. Dickens took the financial hit publishing it on his own, in a beautiful cloth bound book with gilt leaf edging, and colorful illustrations by John Leech.

Before Dickens published A Christmas Carol (written in only a six short weeks, and published the week before Christmas at considerable expense to Mr. Dickens), he and his wife Catherine were experiencing your average hardships. They were expecting their fifth child, and supplications of money from his aging father and family, with dwindling sales from his previous works had put him into a tough financial place. In the fall of 1843, a 31-year-old Dickens was asked to deliver a speech in Manchester, supporting adult education for manufacturing workers there. His extreme interest in the subject (one that hit a bit too close to home, I believe) and his resolve to aid the lowly pushed an idea to the forefront of his mind – a speech can only do so much… to get to the crux of the matter he would need to get into the hearts, minds and homes of his readership and country. As the idea for A Christmas Carol took shape and his writings began, Dickens himself became utterly obsessed with his own story. As his friend John Forster remarked, Dickens “wept and laughed, and wept again’ and that he ‘walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed” while writing it. Dickens took the financial hit publishing it on his own, in a beautiful cloth bound book with gilt leaf edging, and colorful illustrations by John Leech.

The book became an instant sensation, and this book – celebrating the joy, kindness and positivity possible in humans, not to mention the ability to change for the better – did even better than Dickens could have imagined. It transformed into a handbook, of sorts – how to live a successful, kind life, both in the holiday season and beyond.

So what can we here in 2020 take away from A Christmas Carol and Dickens’ obsessive love of the holiday? Well, the first thing might be to embrace the warmth of home. With all the griping about the hell that 2020 has put us through, and the harsh realities of staying home for months and months, staying away from friends, not being able to eat out or travel… perhaps one last push of 2020 can be for us all to embrace what we have right in front of us – a roof over our heads, a fire (or a heater), and good food. I realize that in past years (and in A Christmas Carol, of course) we might have not only embraced the love we could find in our own households, but invited others to experience it as well. Perhaps in 2020 the time has come to focus more of our attention on those in our immediate household. Shower them with as much love and kindness as we would use for all of those around us.

Similar to how Dickens and his family celebrated, decorate as festively and as cozily as you so choose – don’t let a lack of visitors deter you from putting together a beautiful tree, or hanging a wreath on your door. Pass the longer evenings with a great book and a hot drink, or perhaps do as Dickens did and allow your creativity to flourish. Finally take the time to write that story you’ve been meaning to, or put together a skit for your family to act out on Christmas morning. As Dickens probably did, send your letters off to far away family and friends with your love, and perhaps a gift or two… the real gift, of course, being that your thoughts are with them, even when you cannot be. For those that do not celebrate the holiday of Christmas, we say the same endearments hold true… enjoy the winter season with your immediate family, decorate however you choose, drink warm hot toddies and allow the candlelight to spark your creativity. Whatever you do… don’t allow yourself to forget the main take-away of A Christmas Carol. Be caring, giving, and loving to all of those around you, value their lives as you value your own. Only then will you truly find the spirit of Christmas inside of you!

Safe and Happy Holidays to All